20

BCD SPECIAL REPORT ON

HERITAGE RETROFIT

FIRST ANNUAL EDITION

cooler, potentially inviting interstitial

condensation. When combined with a

decrease in air movement due to draft

exclusion, there is a real risk that dry

exterior walls above ground floor level

could become damp. Proposals for the

retrofit were therefore preceded by a

three-year programme of investigation,

monitoring and modelling to develop

a clear picture of the hygrothermal

performance of the spaces and fabric that

could be most affected, and to provide

a benchmark for assessing subsequent

performance, from one season to another.

A modified form of WUFI software

was used by building physics engineers

Max Fordham to explore how the

materials would be affected. WUFI (an

acronym of

wärme und feuchte instationär

– heat and moisture transiency) tends to

underestimate the thermal performance

of traditional materials. Old bricks,

for example, tend to be less well fired

than modern ones and the clays are less

uniform so they do not conduct heat

as well. Nevertheless, WUFI provides a

useful model for assessing the relative

performance of insulation measures and

the effects of cold bridging, particularly

when combined with real data from

monitoring the performance of the existing

structures, and by material analysis.

Samples of brick, stone and render were

therefore sent for testing by Glasgow

Caledonian University, and probes were

installed by Archimetrics in 2011 to

record real time variations in moisture

and temperature at four depths through

walls of different orientation and material.

A weather station was also installed so

the WUFI model could be calibrated

according to the local environmental

conditions and the U-values of the walls

recorded by Archimetrics.

In addition to the technical impact

on the performance of historic fabric, the

insulation of walls and windows has a

substantial design impact, and all aspects

of the retrofit would affect the historic and

architectural significance of the building.

Before any proposals were put forward,

the building was thoroughly surveyed by

the architects and Beacon Planning to

identify how the building had evolved,

what alterations had been made in the

past, and what fabric was original. At New

Court, exterior insulation was clearly out

of the question. Interiors, on the other

hand, were generally quite plain and had

been affected by alterations over the

course of 185 years of student occupation,

particularly in the 1970s when extensive

repairs were required for dry rot.

From a design perspective, phenolic

foam insulation offers the least intrusive

solution as it gives the highest insulation

levels for the least thickness, but the

material is impermeable. The WUFI

modelling indicated that this could

cause problems on those elevations most

exposed to driving rain, and a permeable

solution which allowed evaporation from

both interior and exterior surfaces would

be necessary, particularly on north- and

west-facing walls. The exception was

in rooms where high levels of humidity

would be expected, such as bathrooms.

The solution was to locate en suite showers

and bathrooms away from external walls

and ventilate them thoroughly. Only two

bathrooms could not easily be moved. In

these cases the design of the ventilation

was particularly important to ensure that

the interior vapour pressure remains

within acceptable levels, and moisture

levels in these walls will be monitored

carefully for years to come.

INTERIOR WALL INSULATION

Most rooms had been subjected to

extensive repairs in the past, particularly

the exterior walls, due to defective

gutters and outbreaks of dry rot. Few

retained original plasterwork. The

exterior walls were stripped of their

plaster finishes and refinished with a

lime plaster base coat to ensure that all

gaps were sealed, particularly where

penetrated by structural timbers and

joinery. As well as being essential for

air-tightness, this would also help to

draw moisture away from joist ends

and other vulnerable timbers. The

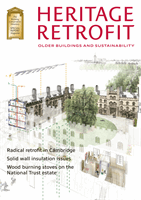

Originally the façades facing the courtyard were all rendered with Roman cement, later repairs were executed in

cement, and they have now been re-rendered using a more permeable hydraulic lime painted with limewash (above).

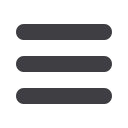

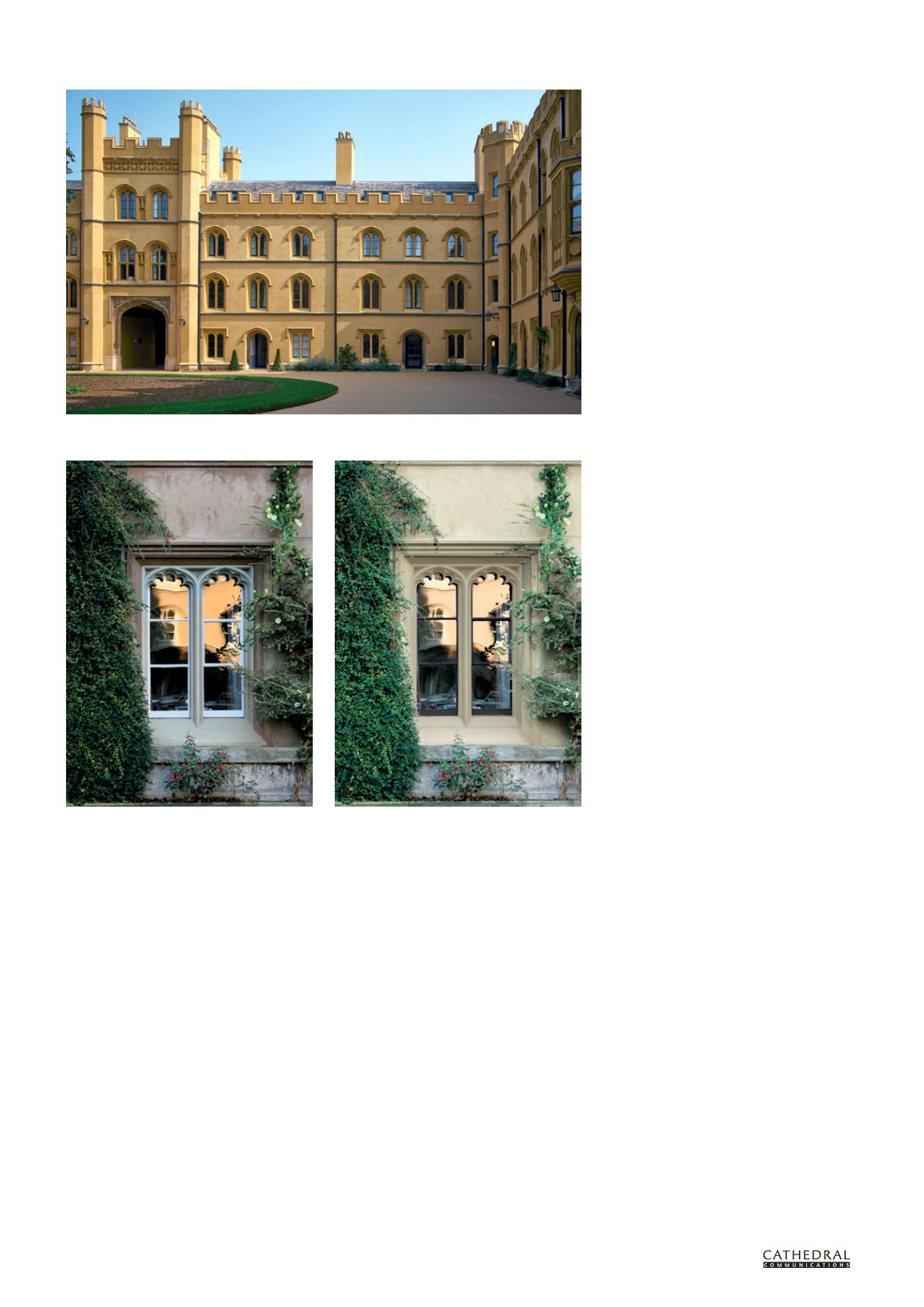

One of the windows facing the courtyard (left) at the start of the project, and (right), the same image modified

to show the architect’s proposals for re-colouring the walls and window frames, following surviving evidence of

the original colour scheme (All photos: Tim Soar)