Antique Light

Fritz Fryer

|

The Romans introduced fish oil as a fuel for lighting, utilising a fibrous wick in a ceramic or metal 'crusie' lamp, thus superseding animal fat as a medium. This in turn gave rise to the candle. Another Roman innovation was the rush-light, basically an impregnated cord held in the jaws of an iron holder.

The 12th century saw the introduction from the Netherlands of the first decorative light fitting in the baluster form of a solid brass chandelier with its heavy sphere weighted body and 'S'-scroll candle arms, used mainly in churches until the 14th Century when their aesthetic appeal brought them into domestic use in wealthy households.

The effect of the Renaissance was felt in a proliferation of candle burning light fitting designs in both chandeliers and wall sconces, many of which were refined during the 17th century. Notable examples were the Haddon Hall chandelier (c1660) and the Knole House chandelier (c1670). By this time, silver and pewter were favoured materials.

GEORGIAN DEVELOPMENTS

While experiments with gas had been taking place as early as 1688, this fuel as a lighting medium was not harnessed efficiently until the early part of the 19th century.

The great Classical Age gave rise to decorative magnificence in the design of light fittings. Carved wood was popular as it could easily be used to imitate the style of the furniture. The candlestick and candelabra came of age and Robert Adam introduced the most luxurious of crystal chandeliers.

Not until 1784 was there a marked improvement in oil lighting. Aime Argand, a Swiss chemist, patented the Argand lamp in which the wide flat wick was formed into a cylinder around a central tube which allowed air to pass, thus boosting the burning efficiency. A glass chimney placed above created an updraught on the outside of the wick, further enhancing the brilliance of the flame. Heavy colza (vegetable) oil flowed from a reservoir, or font, which was mounted above the level of the burner. This gravity-feed principle was in use until 1859 although the Regency period saw clockwork powered pump lamps integrate the font into the body of the lamp. Thomas Sugg laid the first street gas main in Pall Mall in 1807, bringing gas lighting to the capital for the first time.

VICTORIAN DEVELOPMENTS

Kerosene (paraffin) came into use in 1859. Being a much lighter oil, it could be drawn up a wick, so the font could be situated below the burner. As well as embracing the Argand principle, other developments included the Hinks duplex burner. Each innovation produced a greater light output. Night lights, the squat slow-burning candles, were popular with or without elaborate glassware to shroud them.

Gas lighting efficiency was marred in early Victorian times by both poor gas pressure and the corrosion of the metal burners. In 1858, Sugg patented his invention of the steatite orifice, a ceramic jet, which overcame the corrosion problem and produced more control of the flame. Now glass shades of all descriptions could be used to diffuse the light source.

Not until 1893, with the perfection of the mantle, did gas lighting markedly improve.

Probably the most innovative of Victorian gas fittings was the rise-and-fall gasolier; a device which could be raised closer to the ceiling when not in use, and lowered when light was required in the main part of the room.

EDWARDIAN DEVELOPMENTS

While notable households such as Cragside in Northumberland had electric lighting installed in the latter years of Queen Victoria's reign, illumination of the majority of households where power was available, was essentially an Edwardian phenomenon.

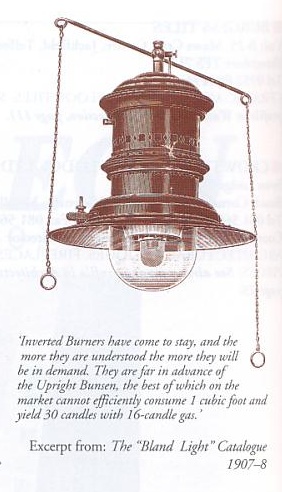

Apart from its increased brilliance, the ability of the electric light bulb to shine downwards at any angle was its great advantage. The gas industry retaliated with the inverted mantle at the turn of the twentieth century, and also with propaganda about the gimmickry of electricity and the injurious rays of electric light.

The flexibility of electric lighting released an explosion of design and manufacture of lamps and fittings on a scale that was totally unprecedented, making light fittings available to all.

|

|

CONSERVATION

While the great majority of antique fittings are preferred converted to, or retained as electric, gas fittings can be adapted for use with North Sea gas or bottled gas by changing the jets in the case of inverted gas mantle type lamps. Mantles are still available. Earlier fittings should have a regulator fitted. It should be stressed that any conversion or restoration work is best carried out by an experienced workshop.

Antique fittings have quadrupled in value over the past ten years, whereas reproduction fittings hold little value and rarely sit comfortably in period settings. However, if matching quantities are required, reproduction is usually the only practical solution. New fittings can be distressed in such a way that they very closely resemble the original.

~~~

Recommended Reading

- Jonathan Bourne and Vanessa Brett, Lighting in the Domestic Interior: Renaissance to Art Nouveau, Sotheby's Publications, London, 1991

- John Griffiths, The Third Man: The Life and Times of William Murdoch, Deutsch, London, 1992

- Josie A Marsden, Popular Collectables: Lamps and Lighting, Guinness Publishing, Enfield, 1990