Energy and Heritage

The challenges faced by traditional buildings in a carbon neutral world

Tim Yates

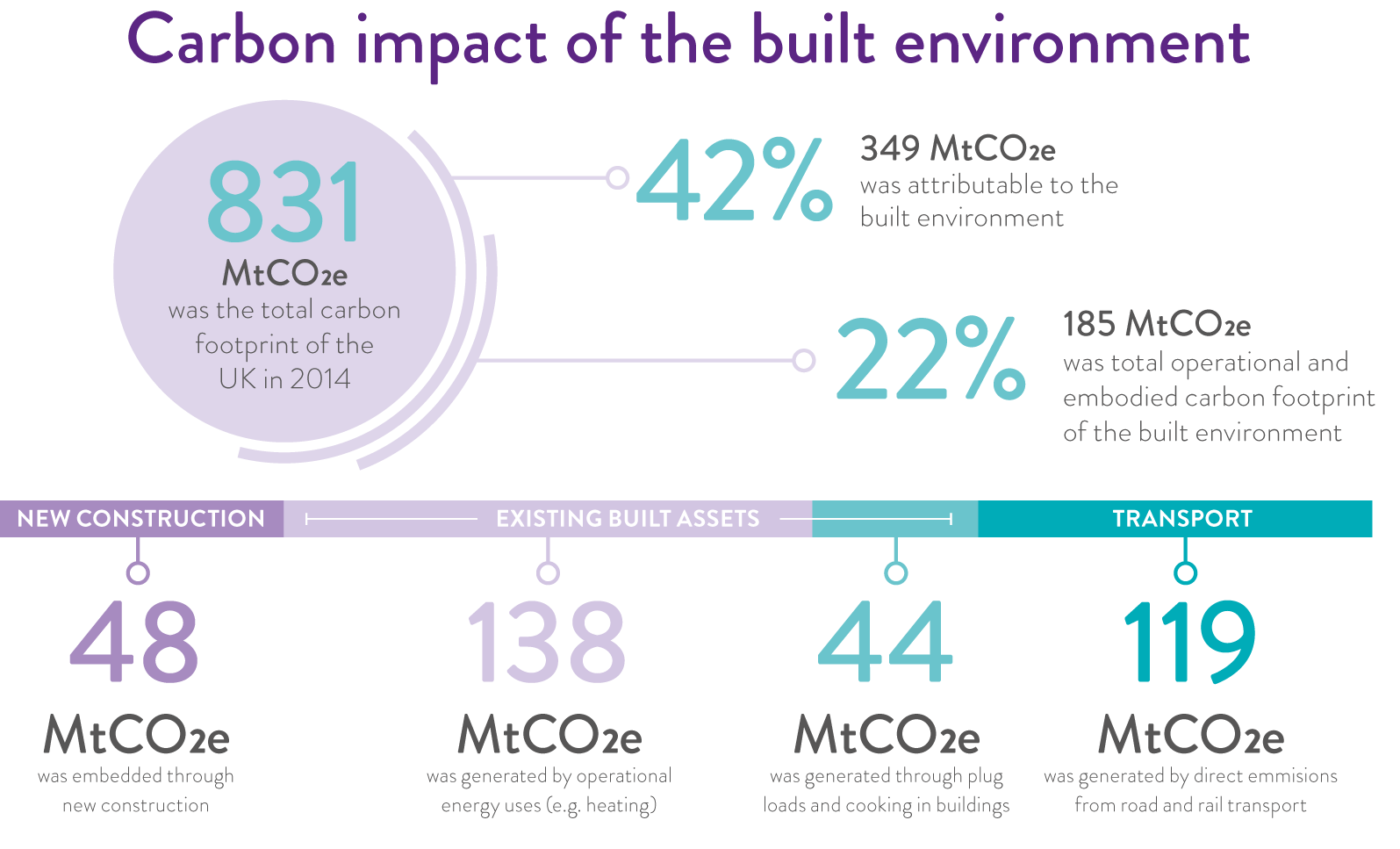

Infographic courtesy of the UK Green Buildings Council

The need to respond to climate change and the challenge to become carbon neutral are very much part of our world in the 21st century, but it has taken many years to reach this point. It is now more than 35 years since the first International Conference of the Assessment of the Role of Carbon Dioxide and of other Greenhouse Gases in Climate Variations and Associated Impacts was held in October 1985 in Villach, Austria and it is even further back to the first warning of the potential impact of burning of fossil fuels on our climate raised by Svante Arrhenius in 1896.

It is also a long time since the need to refurbish and renew our housing stock was first raised by politicians. Of course, we have always renewed homes, as new designs, materials and ways of living became popular, but in the years following the end of the Great War it became a more pressing issue. The Tudor Walters Committee, set up in 1917, is seen as the most important of the various government committees tasked to advise on housing problems. The report of this committee was in effect a housing manual covering all aspects of the design and construction of dwellings for the working classes. In November 1918, Prime Minister David Lloyd George said there would be ‘habitations fit for the heroes who have won the war’. The press picked up on this and changed the wording to the snappy and now familiar phrase Homes Fit for Heroes.

In 1919 the newly formed Ministry of Health asked the Department for Scientific Research to undertake research into the scarcity of materials required for building and the shortage of skills to construct suitable houses. This led to the establishment of the Building Research Station, now known as the Building Research Establishment (BRE), in 1921 and a renewed interest in the provision of affordable housing through local council initiatives. This was a phase of housing renewal driven by health and the needs of society. Some older housing, often in poor condition and in some cases poorly constructed, was cleared but many houses remained. It is these buildings that are now the stock of traditional housing that provide homes for many in both our towns and cities and villages, and which are once again the focus of government initiatives.

The years after the Second World War saw the demolition of further large areas of housing, including both properties damaged by bombing and clearances to make way for new developments in response to the demand for housing in the baby boomer era. By 2000 attitudes to existing housing were starting to change but there were still large numbers of houses which lay empty and which were becoming increasingly neglected. Part of the response to this situation was the UK Government's Sustainable Communities Plan set up in 2003. It established nine housing market renewal (HMR) Pathfinder areas, designed primarily to tackle the problems associated with low demand housing and to improve market conditions in the north of England. These areas covered some 700,000 dwellings, including about half of the one million homes affected by low demand and abandonment. The Pathfinder areas were supported by £1.2 billion of government funding which was earmarked to deal with the most acute problems, to provide models for successful renewal elsewhere and to stimulate wider regeneration.

It was against this background that the BRE Trust commissioned two reports entitled Sustainable refurbishment of Victorian housing: Guidance, assessment method and case studies in 2006 and Knock it down or do it up? Sustainable housebuilding: New build and refurbishment in the Sustainable Communities Plan in 2008. Both reports looked at the tension which had developed between the need to improve and sell properties within the limits of market values and the requirement to create safe, warm and secure homes while retaining our built heritage. This time the driver for housing renewal was economic, but once again it was the built heritage and the people who lived in this housing which were most greatly impacted.

In 2012 the Green Deal initiative was established to improve the energy efficiency of the existing housing stock. However, its success was limited and by the time it ended only 15,000 grants had been distributed. Then in 2016 the Each Home Counts report identified a series of actions which were intended to tackle energy efficiency in existing dwellings and the fuel poverty which is so often linked to thermally inefficient housing. The focus was on energy and the need to improve our existing housing stock as we moved towards the UK target to bring all greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050. Given that around 40 per cent of emissions are associated with the built environment and half of these with the functional operation of buildings such as heating and lighting, then improving energy efficiency is essential.

Of course, this goal brings with it challenges and tensions. Between 65-80 per cent of the buildings which will exist in 2050 have already been built and as a result focus needs to be placed on existing housing stock, 25 per cent of which is traditionally constructed and forms a central part of our built heritage. In England, Building Regulations Approved Document Part L 1B Sections 3.7 and 3.8 gives guidance on historic and traditional buildings where exemptions or special considerations apply. Similar regulations are applicable in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The special considerations are described in Section 3.9:

When undertaking work on or in connection with a building that falls in one of the classes listed above [3.7 and 3.8], the aim should be to improve the energy efficiency as far as reasonably practical. The work should not prejudice the character of the host building or increase the risk of long-term deterioration of the building fabric or fitting.

The Approved Document recognises that any work on buildings which alters their fabric requires care and attention to detail. Consequently, it is important that guidance is provided and that those involved both in specifying and undertaking the work are appropriately trained and qualified. These needs were emphasised in the Each Home Counts report and from these recommendations the UK Government has supported the development of a series of Publicly Available Specifications (PAS). These are documents produced in consultation with the British Standards Institution (BSI) which define standards for good practice, products, services or processes. They include Retrofitting dwellings for improved energy efficiency. Specification and guidance (PAS 2035/2030), Certification of energy efficiency measure installation in existing buildings and insulation in residential park homes (PAS 2031) and, still in preparation, Retrofit of Commercial Buildings (PAS 2038).

Currently retrofitting energy efficiency measures focus on improving the insulation of the roof and walls, restricting moisture and reducing draughts from windows and fireplaces. While these actions may be appropriate for some buildings, they do not necessarily consider the specific needs of traditionally built properties. The fear is that those involved in the specification and installation of energy efficiency measures will not understand traditional buildings which will result in unintended consequences for the building fabric and the occupants. What is required is a good awareness of what can and cannot be done when juggling the competing demands of energy efficiency improvement with the need to maintain the character of these buildings or increasing the chance of damaging their fabric or fittings.

Traditional buildings need procedures in place which ensures that those involved in their energy efficiency improvement have a good understanding of the significance of the building and of the technical issues and challenges involved. Fortunately, this is covered in BSI standard BS 7913: 2013 Guide to the conservation of historic buildings drafted by BSI Committee B/560 who also monitor the development of the PAS 2030 series. BS 7913 describes best practice in the management and treatment of historic buildings and is applicable to historic buildings and traditional buildings with and without statutory protection. It provides little detail on energy efficiency measures, but it does outline essential guidance on assessing the significance of a building and on decision making in relation to the technical issues encountered in traditional buildings.

Overall traditional buildings need a holistic approach which looks to improve the energy efficiency of the existing fabric of the building rather than retrofitting something new. For example, dealing with a moisture problem by allowing the fabric to breath rather than by trying to stop moisture entering with a barrier, which can trap moisture inside. The challenge for BSI Committee B/560 is to embed the processes found in BS 7913 within the PAS 2030 series and in the training of those required to assess and improve the energy efficiency of traditional buildings.

It is now firmly acknowledged that climate change is a real threat and that urgent and immediate action is required. It is the task of those involved in the provision of guidance to steer a course which addresses the emission of greenhouse gases while conserving the buildings which form such a key part of our built environment and heritage. In the future our descendants may well look back and wonder why we were so slow to reduce greenhouse gas emissions but let us hope that they do not also wonder why so few traditional buildings remain in good condition!

Recommended Reading

Svante Arrhenius, ‘On the Influence of Carbonic Acid in the Air upon the Temperature of the Ground’, Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, Series 5, Volume 41, pages 237-276, April 1896Bonfield, Peter, Each Home Counts, DCLG, December 2016, http://bc-url.com/bonfield

HMSO, Report of the Committee appointed by the President of the local Government Board and the Secretary for Scotland to consider questions of building construction in connection with the provision of dwellings for the working classes in England, Wales and Scotland and report upon the methods of securing economy and dispatch in the provision of such dwellings, London: Cd. 9191, 1918

PAS 2030/2035, Retrofitting dwellings for improved energy efficiency. Specification and guidance., BSI, 2019

PAS 2031, Certification of energy efficiency measure installation in existing buildings and insulation in residential park homes., BSI, 2019

PAS 2038 (in draft): Retrofit of Commercial Buildings., BSI

Knock it down or do it up? Plimmer, F et all, - www.brebookshop.com/details.jsp?id=321561, 2008

Sustainable refurbishment of Victorian housing, Yates, TJS, www.brebookshop.com/details.jsp?id=286929, 2006

Approved Document L1B: conservation of fuel and power in existing dwellings, 2010 edition

www.eci.ox.ac.uk/research/energy/downloads/40house/40house.pdf www.ukgbc.org/climate-change/