Disability Access Provisions for Historic Buildings

Robin Kent

|

|

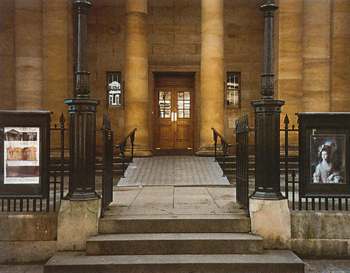

| Access Ramp, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh: a stone ramp to the main entrance from the pavement and the road, adjacent to cobbled and pebbled car park spaces which can be used by disabled patrons. The ramp was designed by Simpson and Brown Architects. (Geoffrey Lord, ADAPT) |

From 1st October 2004, owners of some historic buildings are compelled by law to carry out alterations to make their buildings accessible to disabled people.

Historic buildings which have been extended or which have undergone a change of use may already have the ramps and toilets defined in Part M of the Building Regulations or the Technical Standards (Scotland). Some historic building owners also provide large print and Braille user information, tactile displays, induction loops or infra red sound enhancement. But further improvements may still be required under the Disability Discrimination Act 1995 (DDA).

Since 1999 Part III of the Act has required all 'service providers', including owners and tenants of listed buildings and scheduled monuments open to the public, churches and employers with more than 15 employees, to provide information and assistance for disabled persons. By 1st October 2004 they will be additionally required to carry out 'reasonable adjustments' to physical features of their buildings. The Disability Rights Commission has recently announced that the duty will be extended to include all employers and, by 1 September 2005, the Secondary Education Needs and Disability Act 2001 (SENDA) will also include owners and tenants of historic buildings used for higher education, such as universities.

The DDA includes a wide-ranging definition of disability as: 'physical or mental impairments which have a substantial and long term (12 months or more) adverse effect on a person's ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities'. In addition to wheelchair users and ambulant disabled persons, this definition includes those with poor manual co-ordination or little strength, for example those who are unable to turn knobs; those with sensory impairments, including impaired sight and hearing; and those who lack memory, concentration or understanding. Many more people who are not disabled experience such effects on a temporary basis, including pregnant women, children, elderly persons and those who are emotionally disturbed.

Access for everyone to historic buildings open to the public may be desirable but this was not always appreciated by the original builders. Castles, for example, usually discourage access for all. Improved access can, however, considerably increase visitor numbers and hence income to historic properties by making the built heritage more attractive to as much as 40 per cent of the population.

PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT: THE ACCESS AUDIT

Ideally the first step in improving access to a historic building is to commission an access consultant to carry out an audit of the whole building. Members of the National Register of Access Consultants or other professionals with appropriate qualifications and experience should be used. Local authority access officers and disability organisations may also assist and some may also offer grants. Local user groups representing a range of disabilities should be invited to participate and contribute to the report. Some historic building owners may also wish to host disability awareness training sessions to help staff appreciate the attitudes and problems of disabled users.

For many historic buildings, entrance steps and the lack of wheelchair-accessible toilets may seem to be the only problems but circulation within the building and escape from it should also be considered. Signs, lighting and sound systems and even decorative schemes should be considered. Only five per cent of Britain's one million visually impaired people are completely blind and many can be helped by the use of colour schemes with subtly contrasting tones, compatible with historic interiors. There may be other problems which should be identified from the start to ensure that effort is not wasted on what is obvious only to find that, for example, wheelchair users cannot negotiate the entrance lobby, or reach the ticket counter.

The aim is to achieve independent access for most disabled people, without assistance, and the audit should identify where the building falls short of this aim and exactly why. It should also suggest possible solutions and priorities. It should be based on BS8300:2001 although even this is not fully comprehensive and needs to be supplemented by RNIB and other standards, reflecting the fast developing field of access studies. Tick-box checklists seldom provide the level of detail required and are quickly outdated.

MAKING THE NECESSARY ALTERATIONS

After the access audit has been carried out, decisions need to be taken either to remove obstructions, to alter them, avoid them, or provide reasonable alternative provisions. Special care is needed to ensure that the valuable features of historic buildings are not damaged and where alterations are being contemplated it may be necessary to employ a conservation architect to assess the 'conservation barriers' to access and advise on detailed design.

Access solutions should neither marginalise nor overstate disabled persons' needs. For example, if it is not possible for disabled people to use the main entrance, the new entrance should be as close possible to it, so that the dignity of disabled people is not harmed. The main entrance should be adapted in preference to a side or rear entrance. It is also important that the access point is available to all, not exclusive to disabled users. Similarly new accessible toilets should, be sited in proximity to standard toilets, if possible and they should be unisex to enable carers of the opposite sex to accompany users. Ideally these should not double as baby changing facilities, since this regularly renders them unavailable to disabled people.

|

|

| Access Ramp, National Gallery of Scotland: main entrance front steps and a metal ramp linked to a side ramp (Geoffrey Lord, ADAPT) |

Short ramps should not exceed a gradient of 1:12, but 1:15 or less is preferred for ramps longer than about 2 metres. Where possible, ramps to entrances should respect the symmetry of existing elevations and not leave them with a lop-sided appearance. Steps should always be provided as well, since they can be easier for ambulant disabled people and those with visual impairments. Curved ramps can sometimes appear more 'natural' and less obtrusive and they should take advantage of existing slopes and planting to help them blend in. New walls should be constructed with materials which harmonise with the existing walls.

Ramps and steps should include suitable surface finishes and lighting provisions; steps should have contrasting nosings (ugly yellow and black stripes are not necessary) and wide treads. Ground surface treatments are of great importance for accessibility and surfaces which are hard to walk on or which impede wheelchairs should be avoided. For example, slip resistant hard surfaces such as brick or stone paving are more suitable than gravel, chippings, setts and cobbles. Similarly, rubber doormats are more suitable than coir, while shallow dense pile carpets, polished floorboards, wood blocks or tiles are easier for wheelchair users to negotiate than deep pile carpets.

Handrails are required for two or more steps and at least one handrail should be provided for ramps more than two metres long. Where possible these should be designed to replicate or harmonise with any existing examples. If adequate records survive, it may even be possible to restore original railing designs. The handrail itself should not be greater than 50mm wide and here again, it may be possible to employ traditional sections.

Moveable ramps may be a temporary expedient but where historic buildings are concerned, they should only be considered as a long term solution if all other options have been exhausted. For historic buildings the principle of 'reversibility' (the use of alterations which can be removed or reversed without permanent effect) should not be used as an excuse for a low standard of work that detracts from the quality and setting of the historic building.

If the front of an historic building cannot be reconciled with ramps or handrails, it may be possible to form a ramp inside the main entrance or use a side or rear entrance. The proximity of the designated blue badge parking bays and setting down points should be carefully considered and clear signposting provided to any alternative entrance. If ramps cannot be provided [deleted text: without great disruption or cost], stair or platform lifts can be used. Because they are often quite bulky and require fixing to masonry, these may not be acceptable on the fronts of historic buildings, but can be useful internally, if carefully designed, and in spaces of less historic value. The requirement for suitable emergency escape provisions for users should however be kept in mind and Fire and Building Control officers consulted.

At present, forming ramps and providing toilets for disabled persons is zero-rated for VAT purposes for charities (including churches) and residential premises, and may be similarly zero-rated for some other historic buildings.

PLANNING PERMISSION AND STATUTORY CONSENTS

It should be remembered that the DDA is primarily concerned with service provision and only requires 'reasonable' adjustments to buildings. The Government wishes this to be defined by case law but the DRC Code of Practice offers a range of criteria for assessing whether physical adjustments are likely to be reasonable, including the nature of the service provided and resources available, the effectiveness, practicality, cost and disruption of the proposed adjustments.

The DDA does not override the need for planning permission, conservation area, listed building and/or scheduled monument consent, so that it may not be possible to improve access to some parts of some historic buildings. A measure of compromise, what PPG15 calls 'a flexible and pragmatic approach', is recommended to preserve historic value and significance. Relaxations of the building regulations may be needed and here, too, the recognition, in BS 7913, that not all standards can be applied to historic buildings will help.

If disability access provisions are treated as additions which respect existing historic fabric, rather than alterations, and skilfully integrated, they need have no more effect on historic buildings than sympathetically designed modern services, health and safety or fire precautions. Hopefully, most historic building owners concerned will recognise the considerable advantages of meeting the widest range of access needs possible, and have access provisions in place before they are faced with any possibility of compulsion.

~~~

Note

This brief summary is not a comprehensive guide to the law or specification, each historic building will need separate consideration.

Recommended Reading

- British Standards Institution, BS 8300:2001 Design of buildings and their approaches to meet the needs of disabled people

- DRC, The Disability Discrimination Act 1995: Code of Practice: Rights of Access, Goods, Facilities, Services and Premises, Feb 2002

- Easy Access to Historic Properties, English Heritage, 1995

- L Foster, Access to the Historic Environment: Meeting the Needs of Disabled People, Donhead, Shaftesbury, 1997

- J Penton, 'Accessibility audits', in Architects Journal, 4th December 1997, pp51-54

Further Information

- The National Register of Access Consultants provides list of qualified access consultants available to carry out access audits. Contact the Register Manager on 0207 234 0434. www.nrac.org.uk

- DRC Helpline, for free information about the Act: Tel 08457 622633. www.drc-gb.org

- Through the Roof, for information on access to church buildings: Tel 01372 749955. www.throughtheroof.org

- The

ADAPT Trust for information on access to art galleries: Tel 0141 556 2233

E-mail adapt.trust@virgin.net