Bridge Chapels

Edward Green

|

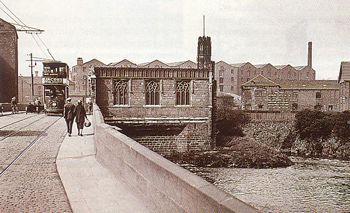

| Wakefield

Chantry Chapel in the 1920s |

|

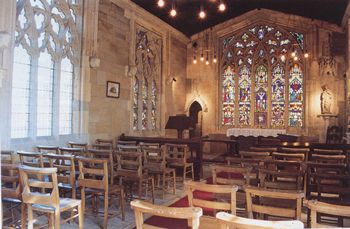

| The interior of Wakefield Chantry Chapel on the Bridge. The stained glass windows date from the 1848 restoration. (A P Oldroyd) |

Chapels were occasionally built on bridges to be available for the spiritual needs of travellers, who would give thanks for safe arrival in a town after a long and difficult journey. During the Middle Ages, bridge chapels were not uncommon and could be found at such places as Leeds, Bristol and of course there was the chapel dedicated to St Thomas Becket on the old London Bridge. Today however, there are only six such chapels remaining in England. These are at Bradford-on-Avon, St Ives (Cambridgeshire), Rotherham, Wakefield, Derby and Rochester – although the latter two chapels are situated on the riverbank and are not structurally part of their bridges.

In addition to the spiritual needs fulfilled by bridge chapels, some (such as the bridge at Wakefield) performed a more practical role, strengthening the structure of the bridge itself. Before the Reformation, bridge chapels were chantry chapels, so called because each chapel was served by its own priest or priests whose duty was to chant masses or dirges for the souls of the dead. According to George Henry Cook, in Mediaeval Chantries and Chantry Chapels, ‘masses were sung for the well-being of travellers and for the souls of the victims of highway violence.’ The priests also assisted the parish priest in services and other work when called upon. Many cathedrals and large parish churches also contained a chantry chapel.

The 1547 Act of Dissolution of the Colleges and Chantries, pensioned off the priests and left the chapels redundant. Many chantry chapels rapidly fell into decay and most were eventually lost. Some bridge chapels survived however, purely for pragmatic reasons – they ensured stability as a structural part of their bridges, taking on a variety of secular uses. Surprisingly perhaps, it is the industrial part of Yorkshire that is fortunate enough to have two of the surviving bridge chapels: one at Rotherham, the other at Wakefield on a bridge over the River Calder.

WAKEFIELD

- THE OLDEST

Wakefield’s

Chantry Chapel of St Mary the Virgin is the oldest and most elaborate.

Situated just south of the city on the nine arch bridge over the River

Calder, the chapel’s history dates back over 650 years. It is an unusual

sight – a tranquil historic oasis so close to heavy traffic and some brick

and concrete architectural monstrosities of the 20th century. At 320 feet

in length, the bridge is unusually long for its age.

It was built by the people of Wakefield, replacing an earlier wooden structure and dates from between 1342 and 1356, the date when the chapel was licensed. Tolls were levied from 1342 with the authority of the Crown, on those crossing the Calder. The funds provided were used to construct a new bridge (this time of stone) of which the chapel itself is a key structural element, built on a tiny island in the volatile river. Building work was probably delayed by the Black Death in 1349–50, which wiped out over a third of the population, including the Vicar, Thomas de Drayton.

The chapel’s stonework was richly carved by skilful medieval craftsmen, particularly on the west front of the building, which was divided into five panels containing depictions of the Annunciation, the Nativity, the Resurrection, Ascension and the Coronation of the Virgin. Beneath the depictions were five arches, three had doorways the other two were filled with tracery resembling blank windows.

In the north east corner of the building is a winding staircase leading to the roof and small bell tower, an embattled turret. This staircase also descends to the small crypt in the wedge shaped base of the building. There are seven windows with fine tracery.

The chapel continued to be used for worship until the date of the Dissolution of the colleges and chantries during the Reformation. Each of the two priests attached to the chapel received a substantial annual pension of £5. At the Dissolution chapels could be acquired by local individuals and the bridge chapel was sold to the Saviles. Wakefield’s three other chantry chapels closed too, and had all been demolished by the early 19th century. But the lovely bridge chapel building survived for practical reasons, as it acted as a major support for the long and narrow bridge.

For the ensuing 300 years, the former chapel was put to a variety of secular uses, including that of a warehouse, library, corn factor’s office and even a cheese cake shop. At one point it was used to store water, which was carried by carts into the town. The bridge was widened in 1758 and again in 1797. Its oldest part is therefore the pointed arches adjoining the chapel. The structure fascinated travellers and was widely painted by artists in the 18th and early 19th centuries, including Turner who produced a watercolour of the building in 1793.

The modern phase of the bridge chapel’s long history began in 1842 when the Vicar of Wakefield, the Rev’d Samuel Sharp secured the building’s transfer to the Church of England and led moves for its restoration. Sharp persuaded the newly formed Yorkshire Architectural Society to undertake its restoration. The Society, founded in the wake of the Oxford Movement, was anxious to restore medieval ecclesiastical remains. Architectural designs for this purpose were put forward during the following year and those suggested by George Gilbert Scott were adopted.

A massive programme of over-restoration was carried out at a cost of approximately £2,500, resulting in the complete reconstruction of the chapel above the pavement level. Approximately £1,700 was raised from donations. The new west facade was slightly different from its medieval predecessor, in that the fifth panel now depicted the Descent of the Holy Ghost, instead of the Coronation of the Virgin. New windows with beautiful tracery were provided. It was originally intended that all of these windows should contain stained glass, but the money ran out and the Rev’d Sharp had to pay a good deal out of his own pocket. Only the east window, two windows on the south and one on the north have stained glass.

Unfortunately, Scott made two terrible blunders during the reconstruction of the chapel. Firstly, he had been persuaded by a local stone carver not to repair the worn and decayed centuries-old west front, but to completely replace it. The original richly carved medieval facade became separated from chapel, finding a new home at Kettlethorpe Hall three miles south of Wakefield. Here it became the frontage to a folly boathouse on an artificial lake.

Scott’s second blunder was in his choice of building material. The new facade was carved from soft Caen stone, which soon crumbled in the city’s industrial atmosphere. Local historian, the late Harold Speak, a former headmaster of the Cathedral School at Wakefield remembered how a heavy storm would deposit a thick layer of sand on the pavement. The facade had to be completely replaced less than a hundred years after Scott’s restoration, this time in gritstone. The work was undertaken by the well known ecclesiastical architect Sir Charles Nicholson in 1939.

The chapel was reopened for Anglican worship on Easter Sunday 22nd April 1848. It was used for the first few years as the parish church of the newly-formed ecclesiastical district of St Mary. When St Mary’s new church was built in 1854 the bridge chapel became a chapel-of-ease, but was more of a liability than an asset to the poverty-stricken parish. Services were held somewhat irregularly and for substantial periods of time it was closed altogether. At the turn of the 20th century the bridge and chapel survived a controversial proposal to completely reconstruct the bridge slightly downstream, as it was deemed inadequate to carry the proposed electric tram system. The bridge carried the only road out of Wakefield to Barnsley and Doncaster until 1933, when a modern road bridge was constructed alongside it, slightly upstream.

Slum clearance led to the merger of St Mary’s with neighbouring St Andrew’s, Eastmoor in the 1960s and for 20 years this over-burdened new parish struggled with the chantry chapel’s costly upkeep. By the late 1980s its future looked uncertain and it seemed likely that the chapel would be declared redundant by the Church of England. The chapel’s long term survival was assured however in 1991 with the formation of a new body of Friends whose immediate task was to raise funds to repair the chapel roof and re-point some of the stonework. The Friends of Wakefield Chantry Chapel was formed mainly by members of the Wakefield Historical Society, Wakefield Civic Society and members St Andrew’s Parish Church.

Over the past decade an extensive programme of conservation work has been carried out for the Friends with the approval of English Heritage. This work included roof repairs, re-wiring and the installation of some very effective new heating. The re-wiring of the chapel incorporated specially designed lighting features, which emphasise the major features of the interior including the communion table, doorway to the crypt and niche.

The most significant repairs and renewal took place to the external stonework of the building in a £30,000 project by William Anelay Ltd. As part of this restoration work, six new carved stone heads (label stops) were provided on the south side of the building, where the old heads were too eroded to conserve. Following the suggestion of architect David Greenwood, the Right Reverend the Lord Bishop of Wakefield, the Lady St Oswald, the Rt Hon Walter Harrison JP and Cannon Bryan Ellis allowed their features to be sculptured by stonemason John Schofield. The fifth head is that of the late Ray Perraudin, a founder of the Friends of Wakefield Chantry Chapel. The sixth is the head of one of Anelay’s workmen.

The Friends of Wakefield Chantry Chapel have gone on to do far more for the beautiful little building and are just £3,000 short of reaching their initial target of £100,000. Most recent work has involved the conservation of the internal stone heads. Their age is unknown. Mixed elements of stone used in the 1840s rebuilding means that they could be of medieval origin. The Friends are now turning their attention to the controversial question of the cleaning of the west facade. In January 2000 a skilful parish boundary change brought the chantry into the care of Wakefield Cathedral at the beginning of the new millennium and relieved St Andrew’s of the burden.

ROTHERHAM – ANOTHER YORKSHIRE GEM

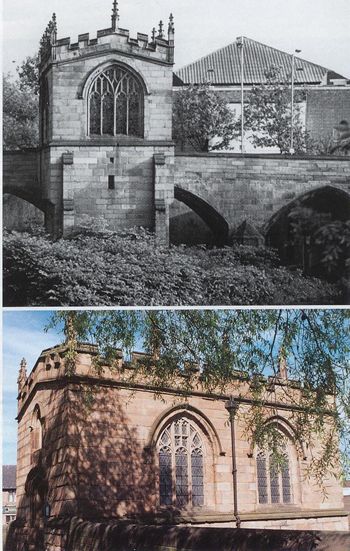

|

| Rotherham Bridge Chapel |

The Chapel of Our Lady at Rotherham dates from 1483 and is situated on the original four-arched bridge over the River Don. The chapel itself was asked for in the will of the master of the grammar school, John Bokyng, who left a small amount towards its fabric. It is possible that Archbishop Thomas Rotherham, Archbishop of York bore the cost of its construction. A light was lit in the chapel every night to guide travellers into the town. It was richly decorated and included a statue of the Virgin and Child ‘of gold, welwrought’.

It existed as a Chantry Chapel for little over 60 years. After its closure under the 1547 Act of Dissolution, the building had a particularly chequered history, serving as almshouses for a time, before being allowed to fall derelict. In 1779 it became the town lock-up or gaol. The crypt was converted into two cells which were beneath the office of the Deputy Constable. Following the completion of a new gaol in the 1820s, the chapel survived as a house and from 1888 it was used as a tobacconist and newsagent’s shop.

The first moves to restore the building as a chapel came in 1901, when almost 1,000 Rotherham residents signed a petition calling for its restoration. In 1913 it was acquired by Sir Charles Stoddart. Restoration was postponed by the First World War, and the chapel was finally dedicated as a place of worship by the Bishop of Sheffield in 1924.

Unlike Wakefield’s chapel, the west front is plain, but there are battlements and elaborate pinnacles. The chapel’s crypt provides a chilling reminder of the 47 years during which it was used as the town’s gaol. The cell doors survive, complete with contemporary graffiti.

Another impressive feature is the East Window, which dates from 1975 and was designed by Alan Younger. It depicts symbols of important events in the chapel’s rich history. These include the coat of arms and letter ‘M’ for Mary Queen of Scots who spent two days in Rotherham on her way to Tetbury in 1569; and heraldic devices for the royalist and parliamentary forces that fought on the bridge during the Civil War in 1643.

THE OUTCOME OF SCOTS FOLLY

|

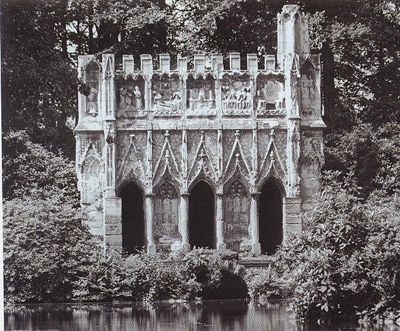

| The original medieval facade of Wakefield Chantry Chapel in 1949, when it formed the frontage of a folly boathouse at Kettlethorpe Hall, two miles south of the city. |

Towards the end of his life Sir George Gilbert Scott came to regret his odd decision to let the beautiful 14th century facade Wakefield Chantry Chapel be sold, remarking that he thought of this ‘in utmost shame and chagrin.’ Indeed he was so anxious to have the front returned to its original position that he offered to contribute towards this objective, if he could persuade enough people to help him. Sadly nothing was done.

The original west facade, described by Pevsner as ‘the most precious of all boathouses’ spent its first 100 years in gentle decline as a romantic folly, a favourite view of Victorian artists and the subject of many early picture postcards. By the late 20th century it was redundant and rapidly falling into decay. Many of the beautifully carved stones had fallen or been pushed into the lake. The nearby Kettlethorpe Hall lay empty for many years and schemes were put forward to move the chantry front to a less vulnerable location.

A number of ideas were suggested, ranging from reconstructing the frontage inside Wakefield Cathedral to placing it in a proposed extension to the city’s main indoor shopping centre. Alas, none of the many suggestions for removal and conservation came to fruition, despite a highly vocalised campaign by Wakefield Historical Society.

In September 1995, time finally ran out for the boathouse. This lovely 14th century facade, which had survived the Reformation, the Civil War and centuries of Yorkshire weather was reduced to a heart-breaking pile of rubble by mindless vandals.

The ruined architectural fragments have since been collected and placed into storage by Wakefield Metropolitan District Council. An estimated 80 per cent of the stonework survives. It is hoped that the facade can be reconstructed in the proximity of the bridge, as part of the Wakefield Waterfront Project, so that visitors will be able to compare the remainder of the original frontage with its 1930s equivalent.

Recommended Reading

Rotherham Churches Tourism Initiative

c/o Rotherham Parish Church, All Saints’ Square, Rotherham S60 1PW

Rotherham Unofficial Website:

www.rotherhamunofficial.co.uk

--------------------------------------------------

Friends of Wakefield Chantry Chapel

19 Pinder’s Grove, Wakefield WF1 4AH

Unofficial Wakefield Chantry

Chapel Website:

www.chantrychapel.org.uk

Wakefield Waterfront Project:

www.wakefield.gov.co.uk