Two Follies of the National Trust

The Chinese House at Stowe and the Modern Maori House at Clandon Park

Rory Cullen, Nikita Hooper and Christine Sitwell

The National Trust is responsible for the maintenance of around 30,000 buildings across England, Wales and Northern Ireland, including a great variety of garden structures. Amongst these unique buildings are the Chinese House at Stowe Landscaped Gardens in Buckinghamshire which has recently been conserved, and the Maori Meeting House at Clandon Park in Surrey which will be subject to repairs in future.

THE CHINESE HOUSE

|

|

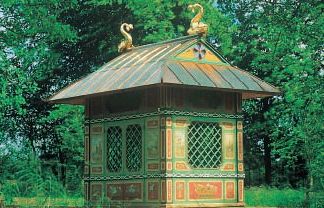

| The Chinese House at Stowe after restoration, with sensitively restored painted surfaces and new finials (Photo: Christine Sitwell) |

The Chinese House is a highly decorative small timber framed structure which can be found in the Pheasantry near the Palladian Bridge at Stowe Landscape Gardens, Buckinghamshire. The first reference to the structure can be found in the archives of the Huntingdon Library in California which dates the building to around 1738, making it the earliest recorded Chinese pavilion in Britain, and a landmark in the rising fashion for ‘chinoiserie’. It is believed to have been designed by the architect and designer William Kent (c1685-1748), who worked on several garden buildings at Stowe during this period.

Various contemporary accounts of the building illustrate its exotic form, as a rectangular structure of small size, which sat on a base held up by piles driven in to the bed of the pond. Access was gained by crossing a footbridge adorned with ‘Chinese’ vases. B Seeley’s engravings reveal two stylised dolphins at either end of the ridgepole, on a gambrel roof. It is believed that the original scheme on the exterior was by Sleter based on the account of 1742 where it is noted: 'it is a square building with four lettices and covered with cloth to preserve the lustre of the paintings: [inside, a statue of] a Chinese lady as if asleep, her hands covered by her gown… the outside of the house is painted in the taste of that nation by Mr Slatea: the inside is japann’d work'. Although none of the original paint survives intact, the attribution of the decoration to Sleter (or ‘Mr Slatea’) is plausible because it is known that he painted scenes in both the Grotto and Stowe House.

The Chinese House did not remain in the gardens of Stowe for long, and it had certainly disappeared by 1751. There is evidence that Richard Grenville, the heir to Stowe, moved it to Wotton House, which he also owned, about 20 miles away. Most probably he wished the grounds at Stowe to follow the classical themes that were adopted throughout the landscape. An account of 1779 records that a pair of painters spent three days each working on the structure. Even here it was moved around, and a 19th century wash drawing shows the pavilion standing on an island in middle of the lake, and later it was moved closer to the main house.

In 1950 the principal house was used as a preparatory school for boys, who often passed their time by adding their own ‘designs’. Its journey continued in 1959 when it was purchased by Major Michael Beaumont and moved to Harristown House, Kildare, Ireland. Here it stayed, with two further moves around the Estate, until its origins were identified by Dr Patrick Conner, provoking interest from the National Trust who had taken over the Stowe Estate in 1989.

In 1992 the owner offered the structure to the Trust following concern over its deteriorating state. Funds for the purchase were raised through grants from the Monument 85 Trust, the Pilgrim Trust and from the Alex Clifton Taylor bequest. An appeal in memory of Gervase Jackson-Stops subsequently collected funds that paid for its complete restoration (1).

So it was that in 1997 the National Trust was able to embark on a major conservation and restoration programme to conserve this unique building.

CONSERVATION

As with many conservation projects undertaken by the Trust, the project involved crossdisciplinary working between conservators, curators and the Building Department. The treatment involved wood and paint conservation disciplines, with the specialists liasing over different aspects of the project to ensure a holistic approach. The structural conservation and restoration would be primarily undertaken by Tankerdale Limited, specialists in the conservation and restoration of historic joinery and furniture, with a contract value of just under £150,000. Bush and Berry undertook the conservation and restoration of the painted surfaces.

|

|

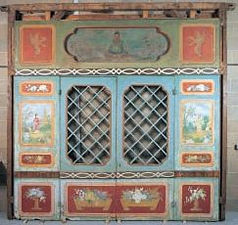

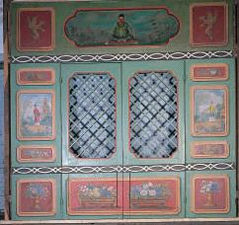

| The north elevation panels in the studio, before and after conservation. The faded top panels (top) were protected from the weathering by the eaves and retain much of their original paintwork, but those below, which appear much brighter in the ‘before’ image, had been repainted several times, most recently quite crudely. Compare the small vase of flowers in the second row on the right, before and after. (Photos: Ian Blantern) | |

|

The Chinese House is constructed of flush-faced panels of softwood applied to both sides of an oak frame. Each of the four sides of the building is an individual unit, joined by pegged mortise and tenon joints at the corner, when assembled. These exposed corner joints are then covered with pilasters constructed from softwood. There are lattice windows to each end and in the double doors of each side. The roof was originally elaborated with a pair of stylised dolphins, one at either end of the ridgepole, but by the time of the restoration all that remained were the two small gablets set into the roof. The approximate dimensions of the structure are 3.8 metres in length by 2.8 metres in width, and 3.4 metres in height.

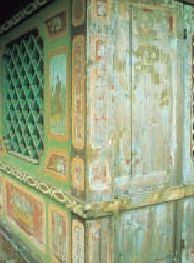

Both the structure of the building and the painted surfaces were in poor condition. The lower sections of the structure and the corner pilasters had suffered from extensive rot and insect infestation and from the splitting and shrinkage of the softwood panels. The use of inappropriate repair materials had led to further damage. The exterior painted surfaces were badly cupped and flaking, and weathering had caused extensive paint loss on two sides of the building. The interior surfaces were in better condition but had been damaged by vandalism and water staining.

The brief for the project had the overarching aim of returning the structure to a decoratively and structurally stable condition to allow it to be safely displayed once again in the landscape of Stowe. It was stipulated that the repairs must be carried out according to established conservation principles: retaining original timbers wherever possible; replacing timbers with those matching the original in species and moisture content, profiled to match the original; and using traditional adhesives. The entire process was to be recorded, in photographs, notes and drawings, at all stages of the work, and on its completion.

The work was carried out in close accordance with these principles. As the work progressed, it became obvious that the attachment between the inner and outer layers of the walls on the longer sides was much less robust than anticipated. The rot damage and old repairs were also more extensive than expected. This in turn led to more dismantling of these sides than originally anticipated. Where sections were rotten, these were treated for rot and woodworm and consolidated with ‘Bencon 20’ epoxy resin after appropriate stabilisation of the painted surfaces.

The majority of pine timber replacements were undertaken with re-used 18th century Baltic pine, of similar grain and moisture content. The new oak sections were generally constructed utilising new English oak, similarly matching grain and moisture content to the original. Joints which had originally been bonded with hot animal glue were treated in the same manner. New splices and patches were joined with ‘West System Epoxy 105’ resin and 205 hardener.

Where nails had been inappropriately used, restricting the movement of the wood, damage had been caused through expansion and contraction. Less harmful methods were introduced to prevent further damage. This was carried out with the use of non-ferrous fixings, softwood buttons and ‘biscuit’ joints (a discreet modern jointing technique in which a proprietary-made oval biscuit of beech is glued into slots cut in each meeting face, like a traditional floating tenon). The majority of the fixings employed were stainless steel screws, counterbored below the surface of the wood and pelleted to cover the heads. Any original nail fastenings which were rusting were replaced with screws as above, or with stainless steel nails, panel and moulding pins, covered with small softwood pellets or diamond shaped patches.

|

|

| A detail of one corner before restoration, showing one of the worst areas of paint loss (Photo: Christine Sitwell) | |

|

|

| A detail of one of the vases of flowers partly scraped back to reveal elements completely lost in the later scheme. Sufficient information was discernible to enable an expert restoration of the original. (Photo:Christine Sitwell) |

To allow for the effects of changeable humidity once the building was re-erected outside, some shrinkage cracks were retained. This would avoid compression of joints as the moisture content of timbers increased and would safeguard the restored decorative finishes. The cracks would be monitored over a year of changing humidity to ascertain how much they should eventually be filled to maintain the necessary room for fluctuations.

The extent of decay in the roof of the building meant that it was impossible to effect a conservation repair, and a decision was therefore taken to construct a new roof to a design by Fraser Brown, an architect from Inskip & Jenkins, in consultation with Tankerdale. It had been intended to retain the gablets, which were believed to be original. However, close examination revealed that they were of questionable date and in poor condition, so exact replicas were created and installed. The new roof, which was framed in oak and clad externally and under the eaves with treated tongued and grooved softwood, was constructed in Tankerdale’s workshop and then transported in sections for re-assembly on site. Fraser Brown also designed a new elm floor, which was made and fitted by Joe Shingfield of the National Trust’s Park Farm Workshops in its Thames and Chilterns Region.

The painted surfaces proved to be an interesting challenge as the existing paint layers on the exterior were in poor condition and on two sides were either partially or wholly missing. Paint analysis and x-rays revealed a history of paint loss and re-decoration, with the existing scheme being a complete alteration of the decorative design. Cleaning tests indicated that the two 20th century restorations could be removed to reveal the underlying 19th century decorative scheme which was relatively intact. Analysis of the interior indicated that the existing scheme was early 19th century so the decision was taken to remove the restorations on the exterior so that the house would present a decorative scheme of the 19th century on the interior and exterior. On the two sides of the house which suffered extensive paint loss, existing paint was cleaned to reveal the 19th century decoration and total losses were recreated based on photographs taken for Country Life in 1949. Although the house had been restored in 1937, the restoration appeared to recreate the 19th century scheme.

A number of synthetic and traditional varnishes were tested for appearance and durability, and after consolidation and cleaning, small losses were re-touched with dry pigments in Paraloid B72, a synthetic resin. Recreations of the missing sections were painted in traditional lead-based oil paint. The use of lead paint as opposed to a modern synthetic paint was chosen on the basis that its visual appearance and ageing characteristics would be more in keeping with the original.

MAINTENANCE

As with any conservation/restoration programme, the protection and maintenance of the structure must be considered. The primary concern for the Chinese House is its exposure to the elements, owing to the inherent fragility of its structure and decoration. To mitigate this, canvas sheeting is suspended under the eaves from new hooks, attached to fixings in the ground. Such sheeting provides a measure of protection against water and frost, and echoes the canvas awnings with which the building was provided in the 18th century. Moisture levels inside the building are controlled to a degree by the provision of new ventilation between panel skins and within the structure. The canvas used externally is also ventilated (2). A yearly inspection of the house is undertaken to record its condition and where necessary to undertake minor conservation treatment.

THE RESULT

Close collaboration between various departments of the National Trust and high standards of conservation repair have ensured that this unique pavilion has been returned to a stable condition reflecting its exotic appearance after numerous journeys in its 266-year history. With appropriate maintenance it should remain in the landscape at Stowe for the enjoyment of everyone for many years to come.

THE MAORI MEETING HOUSE

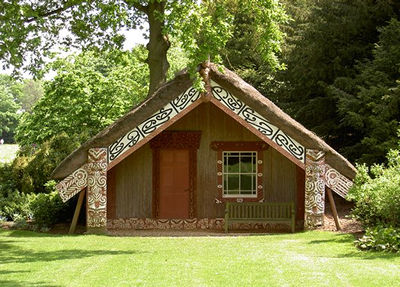

The National Trust has responsibility for another building that has travelled even further during her lifetime: Hinemihi, a Maori meeting house, at Clandon Park in Surrey.

Hinemihi o te Ao Tawhito, which is the Maori name for this building (meaning Hinemihi of the Old World), is referred to here in the third person as female because the Maori people believe she has living qualities based on their ancestral origins, and today the building retains both immense cultural significance and historic importance owing to her rarity.

Although Hinemihi has received conservation/restoration work in the past, the Trust is again starting to plan for a programme of conservation repairs to address mistakes made in earlier restorations and to ensure her long term future. Again, the importance of the cross-disciplinary approach will be key to the success of this future project, which will involve input from the Property Manager, the Building Team, and the Curatorial, Conservator and Archaeology Sections. Consultation with the Maori community is crucial to ensure the cultural significance of any work is fully appreciated, and involvement by Maori artists and craftspeople will also be essential.

|

|

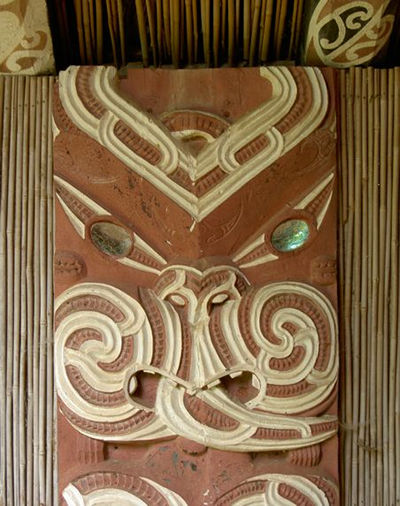

| The Maori Meeting House, Hinemihi o te Ao Tawhito and, below, a detail of the gable decoration.The building originally had a roof of wood shingles, not thatch. | |

|

HISTORY

Hinemihi was built in 1881 and stood in the village of Te Wairoa in New Zealand’s central North Island, in a district of hot volcanic lakes. On 10th June 1886 Mount Tarawera erupted, destroying the village and killing 153 of its inhabitants. Hinemihi was one of the few surviving buildings, and had provided shelter to numerous people during the eruption. Te Wairoa was abandoned and Hinemihi stood empty for six years. She was purchased by the 4th Earl of Onslow, who was Governor of New Zealand from 1889 to 1892. Hinemihi was dismantled and shipped with instructions for reassembly to England in 1892. Since that date she has stood within the grounds of the Onslow’s seat, Clandon Park in Surrey, which became a National Trust property in 1956. Hinemihi was presumably reassembled by Lord Onslow’s estate labourers. At some point during dismantling and reassembling (Hinemihi has stood at two sites at Clandon) the building was shortened and some of the carved elements were reaffixed incorrectly.

In 1978 Hinemihi was repaired by English craftsmen/builders and re-roofed with thatch which turned out to be a misinterpretation of a contemporary photograph showing her after the eruption covered with thick ash. Until then, whilst at Clandon Park, Hinemihi always had a traditional reed roof, whereas in her original position at Te Wairoa she had a wooden shingle roof, which Maori were using at that period in imitation of new European style buildings

Whilst Clandon Park remained in the ownership of the Onslow family, Hinemihi was an important reminder of the 4th Earl and his family’s links with New Zealand. Clearly, in being removed from Te Wairoa, Hinemihi has lost her original cultural purpose. However, during World War One she was cared for by recuperating Maori New Zealand soldiers and over the past 15 years or so Hinemihi has increasingly become a focus of Maori culture in the UK.

CONSERVATION

Hinemihi’s roof is failing and there will be a discussion as to which material will be most appropriate: traditional reed or totara wood shingles. The excellent photographic and documentary records of Hinemihi means that the original form of the roof can be accurately reconstructed.

Twenty-five years have passed since the last major repair work on Hinemihi, and the English climate has taken its toll. The insect-infested birch bark saplings that form Hinemihi’s internal roof covering may need to be replaced or repaired. The front of the building, which is the most decorative elevation, has twin carved pilasters or ‘Amo’. These have been raised on concrete bases to protect them from damp ground conditions. However, these plinths retain their original grey colour, impacting on the visual amenity of the building, especially in contrast to the painted red ochre of the pilasters. A proposal to paint these in an appropriate colour so that they are visually toned down may be put forward following further research and consultation.

|

|

| A side wall of the porch and (below) a detail of one of the carved posts | |

|

There is a need to protect the building from water ingress, insect, plant and animal damage. One of the most notable defects, especially to the rear of Hinemihi, is the decaying elm planking which is rotting from the ground up, some of which is holed. The appearance of salts on the interior would suggest that this is due to ground moisture. This has in turn caused the traditional matting hung on the interior walls to discolour and deteriorate. In many places this planking may need to be replaced with appropriate timbers. A damp course was inserted in the 1970s but this no longer seems to be wholly effective and the ground levels will need to be investigated. Boards are also being affected by rusting nails, which are failing and causing staining. Appropriate alternatives will also need to be investigated.

THE FUTURE

Hinemihi is unique not only to the National Trust, but also as the only Maori meeting house in the United Kingdom, and one of the few to be found outside New Zealand. Her huge significance makes it important that she is conserved and restored to the highest possible standard, so that she may continue to be enjoyed by visitors, and to fulfil her role in the ancestral traditions of the Maori people.

Recommended Reading

- Alan Gallop, The House With the Golden Eyes – Unlocking the Secrets of Hinemihi, the Maori Meeting House from Te Wairoa (New Zealand) and Clandon Park (Surrey, England), Running Horse Books, Sunbury-on-Thames, Middlesex, 1998

Useful Addresses

- The National Trust, Clandon Park, West Clandon, Guildford, Surrey GU4 7RQ

- The National Trust, Stowe Landscape Gardens, Buckingham, Buckinghamshire MK18 5EH

Notes

(1) G Jackson-Stops, 'Forgotten but not Lost', Country Life, 13th August 1992

(2) Information from Stowe: The Chinese House, Woodwork, Structural Condition Report and Conservation Recommendations, January 1997, Tankerdale Limited (by kind permission)