The Restoration of the Bear Garden, Royal Courts of Justice

Nigel Young

The Bear Garden is one of the principal rooms in London's Royal Courts of Justice. Its splendid Victorian gothic interior is notable for being the only highly decorated space in the building, with richly painted polychromatic decoration and carved ornamentation. However, by the late 1990s extensive deterioration of the wall plaster threatened this striking decorative scheme and a detailed programme of restoration was necessary to prevent further damage. The Royal Courts of Justice were designed by George Edmund Street after he won an architectural competition for the commission in 1866. Construction took 11 years, and the Courts were officially opened amid pomp and ceremony by Queen Victoria on 4 December 1882. Unfortunately, Street did not live to see the completion of his work, having died a year earlier.

Originally known as the Bar Room, anecdotal evidence suggests that the room became known as the Bear Garden because the clamour created by argumentative litigants was reminiscent of the atmosphere at a bear baiting contest. It links the main building to the east block, forming a ceremonial gateway to the inner quadrangle of the Courts. Street's drawings, showing his proposals for the Bar Room, can be viewed at the Public Record Office in Kew.

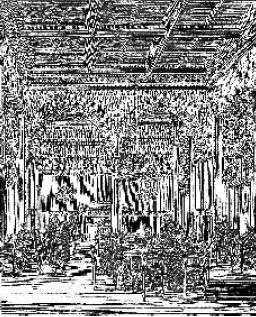

|

| 'The Barrister's Room at the new Royal Courts of Justice' - from London Illustrated News, 6 January 1883 |

The Bear Garden is rectangular in plan and is divided into three bays in the proportions 1:2:1 by simple arcaded walls to the east and west. All of the walls are finished in hard plaster and painted. The upper walls have a solid cream background overpainted with a stencilled ashlar pattern ornamented with fleur de lys. The mid wall area is in red ochre adorned with six large coats of arms. It is separated from the plain green lower walls by a freehand foliate border containing vine leaves, oak leaves and fruit, and the gilded monogram VR at regular intervals. Carved Portland stone was used for the elaborate gilded column capitals and the plain bases, whilst the shafts are in polished red granite. A polished Purbeck stone fireplace with polychrome detail stands at the centre of the west wall.

DETERIORATION OF THE FABRIC

The restoration of the Bear Garden was initiated to prevent the loss of wall plaster and consequent damage to areas of fine stencilled and freehand decoration. The entire area of each flat plastered wall was crazed by an extensive network of irregular hairline cracks and the plaster sounded hollow in varying degrees when tapped, indicating that it was poorly bonded to the brick structure behind. These cracks, which did not occur in the areas of stonework or hard run plaster skirting and architraves, had been present for a number of years, and it was clear from evidence found during the works that attempts had been made to repair the plasterwork during earlier projects.

The cracks were of equal density over the height of the wall and bore no relationship to the painted finish - in fact they were partially filled by some paint layers, indicating that the first occurrence of the problem predated redecoration work. Generally, the wall surfaces appeared to be in a single plane but displacement of the flat surface across the fractured plaster was noted on the eastern wall. The cause of the cracks could not be established conclusively; however, the main contributing factor appeared to be the use of a hard brittle coating over a considerably weaker, friable substrate. This caused stresses to develop in the finished work when any movement occurred, whether due to settlement or thermal expansion and contraction. Whilst it was unfortunate that repairing the plasterwork would involve substantial redecoration of plain painted walls, this would provide an opportunity to reinstate the original Street colour scheme lost during previous works.

THE ORIGINAL SPECIFICATION

In order to establish the materials and methods used in constructing the Bear Garden, Street's original works specification was examined. He described the work as follows: "Brickwork will be sound, hard well burnt square stock bricks from Cowley or Sittingbourne".

Plaster undercoats were specified as lime coarse stuff similar to mortars used by bricklayers but with coarser sand aggregate and reduced mixing times. Bricklaying mortars were specified as follows: "Prepared according to the Patent Selenitic Mortar Company.One bushel of lime is required for six gallons of mortar. The mortar is to be mixed as follows viz throw into the pan of the edge runner two or three pails of water to the first of which 4lbs of plaster of Paris has been added and generally introduce a bushel of fresh grey stone ground lime and continue to grind the whole for three or four minutes until the same becomes a creamy paste and then put five or six bushels of clean sharp sand and then grind the whole for nine or ten minutes longer". The specification goes on to state that plasters are to be ground only for five or six minutes longer, rather than nine or ten minutes The specification goes on to state that plasters are to be ground only for five or six minutes longer, rather than nine or ten minutes.

|

| Stabilising the wall: Core sample showing stabilised plaster; the darker coloured strata at the back of the core is the grout, now filling the void (above); White hatching indicates areas of live plaster, and the white blotches indicate plug positions (below) |

|

The lime is specified as ".best Dorking or Merstham grey stone lime." (both of which are feebly hydraulic when used fresh) and the aggregate as ".sharp coarse clean Thames gravel free from impurities and without any considerable portion of sand.". Finishing coats are specified for walls in the Bear Garden as ".to be plastered with Keen's or Parian cement" and "to be carefully floated and the finished surface to have a fine trowelled plain face prepared for painting.". Applied correctly, both materials provide a superior and durable finish to receive painted decoration.

ANALYSIS OF THE MATERIALS

Investigations on site to confirm the characteristics of background materials and plaster finishes began with the removal of a section of plaster for analysis. This also enabled the background materials to be inspected. This exercise revealed the brickwork to be soft red stock, easily penetrated with a 6mm diameter drill bit. The bricks, which are the same as those used for external facing work, may have been selected for internal wall construction because they were not fully fired, probably owing to lower temperatures towards the edge of the kiln. The plaster undercoats were of a light brown/grey coloured material that appeared to be considerably less hard and dense than the brick backgrounds and was quite dry and friable. Analysis of a sample taken from the wall established that the material was a feebly hydraulic lime and sand mixture in the ratio 1:11.4 by volume. The surface cracking of painted finishes passed through the plaster undercoat. The plaster finishing coat was 4mm thick, pale in colour, extremely hard and dense and securely bonded to the plaster backing coat. Evaluation of the sample revealed that the material was a fairly pure gypsum plaster, the low potassium content tending to rule out both Keenfs and Parian, the patented cements of the time. The results of the analysis suggested that the contractor may not have complied with the architectfs specification during the course of construction work.

PLASTERWORK REPAIRS

It was anticipated that the principal method for consolidating the plaster finishes would be the extensive introduction of hydraulic lime grout between the plaster finish and brick background, to bond the lime undercoat to the brickwork. Specialist contractor Farthing and Gannon was appointed and a trial was set up on site to establish the characteristics required of the grout solution. However, it soon became apparent that this method would not work effectively over the large areas of wall requiring remedial treatment. Firstly, the voids to be filled were considerably tighter than had been expected and, secondly, the dilute ethyl alcohol wetting agent used to encourage the grout to flow freely was immediately drawn into the high suction background and could not be made to run within the void unless introduced in potentially damaging quantities. As a result of this combination, the proprietary lime grout mixture could not be made to flow at all. Another option was necessary and attention became focussed on the adaptation of an earlier attempt to support the plasterwork.

This had involved the use of timber dowels set in the brickwork backing and glued into the plaster surface. Unfortunately, these plugs were rigid and could not absorb the continuing movement in the plasterwork, resulting in radial cracks occurring around the fixings. However, it was thought that a plug that provided both a secure fixing and sufficient resilience to accommodate minor movement might solve the problem. After a number of attempts a suitable material was obtained by combining polyester fibres with hydraulic lime, finely crushed limestone and a solution of water and an acrylic polymer. When cast as 10mm diameter dowels this combination proved resilient yet sufficiently pliable to allow movement in the plasterwork. The plugs were also relatively easy to place.

Holes were drilled through the plaster, 10mm in diameter and 50mm into the brick backing to provide an anchorage for the plugs. The holes were rinsed out with a 10 per cent acrylic solution to reduce suction in the backgrounds and the plugging mixture was forced into the holes using a 10mm diameter wooden dowel. It was accepted that a small proportion of the material would squeeze out into the void behind the plaster, but this was seen to benefit the repair in providing further anchorage for the plug. The location and density of plugs varied according to the pattern of cracks and degree of detachment, but typically they were set at 300mm increments. The effectiveness of the fixings was tested by sounding the plaster. Absence of reverberation indicated the plaster had been made stable.

The

Plaster Fasteners

The plugs used to secure the plaster were designed following careful experimentation to produce a strong fixing with sufficient flexibility to accommodate minor movement. The binder of choice was hydraulic lime NHL 3.5, a material entirely compatible with the existing finishes and which achieves an early initial set. However, in initial trials, the material proved to be brittle when mixed with Portland stone granules and cast as a 10mm diameter dowel, and it tended to rapidly fracture when placed in shear. Although the propensity to fracture was an advantage in reducing tension in the existing plaster, thus limiting the risk of further cracking, it was less satisfactory in providing long term stability to the wall finish. The Portland stone granules were omitted and, to provide flexibility, polyester fibres were added to the mixture along with glass bubbles to improve workability. It was noted that the polyester fibres tended to clump together unless the repair medium was worked for 20 minutes or so to disperse them throughout the mixture.

|

| The restored coat of arms |

The fibre content also proved critical in that too few produced a brittle plug and too many produced a crumbly texture and a tendency for the fibres to bunch during compaction, preventing the plug from being properly inserted. After a number of attempts, a sample peg was produced which was resilient to shear, providing support even when broken, had a degree of pliancy and was relatively easy to place. An acrylic polymer was applied into the anchor holes to control background suction, enabling the water content of the plugs to be reduced to improve compaction and minimize the likelihood of shrinkage during drying.

Grouting

During investigation a limited number of significantly larger

voids were identified for which the peg type repair alone was

considered insufficiently robust. A supplementary method of support

was necessary and the idea of using a thin, purpose-made grout

of hydraulic lime and water which, with the aid of an acrylic

based wetting agent, could be introduced behind fairly large areas

of live plaster was reintroduced. It was accepted that in these

specific areas suction could be reduced by introducing, under

strict controls, relatively large quantities of the acrylic wetting

solution. The particularly dilute grout mix could then be made

to flow in these larger voids. The conservator assessed the void

by tapping, then hydraulic lime was mixed with water to a consistency

considered suitable for the hollow area and introduced using a

large syringe. The lime itself filled smaller voids but also seemed

to combine well with loose aggregate from the render background

to form a fairly competent lime mortar. In both cases, a firm

attachment seemed to be made with background material, as would

be expected with such compatible materials. A further, unexpected,

discovery arising from this method was that the acrylic wetting

solution was also able to combine with loose aggregates within

the void to consolidate fine areas of detachment.

Where appropriate, the grouts were used to consolidate quite large areas, some up to 300mm square. They were also used locally to reinforce the plugs by grouting an area 50mm square around the peg position, then drilling through the spot grout while still green to place the plug. The two repairs were designed to set together as drying occurred, forming a grout-reinforced plug. Since the repair project was completed in September 2001, regular monitoring of the walls has not identified any disruption to the wall surfaces.

THE DECORATIVE FINISHES

Once the plasterwork consolidation was complete, work began to reinstate and, where applicable, conserve painted and clear finishes. The relatively straightforward task of French polishing the oak panelled ceiling was awarded to Chapman Brothers. The existing modern timber ceiling bosses were soon to be made redundant by a new lighting scheme reflecting that shown in historic illustrations of the Bear Garden. These were removed and the resultant scarring repolished to provide a consistent finish. The dry atmosphere created by the modern arrangement had left the timber dry and flat, requiring numerous applications of polish to enrich the wood and enable a bright finish to be achieved.

|

| The restored frieze detail |

The task of assessing the decorative scheme was a more complex one and specialist advice was sought. Lisa Oestreicher Architectural Paint Analysis was commissioned to expose the original solid paint layers on the flat walls and architectural details in order to colour match them. Stencilled decorations were also carefully uncovered, again to colour match but also to establish whether the present patterns followed original ornamentation. Small windows were created in the areas specified for investigation by scraping back finishes with a scalpel blade until the original paint scheme was exposed. The effects of subsequent coatings, atmospheric pollution and changes in the linseed oil over a long period of time had caused the original colours to darken. Evidence was also found of yellowing and darkening of some stencilled decoration caused by varnishing during works in the spring of 1997.

The exposed colours were matched using artist's acrylic paints and adjusted to reflect the scheme before age-induced changes would have occurred. Samples from an arcade arch were removed and mounted in polyester resin, and a cross section was prepared for examination at high magnification. The samples demonstrated that the current colour scheme reflected the original scheme albeit with some variation in tints used. Areas of ashlar block stencilling were taken back to expose layers beneath, revealing that two earlier schemes bearing the same design as the existing had been covered by subsequent schemes. The colours in both instances were well represented by the existing decoration.

Hare & Humphreys were appointed to carry out the repainting and restoration of the Bear Garden. As specialists in this field, their experience, allied to the specialist report, was considered important to ensure the correct approach to the works. The areas to be redecorated were carefully matched to the swatches produced by Lisa Oestreicher and fine tuned to ensure coherence of the tints used over the entire wall area. Larger windows of painted decoration were scraped back where doubts existed regarding the layout of the decoration. Where variations were revealed these were principally in the geometry rather than the actual pattern, and the earliest scheme was reinstated. The finely carved column capitals were cleaned and water gilded after it was discovered that original gilding had been over-painted with gold paint. The finest elements of decoration, the coats of arms and stencilled friezes, were not redecorated but thoroughly cleaned and given a protective coating of water based varnish. It was observed that earlier renovations had interpreted, rather than reinstated, the elegant design by Street. These components are to be restored at a future date.