Cobble Repairs

Robin Russell

|

|

| Tightly packed flat-topped cobbles bound by small kerb stones provide a relatively even surface at St Peter's, Tiverton, Devon |

A wide variety paving using locally-available small stones can be found in churchyards across the UK. Lying forgotten within their hallowed grounds, they are often the last surviving examples of the traditional surfaces used on neighbouring streets and paths, so give a valuable insight into the appearance of the local townscape before it became covered in tarmac. Generally, these ‘small-unit’ materials fall into two categories; cobbles or setts.

Small stones which are cut and shaped, often quite roughly, are now known as setts, although many people still refer to them as cobbles, In areas of the country where the local stone was easily split, thin setts are sometimes end-bedded or ‘pitched’ into the ground. (The term pitched has nothing to do with the use of bituminous pitch.) Granite setts are the most hard-wearing and can be found furthest from their source as they often replaced softer local stones following the development of canals and then the railways to transport them.

The term ‘cobbles’ describes the smoother, more rounded stones that were fashioned by natural erosion or running water, and were used uncut, as found. Cobbles were used extensively to create paths, roads and hardstanding areas, such as courtyards. Cobble-laying is a simple but very useful technique, but unfortunately, as with other trades, the knowledge of how to do it well has largely been lost as cheaper and often less effective methods have been adopted.

Where cobbled paths have survived, it is important to carry out repairs using appropriate materials for both cobbles and bedding, and to preserve as much of the original scheme as possible. At the outset of a project it is therefore important to identify which areas of the cobble are to be repaired. Photographs and sketches should be used to clearly communicate the nature and scope of the work to any contractors and controlling authorities. The key principles are:

Documentation – record the cobble before intervention and document the intervention itself so that future conservation work is well informed

Minimal intervention – retain the maximum amount of historic cobble and repair rather than replace wherever possible

Reversibility – ensure that alterations and additions to cobbled areas can be undone without harm

Like-for-like – wherever possible, match materials and techniques to the existing work

Appearance – make the solution honest but aesthetically neat or invisible: there is no justifiable reason why modern repairs, once aged, should not add character and appeal in the same way as historic ones.

Traditionally, cobbles were laid in non-porous subsoil, especially clays, and it is generally best to copy what went before. Often some coarser binder was added, such as a local sand or grit. More recently lime (or sometimes cement) mortars have been used but they are not recommended unless vehicles will be using the area. The original materials were probably sourced locally so it is best to try to find matching cobbles and subsoil locally too if possible.

Patterns or even lettering were often formed in cobbles by laying stones of the same or similar types in different directions, or by using different colours or types of stone. These may not be immediately obvious, so when relaying cobbles it is important that each one is placed back in the ground in the same orientation as before.

|

|

|

|

| Above left: St Swithuns, Sandford, Devon – some areas have sunk and collect water, but otherwise this section is in good repair. Centre: ugly concrete infill and cement repairs. Right: another inappropriate repair using mismatched stones | |||

Sourcing appropriate cobbles is the most difficult and time-consuming aspect of cobble repairs, and is best done before any work commences. Many traditional cobbled areas are made from flat-topped cobbles, which were usually found in local streams and river beds. The stones were flattened and smoothed uniquely over the centuries by the passing of water, silt and other material. They were placed with the flattened side on show.

Rounded cobbles, which are commonly found on beaches where they are shaped by being washed up and down and tumbled by the waves, should not be used as a substitute. Bear in mind that those dug from the ground may also have been formed on beaches, many millennia ago. They are not the same as river-worn cobbles. Consequently it is important to try to source the cobbles from a similar place to the originals.

River cobbles can no longer be extracted in this country, and the cobbles which are available from quarries are usually rounded beach-type cobbles. The best solution is to find cobbles salvaged from earlier schemes. Local authorities used to store the cobbles which were extracted from culverts or when relaying roads, but few still do so, and specifiers may find themselves passed from pillar to post in the hope of finding mythological depots. Private estates are more likely to retain cobbles from similar sources, although finding the shapes and sizes required may involve a great deal of sorting.

|

|

|

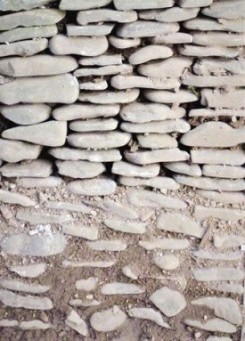

| Plants removed from cobble revealing a worn original earth mortar infill | Cobbles partially backfilled with sub-soil, showing the flat-topped form of reclaimed river-worn cobbles |

Cobbles were traditionally set into rammed subsoil which was laid for the purpose in the area to be cobbled. The stones were set into the subsoil by hammering them home so that they were touching adjacent stones.

Additional bedding material was packed between the touching stones to help to stabilise them, and longer stones were hammered deeper to further improve the key and prevent movement. Usually, these ‘peg-stones’ are distributed fairly evenly across the scheme, but in some places all the stones are found to be peg-shaped and hammered in deeply.

The process is rather like building a stone wall on its side and the bedding material is like the mortar. The tools are simple and include hammers of various sizes, shapes and materials to knock the stones into place evenly. A large mallet and a timber board are particularly useful. Spades and a crow-bar also come in handy, initially to prise stones from position and later, to back-fill the substrate between the stones.

A string-line is used to help position the top edge to present an even surface, which is then stabilised by infilling between the stones with a loose subsoil, brushed and packed in place using a stiff hand-brush similar to a churn-brush. It is usually best to water the repair area, for example with a watering-can, then infill again if any of the material washes in too deeply.

Where the cobbled area is not bordered by walls or heavy stone kerbs, the edge must be particularly well constructed if rapid deterioration is to be avoided. In this case, the edging stones can be fixed with a mass of lime mortar sloping into the ground (‘haunching’), which can be covered over, for example with grass, to disguise it.

|

|

| Calcite lettering on a path at St Peter’s, Tiverton |

Most importantly, the cobbled area must shed water. It should always have a camber to the edges and should generally be made of a non-porous material so that rainwater is shed to the outer edges. It is important that the rainwater is then carried away or drains quickly.

Areas which have sunken and so collect water are defective and should be repaired by bringing them up to the level of surrounding cobbles. Often sunken areas result from vehicles such as cherry-pickers or vans passing over cobbles which were not designed to carry such traffic.

Repairs in the past have often been carried out in unsuitable materials. It is vital to repair surrounding areas using similar methods to the original work.

Cobbles are easy to maintain and, as always, a stitch in time saves nine. Cobbled areas should be inspected regularly, taking particular care to identify areas where the cobbles are becoming loose. If appropriate action is taken quickly, cobbles can usually be repaired.

The most likely deterioration is where the infill between stones is lost, or the edging of the cobbled area is defective, causing individual stones to become loose. Also, areas of cobble sometimes sink, usually as a result of being driven over but occasionally because the substrate is subsiding. A sunken area of cobble will not shed water effectively.

Cobble repairs are more challenging when they form part of a much bigger project with a fixed timescale. In this context it is important to recognise the cobbling for what it is: a significant risk area which the project manager should prioritise as early as possible to ensure that the right materials are sourced and that a suitably skilled contractor is engaged.