Maintaining and Repairing Coatings on Cast Iron Structures

Ali Davey and Elaine Troup

|

|

| Detail of the restored Grand Fountain, Fountain Gardens, Paisley |

During the 19th century cast iron became an increasingly popular building material. It was used extensively in the public realm for everything from park benches, post boxes and lamp pillars to tram shelters, bandstands and railway stations.

Outdoor ironwork was generally coated in a lead-based oil paint to protect it from corrosion. This protective coat was also used to add decoration and colour.

Other protective coatings include gold leaf, which was sometimes applied to higher status ironwork to highlight decorative motifs, and zinc galvanising, which was in its infancy in the 19th century. Although not generally considered a historic or appropriate finish for traditional ironwork, rare early examples of galvanised ironwork do exist, such as a Sun Foundry bandstand in Bermuda.

Lacquers were rarely used on outdoor ironwork, although the case study below focusses on an extraordinary 19th-century fountain in Paisley which incorporated oil paints, gold leaf and lacquers as part of the decorative scheme.

Colours for cast ironwork have varied through the decades, influenced by changing fashions and the cost of the pigments used to give paint its colour. The least expensive pigments were used to create what were known as the ‘common colours’. These broadly ranged from off-whites, creams and greys to browns – all of which were applied to ironwork. Other colours, such as various shades of green, dark blues and reds were also used. It wasn’t until the 20th century that pure black and pure white paints became available.

Larger structures such as fountains and bandstands were often polychromatic. Occasionally the paint schemes were highly elaborate, as illustrated by the Paisley fountain. To the modern eye, the scheme looks quite unusual, but contemporary descriptions suggest that the colours used to decorate this fountain in 1868 were typical of that era.

Cast iron was sometimes deliberately painted to imitate another material. Stock cast iron figures, supplied by foundries such as Walter Macfarlane & Co of Glasgow, could be painted to look like bronze or stone if desired.

MAINTENANCE AND REPAIR

Cast iron structures need regular repainting to keep them protected. Following two world wars, the capacity to carry out regular maintenance on many cast iron structures was significantly reduced and many fell out of use. Those which did receive regular maintenance were often painted a uniform colour or in a more contemporary colour scheme.

When it comes to maintaining or restoring these structures and their protective coatings, a strategy needs to be carefully formulated to maximise the long-term performance of new coatings.

As part of the initial assessment, paint samples should be taken from various parts of the structure and analysed by a paint specialist. This can reveal earlier or original colour schemes and will inform the decision to either retain the existing colour scheme or reinstate an earlier colour scheme (usually subject to local planning regulations).

|

|

|

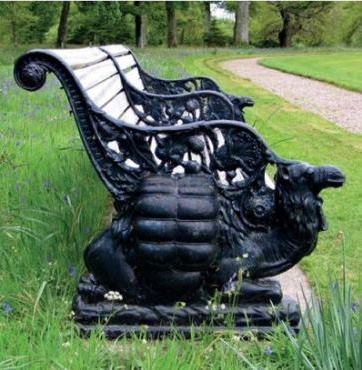

| A mid 19th century cast iron bench at Rothesay, Isle of Bute | Cast iron bus shelter (c1950), Rothesay, Isle of Bute |

Occasionally, structures have been cleaned back to bare metal at some point in their past, but fragments of original paint sometimes survive in sheltered nooks. If existing paint is in relatively good condition, it may be possible to lightly clean areas where the paint remains sound and apply more aggressive cleaning techniques where coatings have failed and corrosion has developed. If the decision is made to clean the ironwork back to bare metal, consider retaining a strip of the earlier coatings in a sheltered location so they are preserved for future generations.

As a general rule, large, more complex cast iron structures usually need a thorough 100-year service. They should preferably be taken apart, cleaned and repainted in a controlled workshop environment which allows hidden surfaces within joints to be cleaned of corrosion. Cleaning and repainting in as dry an environment as possible is essential – trapped moisture in joints or within the cast iron itself can cause fresh paint to fail.

Cleaning large cast iron structures in situ can lead to catastrophic failures of new coatings because corrosion material cannot be cleaned out of joints effectively (painting over them does not prevent corrosion from continuing) and the moisture levels within the iron cannot be controlled before and during the application of fresh paint. If existing coatings are to be removed, adequate measures should be taken to protect against airborne lead from the old paint.

Holes (even small ones) and casting flaws should be filled prior to painting ironwork to avoid corrosion developing in these voids and causing the paint to fail locally. Joints and mating surfaces should be packed with a caulking material to pad the joints, make them watertight and provide a flexible seal that allows for thermal movement within the structure.

Traditionally, red lead paste (a mixture of powdered red lead and linseed/ lime putty) was used for caulking. Red lead powder can still be sourced through traditional boat supply retailers (but requires health and safety precautions when handling). High quality polysulphide mastic is a modern alternative. Whatever filler is used should be compatible with the paint.

If areas of the ironwork were once gilded, there is no substitute for real gold leaf. Gold paints tend to discolour over time due to the effects of UV light, although it is sometimes possible to apply UV-protective coatings to prevent this.

Where paint is being applied to bare metal, current best practice is to use a zinc-based primer with a high zinc content. Traditionally, red lead primer (less toxic than white lead based paints) was used as a primer and is still commercially available. Micaceous iron oxide forms an effective undercoat with normal gloss as a top coat. A variety of specialist systems are available through paint manufacturers with expertise in traditional paints and paints for traditional substrates.

Hard, inflexible paints such as epoxy are not recommended because they are not generally flexible enough to withstand the natural thermal expansion and contraction that occurs in traditional cast ironwork. As a result, epoxy paints can crack over time, drawing in and trapping moisture under the paint layer.

Seek the advice of a historic paint specialist or a paint manufacturer who specialises in historic coatings. Bear in mind that cast iron does not have the same surface or microstructure as steel, so a paint that has been developed for steel will not necessarily provide the best protection for traditional cast iron.

CASE STUDY: GRAND FOUNTAIN, PAISLEY

The Grand Fountain is a 19th-century, Category A listed, cast iron fountain in Paisley’s oldest public park, Fountain Gardens. Gifted to the people of Paisley by wealthy mill owner Thomas Coats of the world famous J&P Coats thread manufacturer, the Grand Fountain is the centrepiece of the park.

The structure is unique as it is the only known example of the pattern No 1 fountain made by George Smith & Co’s Sun Foundry in Glasgow, one of Scotland’s leading iron manufacturers. The unique design of the fountain includes herons, walruses, cherubs and dolphins and is considered to be the best example of a Scottish-made cast iron fountain in the country.

|

|

|

| The Grand Fountain, Fountain Gardens, Paisley, before and after conservation. Inaugurated in 1868, it is the only known example of the pattern No 1 fountain made by George Smith & Co’s Sun Foundry. Re-creating the vibrant original colour scheme designed by Daniel Cottier (1837-1891) was one of the restoration project’s toughest challenges. | ||

The project to restore the fountain was led by Renfrewshire Council with additional funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund and Historic Scotland. The council team was supported by conservation engineer James Mitchell of Industrial Heritage Consulting Ltd and specialist contractors Lost Art Limited.

This complex restoration project could furnish several fascinating case studies but the focus of this article is the re-creation of the original colour scheme designed by Daniel Cottier (1837-1891), an artist and designer born in Glasgow.

Cottier is best known for his fine stained and painted glass work, as well as interior decoration. He worked with architects such as Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson and William Leiper, who in turn often commissioned work from the top ornamental iron-founders of the day, George Smith & Co’s Sun Foundry and Walter MacFarlane’s Saracen Foundry.

Research

The restoration of the fountain took over a year. However, prior to the physical restoration the team had to undertake extensive research into the history of the fountain and its colour scheme. This included referring to the rather frustrating descriptions detailed in the inauguration booklet of 1868:

The decorations of the central fountain, like those of the iron gateways, lamps and railings, are of the richest character. The main fountain is, at the base, toned with deep sombre tints appropriate to iron structures and gradually rises into a series of variegated bronzes that bring out the respective ornamental parts of the structure with additional effect. The base of the foundation, wherever the structure would allow of its appropriate introduction, has had piquancy added to it by small bits of brilliant colouring which take away entirely any feeling of heaviness, and look very pretty.

Consultant conservation engineer James Mitchell took particular interest in finding the right colour, paint and glazing solution for the fountain, given the importance of the original colour scheme. Daniel Lea, production manager with Lost Art, led the restoration works and spent time experimenting to find the best approach to applying the complex coatings. The process was long and arduous and required over 100 paint samples and hours of testing supplemented by an initial paint study carried out by Historic Scotland in 2006.

Restoration

The fountain was dismantled and moved to a conservation workshop, where a long period of repair and preparation of individual pieces was needed before the final coatings could be applied.

Due to the condition of the structure it was essential to clean it back to bare metal. There is much debate about the best way to clean and (equally importantly) seal bared cast iron. In the 19th century new iron castings were often doused with linseed oil while still very hot, which prevented ‘gingering’ or flash rusting before it could be painted. As the paints were then largely linseed oil-based the first coat of red lead suffused nicely with the oiled iron surface. This practice fell out of favour as coatings became more ‘sophisticated’.

|

|

|

|

| Above left: repainting work under way in the conservation workshop. Centre and right: To ensure that the original colour scheme was re-created as accurately as possible, the herons and the tulip to the top of the structure were finished in gold leaf. This should retain its finish for longer than gold paints, which tend to discolour over time due to the effects of UV light. | |||

Today, when coatings are removed by abrasive ‘blasting’ we are exposing the iron in the same way as when it came out of the mould after casting, although it is rarely filled or sealed as effectively or as quickly. The porosity of iron is a result of tiny gas bubbles rising to the surface as the iron cools, leaving a way in for moisture and allowing it to become trapped under subsequent coatings. There are many sophisticated and specialised modern coatings for external use which are formulated for use on steel which, unlike cast iron, does not have any significant porosity issues. Many coatings manufacturers see all ferrous metals as the same, but the key is understanding the complexities of the specific material in question.

Surface preparation

Conservation projects of this nature are rare so the team faced new challenges that resulted in opportunities to develop solutions and improve the process of metal conservation. At the workshop each of the items, many of which had stood saturated for years, was dry-blast cleaned using crushed garnet, a natural mineral widely used as a substitute for silica sand in sand blasting. These components were then placed in a low relative humidity environment, in preparation for coating.

Some light gingering is to be expected due to ambient moisture but it is easily removed. However, in this case, black spots began to erupt after a short time. The spots were magnetite suspended in deoxygenated water and because they reappeared after each attempt to remove them, proper drying was necessary. Items were placed in a custom-made oven to dry over five hours after dry blast cleaning. The worst affected pieces had to be fired up to three times.

Temperature, humidity and timing

Many coatings manufacturers specify a temperature range within which products should be applied but they seldom refer to humidity levels. Treating bare iron in an uncontrolled environment during the British winter has little chance of long-term success. Unless humidity and temperature can be controlled accurately, both in preparation and application, modern coatings are susceptible to failure. On the Grand Fountain project small sections at a time were tightly encapsulated using a proprietary system. The area was blast-cleaned, warmed and dehumidified to the optimum level, then coated. Only in these circumstances will such systems be effective for long periods.

Experimentation and application of coatings, gilding and lacquer

Achieving the effect of Daniel Cottier’s coloured glazes was perhaps the biggest challenge. The colour scheme was based on two main dark, rich colours: a deep red-brown and a dark green. This was lightened by bright, solid colour highlights, gilding and overlaid glazes of bronzed or gold-rich translucent varnishes. This is achieved by adding bronze powder in varying amounts to the first varnish mix.

|

|

| Reassembly of the restored fountain |

The technique of applying bronze and gold in powder form over wet varnish was a skill developed by Lost Art and was varied deliberately on repeat components. The bronzing technique was used on various elements of the fountain but particularly those where reflected light would have an effect, such as on the underside of the bowls. In this case bronze and ‘gold’ dust was blown over a varnished green paint coating repeatedly until the effect was built up. To stay true to the 19th-century approach, no modern equipment was used (other than a pair of healthy lungs).

Research showed that gold leaf had been used to accentuate key parts of the structure. To ensure the vision was re-created as accurately as possible, the herons and the tulip to the top of the structure are today finished in the same way.

THE COATINGS

Following a test assembly of the fountain in the workshop, the individual castings were painted. Different parts of the fountain required different coatings. The pool floor plates, for example, were primed with a 50/50 mix of zinc phosphate and chlorinated rubber then coated with 100 per cent chlorinated rubber to ensure prolonged resistance to water.

The coating solution finally agreed upon for the main body of the fountain was two coats of zinc phosphate primer, one coat of two-pack polyurethane (2 pk PU) undercoat, two or more coats of 2 pk PU gloss and one coat of 2 pk PU varnish, holding the gold or bronze glazes as required, then a final coat of clear 2 pk PU varnish.

This hardwearing coating system can be removed if required and is therefore ‘reversible.’ However, it is vital that it keys well to the (dried) iron and remains flexible during expansion and contraction. This was why such an expensive system was chosen over epoxy paint systems, which are more rigid and therefore arguably much less suitable for cast iron.

TRANSPORT TO SITE AND REASSEMBLY

Great care was taken during packing and transportation to the site to avoid damage. The fountain was pre-assembled in large sections in the workshop prior to transport to site for final assembly. Soft strops were used to tie the castings down to minimise damage to the paintwork.

Castings were then checked on-site for any damage and the final touches were hand painted on site as part of the final assembly process.

Original colours and protective coatings were an intrinsic part of traditional cast iron structures and can tell us much about the technology and aesthetics of the era. It is always worth investigating what lies beneath modern, flaking paint – you never know what you might find.

Further Information

Historic Scotland, Short Guide 4: Maintenance and Repair Techniques for Traditional Cast Iron, Edinburgh, 2013