Church Buildings and the Community

Richard Chartres

|

|

| Richard Chartres Bishop of London and Simon Thurley Chief Executive of English Heritage at the Church of St Mary Magdalene, Paddington (Photo: Michael Walter, Troika) |

The Church of England has responsibility for 16,200 churches of which over 12,000 are listed. In all, there are 14,500 listed places of worship in England, and 45 per cent of all Grade I buildings are places of worship. As Dr Simon Thurley, Chief Executive of English Heritage has said, ‘The parish churches of England are some of the most sparkling jewels in the precious crown that is our historic environment’.

However, the cost of maintaining and repairing these buildings can be overwhelming. Research undertaken by English Heritage in collaboration with the Church of England estimated that necessary repairs to all listed places of worship are valued at £925 million over the next five years, or £185 million a year.(1)

WHAT IS ACTUALLY BEING SPENT?

Annual figures collected by the Church of England reveal that £112 million is currently being spent on repairs to parish churches. Public grants together with some independent trusts provide less than £40 million per year for repairs, which leaves a current annual shortfall of £72 million per year, or nearly 65 per cent, which is raised by the congregations.

Contrary to what many people still believe, the responsibility for maintaining church buildings and keeping them in repair lies with each individual church: the incumbent and the parochial church council. There is no guaranteed state funding for churches’ care or maintenance nor does the Church itself have central funds to put towards these buildings. As I have said before, the Church of England is, in financial terms, the most disestablished church in Western Europe. Across the continent churches are facing huge repair bills, and many other European countries support church organisations through public funds in various ways. Some countries take on financial responsibility for repairs, some grant compensation for ‘heritage costs’, others continue to levy a church tax on the population. There is, in this country, an asymmetrical funding relationship between Church and State.

SO WHAT IS THE ANSWER?

Because the emphasis has often been on ‘heritage’, as if church buildings belonged to the past, the assumption has been that any money, public or otherwise, spent on them is simply to preserve their antiquarian value. But these buildings are much more than a collection of grand historical set pieces, with no relevance to the lives of ordinary people.

The Church accepts that it has a duty to care for what we have inherited but also to develop the potential of these buildings to do what they were intended to do as servants of the whole community as well as places for the worship of God.

The idea of a church being a vital resource for the whole community is not a new one. Until the building of community and village halls, churches were the only buildings large enough to host community events. Records show that the parish church hosted meetings, debates, elections and legal proceedings, as well as festivities. It could also house the library and the local school, store any firefighting equipment, act as the local armoury, afford space for the stocks as well as at times being used as the jail and as a night shelter. In some cases, it even provided space for a gaming room, and records show that in some cockfighting took place until 1849.

Many today are continuing to play a significant role as venues for a range of social and community activities and as centres of education and tourism. National surveys in 2003 and 2005 found that 86 per cent of individuals surveyed had been inside a church building within the previous 12 months for a range of different reasons including funerals and weddings, but also for cultural and community events.(2) In 2005, 38 per cent said they had visited due to a social and community event and 23 per cent had gone in to find a quiet space. The same survey found that 72 per cent agreed with the statement, ‘places of worship provide valuable social and community facilities’. Among respondents who claimed no religious allegiance, 46 per cent agreed with this statement.

Churches can be part of the solution to a range of problems from providing a safe space for people to gather after a disaster – the flooding in the summer of 2007 being the most recent example – to longer term problems like addressing loneliness and deprivation in an ageing population, and the need for the provision of community support and services in deprived urban areas and scattered rural areas where most other institutions such as schools, shop, pubs and post offices have already left. Alongside the Methodist Church and the United Reformed Church, we have been developing national guidelines with Post Office Ltd that will help where a church is considering hosting an outreach post office. These guidelines cover requirements, procedures and good working practice for both the church and the post office on what is involved. We hope that this partnership will pave the way for other similar national initiatives.

In the last few years, surveys mapping the size and range of this contribution have been undertaken in all nine English regions. Most of these surveys have been undertaken by the regional faith network supported by their regional development agency or government office, or in some cases their local authority.

A 2005 study of the economic impact of faith communities in the North West estimated that they contributed over £90 million a year. This includes: the estimated economic value of 45,667 faith volunteers contributing over eight million hours of social and health care, and working in regeneration initiatives (equivalent to 4,815 full time jobs at a wage rate of £7.50 per hour); premises made available by faith groups for use of local community groups; and day visitor expenditure generated by faith tourism which also supported the equivalent of 215 full time jobs.(3)

In 2006, across the four local authority areas of Dudley, Sandwell, Walsall, and Wolverhampton, over 21,000 people from faith communities were actively working in their community as paid staff or volunteers, the latter contributing a total of 1.3m volunteers’ hours per year. As a result of their work, 57,000 young people were attending more than 2,000 youth activities. This contribution is estimated to be an investment of over £32 million a year in people resources.(4)

|

|

| St Leonard's, Bilston is at the heart of an urban community, not only as a place of worship and an architectural landmark but also through providing office accommodation for the Senior Citizen's Link line (above left) and as a quiet meeting place for coffee. |

In all of this, buildings make a significant contribution: a 2004 survey in the South East found that on average at least two projects of social action were carried out from the premises of each faith building in the region.(5) A 2006 survey across the West Midlands found that over 80 per cent of faith groups own buildings. Almost 90 per cent of respondents allow the wider community to use their buildings.(6)

Community use of churches ranges from provision of support services for various groups such as the elderly, and the homeless through to setting up community cafés, hosting concerts and exhibitions, providing venues for civic events, adult education, IT training, after-schools clubs and increasingly to help deliver essential services such as post offices, community shops and doctors’ surgeries, and police stations.

St Leonard’s Church, Bilston, is a Grade II church in a town hit badly by the closure of nearby heavy industry. In 1995 the congregation researched the needs of the local community and found that the needs of vulnerable local older people were not being met. Senior Citizens Link Line, which the church now hosts, is a support service that phones 1,500 elderly people every week. It employs seven staff and more than 40 volunteers supported by National Lottery funding. It is now extending its service to the Wolverhampton and Bradford areas and the Primary Care Trust now wishes to make use of it.

And yet, in so many ways, the potential of churches as a community resource and as part of schemes for social regeneration is underdeveloped.

In October 2004, the Church of England published Building Faith in our Future in order to awaken greater understanding of the contribution of church buildings.(7) The sustainability of this activity and of the buildings which enable it to take place, depends on the effort and commitment of the local volunteers who maintain them. All this activity is vulnerable without further help. The Building Faith Campaign is seeking a more realistic direct partnership between the Church and both central and local government and the public sector for the care and maintenance of church buildings in the interests of the nation as a whole. We would like to agree a new financial settlement which reflects the value and potential of these community assets.

|

|

| A playgroup in the nave of St Faith’s, Hexton: services are now held in the chancel. |

WHAT WE HAVE TO OFFER

The Church of England by its presence everywhere is uniquely placed to contribute. Of the 16,200 parish churches, over 9,600 (60%) are in rural areas.(8) This is more than the number of post office branches, which currently stands at around 14,600 in the UK, 55 per cent of which are rural.(9) Furthermore, the incumbent, the congregation and the church volunteers actually live in their communities. Churches are used to working with volunteers and have large buildings to offer. We are not simply asking for money for buildings, but saying that greater support will help keep these buildings in good repair, improve what they can offer to their local communities and thus would unlock a major resource for the nation as a whole.

WHAT ARE WE ASKING FOR?

Recognition that maintaining these buildings is expensive because of their (rightful) heritage importance. We are currently suggesting 50 per cent of the cost of repairs should be provided by the State.

Recognition that maintenance, if routinely carried out, can avoid huge repair bills in the future. Several dioceses including London Diocese are exploring providing centralised maintenance schemes for their churches. Supported by Heritage Lottery Fund, English Heritage and the Council for the Care of Churches, SPAB’s Faith in Maintenance project, which started this year, aims to provide 30 free training courses for over 6,000 volunteers in England and Wales who help to maintain our historic places of worship. This needs to continue beyond the three years set for the project and we need a long term funding scheme to help churches pay for the actual work.

Recognition that many of these buildings cannot become full community assets without expensive alterations. Places of worship usually lack essential facilities such as lavatories and kitchens. Because they are historic buildings, adapting them requires careful design and implementation and the work is often expensive. A 2005 survey of Church of England churches has revealed that some 44 per cent of churches now have toilets and some 37 per cent have kitchen facilities.(10) This is good news – a church with such facilities immediately has so much more to offer as a resource – but there is still a long way to go.

The inclusion of churches in all national, regional and local strategic policies. Whether it’s about regeneration of urban areas or how best to deliver vital services to rural areas, the role of churches must be considered strategically.

A level-playing field in relation to other funding. Most faith groups are very clear about the difference between funding their own faith activities and funding activities which support the wider community. It’s a shame that some funding bodies are not so clear.

WHAT WE ARE DOING

We believe that the Church’s contribution to the community in so many ways justifies greater government funding and we are taking this forward with them in discussion.

But we recognise that the churches themselves must do more to become more professional in their requests for funding. Congregations are sometimes unfamiliar with the jargon and also lack the skills to be able to capture and articulate all the benefits arising out of their projects. Faith groups are more likely to talk of ‘well-being’ rather than economic benefits. Within dioceses and at the centre we are already working with a range of existing organisations, both private and charitable, to address this issue of capacity and to put in place training to help churches make more professional grant applications.

The ChurchCare website (www.churchcare.co.uk), which was developed by the Church of England in 2001 in partnership with the Ecclesiastical Insurance Group, is a ‘one-stop shop’ resource for anyone involved in the running of a church building. The site covers a range of topics related to maintenance, fundraising and finance, legal matters, security and insurance. Currently being updated for a relaunch in the autumn, new sections are being added on the repair, extension and alteration of church buildings, and the development of the building as a community resource. All of these will take the user through the stages involved, such as for undertaking major repair projects, and for developing and managing community projects, signposting at each stage useful links to sources of expertise and advice.

By using these buildings to their full potential as a real resource for their local communities, this will in turn help sustain them. While as we know not all these activities will produce funds, and indeed this is not their first objective, every time someone from the wider community enters a church building and they gain something worthwhile, it will encourage them to value it and to want to take a share of the responsibility for it. If nothing else it can mean that they get used to being in ‘a church’ comfortably.

At the very least, the church building itself benefits from more frequent use, regular heating and additional funds and volunteers and being valued more by its community.

We are continuing to encourage churches to open. Statistics show that open churches are safer from thieves and vandals than locked ones. The results of a 2005 survey indicate that half the Church of England’s churches are now open for more than ten hours a week and many for longer, while only 20 per cent are always closed to casual visitors outside service times.(11) The number of visitors to parish churches each year, while more difficult to quantify, has been estimated to be at least 10m visits, and may be as many as 50m.(12)

St Thomas’s, Stanley Crook, Durham, is a Grade II church where the closure of the mine has left a small community of high unemployment. Regularly considered for closure, the church survived due largely to the will of the community. A millennium project converted the west end of the nave to provide two-storey accommodation with a gallery at first floor level, a meeting area on ground floor with adjacent kitchen and toilet facilities. There is now a coffee drop-in, a charity shop and a library for mums and toddlers. Links have been made with the arts department of Sunderland University to encourage young artists to use the gallery as an exhibition space. Exhibitors are now also being attracted from across Europe. It has helped to rebuild a community; leaders have emerged from a community that has suffered greatly from unemployment.

St Faith’s, Hexton, Diocese of St Albans, is a Grade II* church which was facing the possibility of redundancy. By using the chancel for worship and opening up the nave to the community, it has turned itself around. The pews have been taken out, a wooden floor put in and a kitchen and toilet installed at the base of the tower. The local primary school uses it as their hall. It also provides a venue for a playgroup, youth group, other community groups, IT learning, festivals and other events. It was a finalist in the 2005 Ecclesiastical Insurance Group competition, and was commended by the organisers: ‘The changes and improvements St Faith’s has made make it not only the physical centre of the village but also the spiritual and social centre of the community too'.

|

|

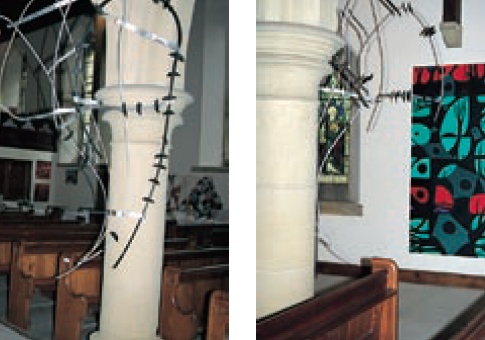

| St Thomas's, Stanley Crook: (left) sculpture by Kim Neashan, (right) painting by Katherine Henery (Photos: Virginia Bodmain, University of Sunderland) |

WHAT ARE THE ALTERNATIVES?

Sir Roy Strong, in A Little History of the English Country Church (Jonathan Cape 2007) advocates giving the 'church building back to the local community, albeit with safeguards for worship…. Change has been the life-blood of the country church through the ages. Adaptation will be more important than preservation'. We welcome this. One of the great steps forward in the last few years is the stronger recognition throughout the conservation world that over insistence on ‘preservation’ may fossilise the very thing they wish to retain. Sensitive adaptation, underpinned by understanding of the building, must be the way forward.

We are aware that there is a problem in that most churches are in less populated areas. The distribution of listed parish churches is heavily biased towards sparsely populated parts of the country. 49 per cent of all listed parish churches, and 61 per cent of Grade I parish churches are located in the East Midlands, the East of England and the West Country, which contain only 26 per cent of the population.(13) Obviously parishes and dioceses need to think strategically about their own mission and future. Advice on this has been produced and many churches and dioceses are taking this very seriously.

We have also seen a much richer co-operation between the many bodies, organisations and people who appreciate and love church buildings – for their sense of the presence of God, for their beauty, and because of what they enable the community to do. We need those supporters to rally to support this campaign.

~~~

Notes

(1) Section 5.6, Places of Worship Fabric Needs

Survey 2005, a report for English Heritage

and the Council for the Care of Churches by Michael Wingate, published May 2006; available from the English Heritage website:

www.english-heritage.org.uk/inspired

(2) Opinion Research Business (ORB), Annual

Religious Survey of Affiliation and Practice

including Perceptions of the Role of Local

Churches/Chapels, on behalf of the Church

of England and English Heritage, Oct 2003

and Nov 2005

(3) DTZ Pieda Consulting, Faith in England’s

Northwest: Economic Impact Assessment,

produced on behalf of the Northwest

Regional Development Agency and the

Churches’ Officer for the Northwest,

Feb 2005

(4) Faith in the Black Country: the role of faith

groups in community transformation,

commissioned by the Black Country Net,

with funding from the Home Office’s Faith

Communities Capacity Building fund and

Equal (Black Country in the Lead): study

conducted by Transformations Community

Projects Partnership, 2007

(5) Beyond Belief?: a research report from

the South East England Faith Forum,

March 2004, jointly funded by SEEDA and

churches in the South East with support

from RAISE and SEERA

(6) Believing in the Region: a baseline study

of faith bodies across the West Midlands,

May 2006. West Midlands Faith Forum

mapping study on contribution of Faith

Groups in the West Midlands undertaken

by Regional Action West Midlands (RAWN)

with funding from the Government Office

West Midlands

(7) Church Heritage Forum, Building Faith in

our Future, Church House Publishing, 2004

(8) Government Rural and Urban Area

Classifications 2004

(9) Postcomm 5th Annual Report 2004-5

(10) Church Statistics collected by the Research

and Statistics Department, Church of

England, 2005

(11) Church Statistics collected by the Research

and Statistics Department, Church of

England, 2005

(12) Trevor Cooper, How do we keep our Parish

Churches? Ecclesiological Society 2004

(13) 'Insights’ Tourism Intelligence Papers,

Volume 12(A13) (English Tourism

St Thomas's, Stanley Crook: (left) sculpture by Kim Neashan, (right) painting by Katherine Henery Council 2000), pp43-52