All that Glitters

Alexandra Miller

|

| A close up of plasterwork at the London Coliseum: the metallic finish of the shields is indicative of gold leaf, and is easily distinguished from the brassier colour of the entablature above, which is almost certainly bronze paint. (Photo: Alexandra Miller) |

Our love affair with gold and other shiny things has been a long and interesting one. In 2009, the Staffordshire Hoard, the largest discovery of Anglo-Saxon gold ever found in the UK, captured the attention of the international press. It was such an important find, not just because of the quantity of gold found, but because it showed that immensely technical and hugely complex methods had been used to extract inferior metals from recycled gold alloys. When this took place in the 6th century, this extraordinary task would have represented an immense expenditure of precious resources for an end product with no great practical use or value – apart, of course, for the unrivalled symbolism of power and success.

Alongside its use as currency, gold has always been used to adorn the most important religious and royal art, palaces and stately homes, places of worship, mausolea of the rich and powerful, aristocratic attire and fine jewellery. Its preparation from ore to decorative gold leaf and solid bar is such an ancient technique that there is no exact record of when it began, although we know the act of working gold into thin sheets is recorded as far back as ancient Egypt.

The use of gold to honour and serve only the very highest of institutions stayed unchallenged until the advent of electroplating in early 19th century Britain. Originally discovered during the relatively mundane investigations into materials to improve the conductivity of electrical cables, gold plating was put to immediate commercial use.

WHY GOLD?

Chemically speaking, gold is an extraordinary element with many desirable properties. It never tarnishes due to the difficulty oxygen has bonding to its only electron in its outer 6th shell, making any possible chemical bond too weak. This property makes it eternally perfect and is one of the defining reasons it is so highly prized for decoration. It is also highly conductive, even occurring as trace elements in our blood where it helps with conductivity of our heart’s electrical impulses. Gold is non-toxic, which if you know much about the history of most other decorative materials is quite remarkable, and with a melting point of approximately 1,000°C, it has ensured that this material could only be worked by experienced and established goldsmiths, usually with very rich and determined patrons: thus protecting its exclusivity and rarity.

Unfortunately, gold is also incredibly rare. It has been estimated that “all the gold ever mined in the history of the human race would fit into a cube about 60ft on edge” (Theodore Gray, The elements, a visual exploration of every known atom in the universe. p181).

These attributes have led to highly refined craftsmanship, resulting in the use of the thinnest leaves of gold to cover surfaces and maximise coverage. This technology, which dates back thousands of years to the ancient civilisations in Egypt and China, involves melting the gold or gold alloy and pouring it into flat sheets. When cool and hardened, these sheets would then be cut into small squares and hand beaten to flatten out.

|

| Detail showing the use of gold paint in Japanning on a Kelmscott Manor cabinet. (Photo: Alex Schouvaloff by kind permission of the Society of Antiquaries of London) |

Because of gold’s density, the resulting ‘leaves’ of gold still retain their structural integrity at approximately 0.1 micron thick (1/1,000 the thickness of standard printer paper) and can cover a vast area. There is very little physical material in a leaf of gold – most of its value is in the crafting of the leaf. For example, in 1983 just 4.5kg of gold was used to gild the whole roof and all the clock faces of Big Ben (the Elizabeth Tower), an overall surface area of around 18,000 sq ft. Very little can go a very long way.

HOW IS GOLD APPLIED?

The techniques used by gilders to apply gold leaf to surfaces are, in very basic terms, defined primarily by the type of glue needed to stick the gold to a substrate. The two main types are water based and oil based, known individually as water gilding or oil size gilding (there are many other variations). Where gold is to be used in powder form, various synthetic oil varnishes, resins or natural protein based liquids, such as egg white are used to hold the particles of real gold in suspension, forming genuine gold paint.

Regardless of technique, the first step is to apply a waterproof coloured substrate upon which to apply the gold. This is to ensure that the final layer of gold has a solid and even appearance.

WATER GILDING

Simply put, water gilding is the painting on of water mixed with a little gelatin and alcohol, over a carefully prepared ground of gesso (typically chalk bound with animal skin glue) coated with pigmented clay mixed with rabbit skin glue called ‘bole’. The gilding water activates the glue in this substrate to create a sticky layer which the gold leaf will stick to. Once laid, the gold leaf can be burnished to a high shine using an agate stone.

Water-soluble adhesives are generally unsuitable for exterior decoration as the gold leaf is easily damaged by moisture. Water gilding is also not usually found in British interior decoration as it is a very labour intensive process and the high shine would have been found too garish for the prevailing aesthetic of most British decorative periods. However, the technique was widely used on the Continent for furniture and picture frames or as highlights on architectural features such as column capitals, and it may be found in Renaissance and Rococo interiors such as The Palace of Versailles.

OIL SIZE GILDING

|

|||

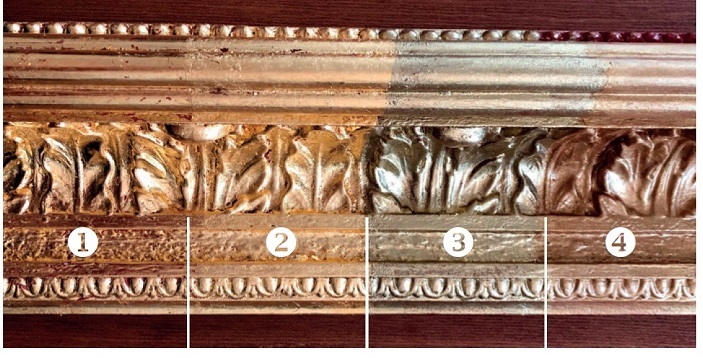

| (1) WATER GILDING with gold leaf laid on a base of clay and glue and once dried, burnished to a high shine | (2) OIL GILDING with gold leaf laid on a base of ‘size’ (glue) and dusted with a soft brush to remove any lose gold, but not burnished | (3) GOLD-POWDER mixed with a medium, in this case, three-hour gold size: it has come out darker due to the resinous medium. Gilders can also dust the powder on dry but this is only advised on areas of light traffic | (4) BRONZE POWDER mixed with a medium, in this case ormaline, a clear cellulose liquid: in isolation it is quite a convincing alternative to gold, but alongside genuine gold the differences are clear |

For external applications and large-scale interior decoration the oil size gilding technique is commonly used. This is similar to water gilding but instead of a waterbased adhesive, a specially prepared oil size is applied directly to the non-porous substrate. This oil size acts like a contact adhesive: the gilder has to wait until it has all but dried out before applying the gold leaf. This requires great skill gained though experience and lots of trial and error. Unlike water gilding – where you can apply immediately to the wetted surface (indeed, a skilled gilder can sometimes ‘aquaplane’ the gold leaf into position and remove any crinkles), oil gilding is unapologetic. Once you place the gold leaf on the oil size, it is stuck fast. You cannot reposition it and you cannot burnish it to a high shine.

POWDERED GOLD PAINT

Gold is one of several metals that are sometimes used in paint form, as will be described in the next section. In this case it is genuine gold leaf that’s ground into a powder and suspended in varnish or other viscous liquids to make gold paste or paint. As the medium is translucent, gold paint is generally applied over an orangey-yellow ground, but there is no additional layer of size to worry about or any further burnishing, so the user is free to apply gold in a more immediate fashion. The gold paint technique is thus a much simpler process which can be picked up quite easily by any novice who can wield a brush, so you may wonder why this technique has not replaced gilding with solid gold leaf. However, there is a catch: painting with gold powder gives quite a different aesthetic result. While gilding will create the effect of a solid layer of an undisturbed gold sheet, gold paint will have a sparkly appearance as each particle of gold will be positioned differently to the next one. As the reflective surfaces are not sitting flat and even, the gold will have a slightly ‘rougher’ surface for the light to bounce off, much like eyeshadow.

In Europe, real gold was not traditionally used in paint form, and to see it being used more frequently, we must look further afield to Asia where sparkle is a desirable feature when used sparingly, such as in Kintsugi – the Japanese art of deliberately highlighting crack repairs with gold paint. As described by Michelle Mackintosh and Steve Wade in Tokyo (2018, p375); “Kintsugi (‘golden repair’) is the repairing of glass, porcelain… and other forms of pottery with urushi lacquer mixed or dusted with gold (powder)…”

This Eastern philosophy of adoration and celebration of the imperfect, known as wabisabi in Japan, is an ancient aesthetic which was not favoured in Western decoration. Indeed, the idea of highlighting and celebrating imperfection with a sparkly and powdery stroke of painted gold seems at odds with the West’s fundamental drive for using gold to highlight perfection, with a perfect shiny sheet of gold. Quite possibly this is the reason why gold was not commonly used as a paint in the West. We certainly had the know-how to make gold into paint and were not shy about using high value commodities as powdered paint pigments such as lapis lazuli, a brilliant-blue mineral which was actually more valuable than gold in the middle ages. No doubt the artists and illuminists of medieval Europe must at some point have considered making life a little ‘easier’ for themselves by grinding up the gold leaf and mixing it in to the oil size. It must have been a conscious decision which came simply down to aesthetic intention, spiritual ritual and demand. In this respect the skill needed to gild played a large part in the value of the finished article.

There is, however, one famous European decorative technique in which genuine gold powder was used as a paint – Japanning. This was an 18th century version of traditional oriental lacquer work adorning timber or papier-mâché furniture which was made in the West for the Western market. Here, gold is used in paint form to imitate the Eastern aesthetic.

FAUX FINISHES AND IMITATION GOLD PAINT

|

| A bronze paint-effect created by Cliveden Conservation for a new statue of Minerva at Pitzhanger Manor and, below, a detail of the finish: this effect was created using modern mica powder in an orangey yellow varnish. (Photos: Alexandra Miller by kind permission of Pitzhanger Manor & Gallery Trust) |

|

Something very interesting happened in the West around the 17th century: faux finishes became popular. If having the genuine article was out of financial reach or impractical, these imitations were the perfect answer, particularly for less wealthy households wanting to emulate the finishes found only in the grandest of households. I say ‘less wealthy’ because it was still hugely expensive and opulent in relative terms to pay an artisan to painstakingly recreate a natural material by hand. However, it was often still a fraction of the cost of having the real thing. Eventually the faux finishes became so popular and the artisans creating them became so good at their craft, that the imitations became as sought after as the real thing – and as demand increased, sometimes just as expensive.

As Ian Bristow explained in Interior House Painting Colours and Technology 1615–1840 (p133); “A considerable part of the housepainter’s skill,… lay in the imitation of various fine materials, especially different varieties of marble and finer cabinet timbers… (as well as) bronze, tortoise-shell and mother-of-pearl”.

Although this article focuses on gold, it is important to put it into the context of the overall interior. The faux finishes (as well as the genuine) were sitting together in grand schemes. Where you would find genuine gold leaf you would also find genuine marble and fine timber, and the same is to be said for faux finishes. There are even examples of faux mother-of-pearl, faux cast bronze and imitation gold brocade fabric being painted directly over genuine gold and silver leaf. It was entirely dependent on the whim and purse strings of the patron.

Metal powders were used to recreate many of these effects because of the unrivalled lustre they offered, that is almost impossible to recreate with pigment alone. The metals used for the faux finishes were chosen because they were far cheaper and more abundant than the real thing. For example, the ‘gold’ powder described in 1764 by Robert Dossie in The Handmaid to the Arts¹ was made from ground up Dutch metal leaf (a thin leaf of copper/ zinc alloy) which came in a variety of golden shades. He also listed several different metals, minerals and other ‘metallic powders’ that could be used on ‘plaister or other busts and figures in order to make them appear as if cast of copper or metals.’

The trouble with almost all of these metal powders is their tenancy to tarnish and dull over time, giving them a muddy brassy appearance. Most modern fine decorators and artists now widely use inert mica powder to give lustre to paint, which does not tarnish. This mineral is so inert and stable that it is widely used in makeup. However, mica has a different kind of lustre to more traditional metal powders as it is finer and the result looks a bit more synthetic. When used as infill for small repairs in original metallic faux finishes, mica tends to stand out, and in this instance it is best to use traditional bronze powder, hand mixed to match the colour of the surrounding finish. However, in applications where there is no older finish to match, mica is preferable and gives very satisfactory results. An excellent example of modern mica powder being used to make metallic paint in place of metal powder is on the faux-bronzed statue of Minerva at Pitzhanger Manor, Ealing.

A common method used historically for creating faux cast bronze was described by Knight and Lacey in The Painters’ and Varnishers’ Pocket Manual in 1825: ‘’For the ground, after it has been rubbed down, take Prussian Blue, verditer and spruce ochre. Grind them separately in water, turpentine or oil according to the nature of the work and mix them in such proportions as are required to produce the colours desired, then grind Dutch Metal in a part of this composition, laying it with judgement on the prominent parts… so as to produce the best effect.’’

Another curious technique from the mid18th century is the use of metal powders mixed into a paint to create the effect of Verdigris patinated copper on doors. It is the replication of patination that often gives faux finishes their lifelike quality.

Generally, because most metallic powders are stable and non-reactive in the short term, they can be bound in oil, making them suitable for painting a vast array of substrates, including timber, plaster, metal, stone, glass and others. However, due to the tendency of most metals to oxidise over a period of time, most metal powders will dull and lose their lustre after a number of years. This is an inevitability and something which is accepted. Because oxidisation accelerates outside, any gold paint found externally will most likely be made with genuine gold powder.

In contrast, there is one mineral pigment which has been revered for its gold-like qualities, orpiment. This was the only bright yellow pigment available pre 15th century (other than the far duller yellow ochre) and is a naturally occurring mineral form of arsenic sulphide. (‘Arsenic’ incidentally comes from the word Zarnikh or Zar, the Persian word for gold.) Its use is almost as far reaching as gold itself; a bag of the powdered pigment was found on the floor of Tutankhamun’s tomb, it adorns the walls of the Taj Mahal and even pops up in the 9th century Book of Kells.

Today, imitation gold paint and other faux finishes are most likely to be found in theatres, cinemas, opera houses and other ‘theatrical’ public buildings such as public houses and even libraries. Often these used cheap lustre powders such as mica to make faux gold paint, mainly as a cost saving exercise as the expense needed to decorate these palatial interiors would have been immense. Faux gold and a variety of other shiny metals and faux finishes were often used in abundance to help create the aesthetic required, be it drama, storytelling or theatrical exuberance and excess. But the glitter and sparkle also served a more practical purpose of bouncing light around the otherwise dark, often windowless interior.

In the words of Shakespeare – ‘All that glisters is not gold.’

Recommended Reading

Ian C Bristow, Interior House Painting Colours and Technology 1615–1840, Paul Mellon Center for Studies in British Art 1996

The Art of Gold Beating (1959) British Pathe: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2Lak64SAaIY

iWonder: Life in colour: the surprising story of paint. Dr Erma Hermens: www.bbc.com/timelines/zqytpv4

Museums and Galleries Commission, Science for Conservators. Volume 1: An introduction to Materials, Taylor & Francis Ltd, 1992: and Science for Conservators. Volume 2: Cleaning, Routledge 2005

1 Cited by Ian C Bristow in Interior House Painting Colours and Technology 1615–1840, p140