Are Britain's Synagogues at Risk?

Sharman Kadish

|

|

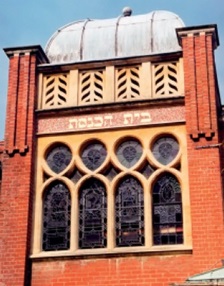

| Middle Street Synagogue, Brighton (1874-75, Grade II*) (Photo: N Corrie/Historic England) |

The significance of Britain’s historic synagogues extends far beyond the small size of the Jewish community, which today numbers fewer than 300,000 – barely a half of one per cent of the total population – with fewer than 40 listed in-use places of worship.

In total, 134 synagogues were surveyed for eventual inclusion in the 2015 edition of Jewish Heritage in Britain and Ireland: An Architectural Guide. These included mainly purpose-built synagogues, both former and functioning, built between the so-called ‘Readmission’ of the Jews under Cromwell in 1656 and the second world war.

London has always been home to about two-thirds of British Jewry and therefore to the majority of synagogues. The beautiful Grade I listed Bevis Marks Synagogue is the oldest synagogue in the UK and has been in continuous use since it was opened in 1701, a reminder that Judaism is Britain’s oldest non-Christian minority faith.

Bevis Marks is located on the eastern fringes of the City of London (where Jews were barred from owning real estate) in the historic heartland of Anglo-Jewry, Aldgate and Houndsditch. The London Jewish community reached its zenith in the 1900s, thanks to the mass migration of around 100,000 refugees fleeing persecution in the Tsarist Russian empire and other parts of eastern Europe. They spread out into the East End, through Whitechapel, Stepney and Mile End, in proximity to the London Docks, a natural point of arrival.

Beyond the capital, the most complete and functioning Georgian and/or Regency synagogues which survive are clustered in seaports and market towns strung out across southern England. These include Plymouth (1761-62), Exeter (1763-64), Cheltenham (WH Knight, 1837-39) and Ramsgate (David Mocatta, 1831-33), all of which are Grade II* listed. Provincial synagogues built in this period share features in common with non-conformist meetinghouses, Jews occupying a position of legal disability analogous to that of Protestant dissenters (and indeed Catholics) before emancipation in the mid-19th century. Their synagogues were discreetly sited and simply styled in a classical idiom.

In France, after the 1789 Revolution and, more fitfully, in Germany during the course of the 19th century, the acquisition of civil and political rights led to the emergence of the Jewish community ‘out of the ghetto’ into the modern world. In 1858 Lionel de Rothschild finally won his long battle to sit in the British parliament as a professing Jew. This was a symbolic moment.

Newly found Jewish confidence in Britain expressed itself architecturally in the emergence of the synagogue as a public building on city centre sites, especially after 1850. The Jewish ‘merchant princes’ of the Industrial Revolution built the first generation of monumental ‘cathedral synagogues’ in the expanding cities of the midlands and north. (They were cathedral-like in scale rather than in order of importance – in the Jewish tradition there is no concept of a hierarchy of synagogues comparable with cathedrals and parish churches.) Of these, only the oldest, Birmingham’s Singers Hill (Henry Yeoville Thomason, 1855-56, Grade II*), has survived intact.

|

||

| Blackpool Synagogue (1914-16, Grade II) (Photo: A Petersen/Jewish Heritage UK) |

It was not until the second half of the 19th century that Jews entered the architectural profession and even then many synagogues continued to be designed by Gentiles. The Victorian era’s ‘Battle of the Styles’ – between advocates of the Gothic and Classical styles of architecture – took on a special meaning in the context of the search for a ‘Jewish’ style of architecture which would be capable of constructing a modern Jewish identity in an open society.

Synagogue architects embraced new materials and technologies and deployed them in an eclectic reinterpretation of traditional styles. Initially, Classicism was favoured, although strict Grecian Revival was never common. Italianate and Romanesque became the most popular styles for synagogues. Canterbury’s Old Synagogue (Hezekiah Marshall, 1847-48, Grade II) is a quirky example of Egyptian Revival that never caught on. In England, Gothic Revival was conspicuous by its almost complete absence; thanks to Pugin, it was regarded as exclusively Christian.

Orientalism was the style that became associated with synagogue architecture all over Europe in the 19th century. The 1870s and 1880s may be called the ‘Golden Age’ of synagogue architecture in High Victorian Britain, when Moorish, Islamic and Assyrian inspired styles, often with paired turrets and sometimes with domes and minarets, made a confident statement indicative of the Jews’ supposedly ‘eastern’ origins.

A rare handful of fine examples, replete with colourful interiors in paint, stencilling and mosaic, have survived in Liverpool, at Princes Road (W & G Audsley, 1872-74, Grade I); London, St Petersburgh Place (George Audsley of Liverpool in association with NS Joseph, 1877-79, Grade I); Brighton, Middle Street (Thomas Lainson, 1874-75, Grade II*); and in Glasgow at Garnethill (John McLeod in association with NS Joseph, 1877-79, Category A).

THREATS AND SUCCESSES

For the first time in many years the 2011 Census showed a slight increase in the Jewish population of the UK (c270,000). The fact remains that the community has fallen from a peak of around 450,000 Jews in the 1950s. Concentration in suburban enclaves in London North, North West and South Hertfordshire and North Manchester (Anglo-Jewry’s ‘second city’), has left Victorian synagogues in historic city centres marooned. Some have succumbed to closure, abandonment and demolition. The battle against redundancy faced by historic synagogues is far more acute than that faced by urban churches because Orthodox Jewish law prohibits travelling on the Sabbath, so synagogues need to be situated within the Jewish neighbourhood and accessible on foot..

|

|

| Bournemouth’s Art Nouveau synagogue (1910-11, unlisted): detail of the tower (Photo: B Bowman/Jewish Heritage UK) |

Jewish Heritage’s latest quinquennial Synagogues at Risk? report (2015) found that all was not bleak for surviving Victorian synagogues. This is thanks to a combination of a high level of listing grade, reflecting their rarity value compared with churches, and the generosity particularly of the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF), which has contributed over £2 million in public grants since 2004

This is not to underestimate the ongoing struggle of maintenance even for those buildings which have received financial aid. Ageing and dwindling regional communities increasingly lack the energy and resources to look after their historic synagogues, for example in Bradford (1880-81, Grade II*) despite HLF funding in 2013, Grimsby (1885-88) and Reading (1900). Coventry’s 1870 synagogue has been sold to a private developer. Grimsby, Reading and Coventry are all Grade II listed and are among the one third of historic synagogues currently deemed at risk.

By and large, concern has shifted to early 20th-century synagogues, especially those dating from the Edwardian era down to the 1930s. The most vulnerable buildings are those which do not enjoy even a basic Grade II level of protection. In the case of Bournemouth’s delightful Art Nouveau synagogue (1910-11), listing was successfully opposed all the way to the top. Its northern seaside equivalent, Blackpool (1914-16, Grade II) was sold to a builder. The subject of a protracted planning dispute, it meanwhile stands redundant and deteriorating. Today, the most threatened synagogues date from the early 20th century and are usually found in northern cities such as Liverpool, Manchester and Sunderland.

The following examples, drawn from the 2015 Synagogues at Risk? report, demonstrate how successful outcomes can be achieved in the contrasting cases of a ‘provincial’ inner-city Victorian synagogue and a 1920s synagogue situated in an affluent metropolitan suburb.

BIRMINGHAM – SINGERS HILL SYNAGOGUE, BLUCHER STREET, GRADE II*

Architectural significance Birmingham boasts the oldest active ‘cathedral synagogue’ in Britain, now over 150 years old. Singers Hill Synagogue was designed by leading municipal architect Henry R Yeoville Thomason in 1855-56. He was also responsible for Birmingham’s Art Gallery and Council House, which has an Italianate banqueting hall that is reminiscent of Singers Hill Synagogue. Singers Hill retains its original and most splendid ornamental gas chandeliers, and possesses figurative stained glass made in the 1960s by Hardman Studios of Birmingham, famed for their association with Pugin.

The challenge Twenty, even ten years ago, Singers Hill was written off by many as having no future. It was situated in a declining inner city postindustrial neighbourhood and was rapidly losing members to the suburban 1960s Central Synagogue in Pershore Road, Edgbaston. Birmingham Jewry has dwindled to about 2,200 people, one third of its former strength.

|

|

| The newly refurbished Singers Hill Synagogue, Birmingham (1855-56, Grade II*) (Photo: Singers Hill Synagogue) |

The solution Today, the immediate vicinity, conveniently situated close to New Street Station, has been regenerated. This is largely thanks to the nearby Mail Box development, the 1960s Royal Mail sorting office, now painted bright red and converted into an attractive complex of shops and restaurants. New apartments have sprung up around the synagogue. Once on the Buildings At Risk Register, the neighbouring Severn Street School, which was the first nonconformist Christian school in Birmingham, has been transformed into the upmarket ‘Scholars’ Gate’ apartment complex.

Meanwhile, contrary to predictions, in 2013 Pershore Road downsized by demolishing its 1960s synagogue and moving into the communal hall. By contrast, Singers Hill, thanks in part to a dynamic young rabbinical couple, has been attracting new members. In the winter of 2014-15 the synagogue’s interior was repaired and completely redecorated almost entirely at the congregation’s own expense. No public funding was involved.

The building was officially rededicated by the Chief Rabbi in March 2015. Thus, Singers Hill Synagogue has regained its position as the flagship of Birmingham’s small Jewish community, an example to be emulated elsewhere.

LONDON – GOLDERS GREEN SYNAGOGUE, 41 DUNSTAN ROAD, NW11, GRADE II

Architectural significance The synagogue’s polite red-brick neo-Georgian facade blends in discreetly with the surrounding suburban houses in a neighbourhood that is still very popular with better-off London Jews. Yet the facade masks the structure’s use of transitional building technology. Digby Solomon’s (of Lewis Solomon & Son) original portion (1920-21) used steel construction but retained the column supports under the gallery, which Ernest Joseph (Messrs Joseph, 1927) afterwards painted black to make less visible.

Joseph’s second phase created a T-shaped, almost cruciform plan and he added the circular ceiling lantern and Portland stone Tuscan porch. The interior features Joseph’s imposing semi-circular pulpit in front of the Ark, flanked by swish, red-veined Sienna marble stairs, and much interesting stained glass.

The challenge When Joseph extended the building through the Ark wall he nearly doubled the capacity to almost 1,000 seats. Prevailing Orthodox preference for small informal worship spaces made Golders Green look old-fashioned. Alternative services held in other rooms on the large site meant that numbers in the main worship space slumped.

The solution In 2007 the neglected synagogue was saved from sale, demolition and replacement with lucrative flats, thanks to a Grade II listing. An English Heritage/Heritage Lottery Fund Repair Grant for the roof followed in 2011. This galvanised the congregation to raise a further £1 million for the repair project.

Some pews have been removed from the rear of the prayer hall and (reversible) partitions installed to sub-divide the space to create a Bet Midrash (small synagogue/ study room), children’s area and function space. The women have been brought downstairs to sit in rows parallel with the long north wall on one side of the Ark. Some issues are yet to be solved, especially regarding the acoustics in the unwieldy vaulted space and defining future uses for the gallery, which is badly in need of redecoration. Nevertheless, the community is to be commended for its courageous bid to render this large synagogue fashionable once again in London’s premier Jewish neighbourhood, one which is increasingly dominated by Hasidic-style shtieblekh (prayer-rooms).

A canny move was the demolition of the two ageing ancillary halls to make way for the new-build Rimon Jewish Primary School. Recent changes in the law linking places in faith schools with ‘church’ attendance have attracted new, young families to join Golders Green Synagogue. The result has been a net increase in membership and, for the first time in many years, a falling age profile.