The Use of Reinforced Concrete in Early 20th Century Churches

Elain Harwood

|

|

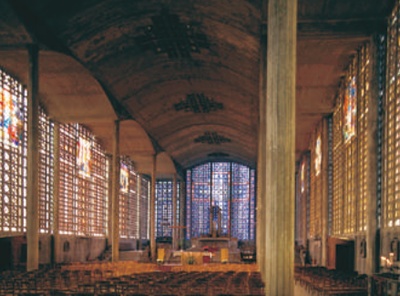

| Interior and exterior (below right) views of Auguste Perret’s Notre Dame du Raincy (1922-23), a seminal work which inspired British architects |

With the fusion of mass and tension found in the arch and arcade, it is perhaps not surprising that reinforced concrete rapidly became used for building churches. Although mass concrete was useful for foundations and mass walling from the early 19th century, it was with the introduction in France of iron beams within the mix from the 1850s that the potential of concrete began to be realised.

As early as 1864 concrete was used for the walling of a church at Le Vésinet, near St Germain-en-Laye, although the internal vault was entirely of iron. The incorporation of a mesh of iron rods and hoops to give added strength began to be recognised in Britain from the 1870s, but it was in France that concrete began to be systematically reinforced with first iron and then steel, and in 1892 François Hennebique patented his steel reinforcements.

The idea of reinforced concrete as a frame construction, capable of bridging great spans and window openings because it worked in tension as well as compression, was a boon for factory construction, but its decorative potential was also proven in church architecture. St Jean de Montmartre was built in 1897-1905 to the designs of Anatole de Baudot, a church specialist and Inspector of Ancient Monuments. Here reinforced concrete was applied to round-arched Gothic forms, both in the soaring main vault and in the side arcades.

In England, mass concrete was used for the vault at All Saints, Brockhampton, by WR Lethaby in 1901-2. More interestingly, ‘concrete reinforced with expanded steel’, as the plans state, was used by Charles Reilly for the barrel vaults and crossing dome at the mission church of St Barnabas, Hackney, in 1909-11. The walls were of brick. Mission churches such as this were technical as well as social experiments, and the first wholly reinforced concrete church seems to have been another, the Clare College Mission of 1911 in Dilston Grove, Southwark. The architects, Simpson and Ayrton, later used concrete extensively for the Wembley Exhibition and accompanying stadium of 1923-24.

|

Much larger in scale is the remarkable church of St John the Evangelist and St Mary Magdalene, Goldthorpe near Doncaster, which was built in 1914-16 at the behest of the Second Viscount Halifax to serve a growing colliery district. Quite why concrete was chosen is unknown. What is extraordinary is that reinforced concrete was used for such an ambitious, High Anglican church, complete with an Italianate campanile. The structure is entirely made of reinforced concrete, with concrete trusses and concrete walls 200mm thick. Even the internal sculptures and altar are of concrete. The church was restored in 2000-2 with a large grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund.

Internationally, the concrete church of the inter-war years is Auguste Perret’s Notre Dame du Raincy, a First World War memorial. It was built in 1922-24 on a limited budget as a ‘hall’ church in which nave and aisles are the same height and from which the sanctuary is undivided. Perret could have provided an undivided span, but chose to incorporate arcades of slender, unmoulded columns and a barrel vault just 50mm thick.

The external cladding was also of concrete pre-cast slabs that were a tessellation of geometric shapes filled with brilliantly-coloured glass by Maurice Denis. This reflects Raincy’s importance in the emergence of L’Art Sacré, a movement that united artists, architects and craftsmen to bring art that was aesthetically challenging as well as devotional into churches. After another war, Le Corbusier’s Notre Dame du Haut at Ronchamp was a product of the same movement.

Perret’s church had a huge influence across Europe, most notably at St Antony, Basle, a very grand church of 1927, and at Rudolf Schwarz’s tiny Corpus Christi, Aachen, a pristine rectangular box of white rendered concrete consecrated in 1930. The nearest British progeny was perhaps St Andrew, Felixstowe, a remarkable work of 1930-1 by Hilda Mason and Raymond Erith. However, in a letter to the Bishop of St Edmundsbury, Mason cites Perret’s church as ‘a type we wished to avoid’. Had the architects’ wish for coloured glass been fulfilled, the similarity would have been still greater. The church reflects East Anglian Perpendicular traditions, but it is entirely constructed of reinforced concrete save for the brick-lined clerestory windows.

|

|

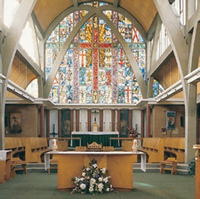

| St Barnabas, Hackney (1909-11), showing Charles Reilly’s use of reinforced concrete for the barrel vaults and dome |

In the 1930s reinforced concrete was regularly used within a brick cladding, its arched trusses providing a semblance of a Gothic vault just as Baudot had realised much earlier. Seely and Paget made a feature of catenary or parabolic arches, based on the natural form of a hanging chain, as an honest and economical expression of engineering forces.

Giant arches frame the nave and sanctuary of their first church, St Faith, Lee-on-the-Solent of 1933, with small arches for the side passages. The form was first used by Heinrich Kuster at Breslau Market Hall in 1906-7, but was not copied widely in Britain until after its striking adoption in 1927-8 by Easton and Robertson for the New Royal Horticultural Hall in Westminster.

Similar arches are found in many of Seely and Paget’s best churches into the 1950s, especially at St Andrew and St George, Stevenage, of 1957-60. There the arches are pre-cast, pre-stressed, and set in pairs, extending outwards to give the effect of flying buttresses and appearing internally as pointed arches at their intersection. As at St Faith’s, the construction permits large clerestories which fill the church with light.

NF Cachemaille-Day used the Diagrid system of reinforced concrete construction to span his churches, essentially a grid of squares placed diamond-wise and supported on columns. His star-shaped St Michael and All Angels, Wythenshawe, Manchester, from 1937, is the most powerful example, essentially a square within a square and originally planned with a forward altar. He used the system on a more modest scale within the brick rectangles of St Paul’s, Dollis Hill, in 1939 (now the Maharashta Mandal, London), St Barnabas, Tuffley, Gloucester in 1939-40, and at St James, Clapham Park, from 1957-8. There the geometrical pattern gives the optical effect of a true tierceron vault, that is to say a ribbed vault which has additional ribs (tiercerons, from tierce, third) similar to a fan vault. In this case the effect is heightened by having solid spandrels where they spring from the walls. An extra set of columns denotes the chancel.

|

|

|

| Interior and exterior views of St John the Evangelist and St Mary Magdalene, Goldthorpe, South Yorkshire (1916), by AY Nutt | ||

Cachemaille-Day’s mentor, HS Goodhart-Rendel, also used concrete imaginatively in his later churches, as at Holy Trinity, Dockhead, of 1958-60, where the vault is of thin concrete, reinforced with Delta bronze for longevity.

One of the most extraordinary uses of reinforced concrete for a religious building was that by E Owen Williams for the Dollis Hill Synagogue in 1935-6, for which he was commissioned following the success of his Pioneer Health Centre as a building that was cheap yet ‘dignified’.

Williams promised a building for £9,500 ‘all in’, and whose future maintenance costs would be ‘negligible’. In fact it cost twice as much. The zigzag side walls gave extra support to the cantilevered ladies’ galleries, while concrete made it easy to form windows in the shape of the Star of David and the menorah or seven-branched candelabra. Even some of the furniture was designed in concrete.

In the immediate post-war period, reinforced concrete was the natural material to use due to its cheapness and availability. Bricks and steel remained in short supply even after the end of building restrictions in November 1954, allowing church building to resume. It is possible to pick out only the most striking examples here. Sir Giles and Adrian Gilbert Scott turned to the parabolic arch as a basis of construction, Sir Giles initially with his rejected designs for the rebuilding of Coventry Cathedral in 1944, and Adrian at St Leonard’s, St Leonard’s on Sea, Hastings, of 1953-61 and at SS Mary and Joseph, Lansbury. The latter, was part of the Festival of Britain’s ‘Live Architecture’ show at Lansbury, belatedly built in 1951-4.

|

||

| St Peter’s, Gorleston-on-Sea (1938-39) by Eric Gill |

Younger architects were more inventive.

Basil Spence used concrete for the internal

structure of Coventry Cathedral, a design

won in competition in 1951 and consecrated

in 1962. He substituted concrete for stone

walling in the interior, and for the construction

Chapel of Unity and Guild Chapel, when the

design had to be cut back in 1955 to save

money. In the same year he designed three

churches for new housing estates in Coventry,

using money granted by the War Damage

Commission to replace one bombed city centre

church. Meetings with the builder Wimpey

led to the use of ‘no fines’ concrete - literally

concrete with only large aggregate. The lack of

sand made for a light, dry and

well-insulated

construction with the texture of a Swiss

cheese, but prevented large window openings

save at the east and west ends where pre-cast

reinforced members gave support. The three

churches have the same ingredients set out in

a different arrangement on each site. These

include a detached, open-framed bell tower

which was to become a common feature of

post-war churches, including Spence’s more

lavish St Paul’s, Sheffield (1958-9).

Concrete is to be found, with brick, in many of the most inventive post-war churches, notably in the work of Maguire and Murray, which re-evaluates the centrally-planned church of the Renaissance in modern forms. Their central cupolas, including the massive oast house form at West Malling Abbey, rest on huge reinforced concrete ring beams. More immediately spectacular is the use of shell concrete vaults. It was found in the 1920s that very thin structures of reinforced concrete could bridge great spans by a balance of tension and compression. A German development first used in the 1920s, the technique was only slowly adopted in Britain before the late 1940s.

|

|

| St James’, Clapham (1957) by NF Cachemaille-Day | |

|

|

| St Andrew and St George (1962-63), Stevenage by Seeley & Paget | |

|

|

| St John the Divine, Lincoln (1962-3), a fine example of an anticlastic shell structure by HS Scorer |

A lecture in 1957 by Felix Candela and increasing interest in the work of Oscar Niemeyer, including his wavy arch-roofed Church of St Francis, Pampulha, of 1940, encouraged a brief but exciting venture into two-way or anticlastic hyperbolic paraboloid roofs. An anticlastic shell may be made so that each line from edge to edge is actually a straight line or ‘ruled’ surface, making the often tricky formwork easier to develop from wooden planking and allowing the possibility of pre-stressing. The tensioning of the reinforcement rods, a development only just coming into British architecture in 1939, gave concrete roofs greater strength.

Reinforced concrete has an important role in the many Roman Catholic churches built in the post-war years. The programme of church building was strengthened in the 20th century by many architects from overseas. It realised one remarkable concrete church by an Italian immigrant, Giuseppe Rinvolucri, in the 1930s; Our Lady, Star of the Sea, at Amlwch, Anglesey, which was built of parabolic stressed concrete ribs in 1936.

In the post-war period the lead was taken by Polish refugees, for whom a School of Architecture was established in Liverpool in 1944. The most remarkable churches were by Jerzy Faczynski, including St Ambrose, Speke, a square church of 1960, and the circular St Mary, Leyland, consecrated in 1963 and another synthesis of architecture and art, with glass by Reyntiens, ceramics by Adam Kossowski and sculpture by Arthur Dooley.

But the most remarkable group of post-war churches is that designed by the firm of Gillespie, Kidd and Coia, mostly for the Diocese of Strathclyde in and around Glasgow. The designers were two young assistants, the Highland Presbyterian Andy MacMillan and the Jewish emigré Isi Metzstein. Their first church, St Paul’s, Glenrothes, Fife (1954-6), was not only liturgically advanced with a forward altar and a fan-shaped congregation, it was stylistically iconoclastic with its simple white harling and black glazing on a concrete frame, and powerfully directed but hidden sources of light.

Their later churches have had difficulties: the leaking St Benedict’s, Drumchapel, was demolished in 1991 while under consideration for listing, while their masterpiece, St Peter’s Seminary, Cardross, Dumbarton, lies derelict. The campanile of their largest parish church, St Bride’s, East Kilbride, was demolished in 1983. Le Corbusier was one influence, but MacMillan emphasised the importance of Scandinavian architects such as Peter Celsing. Enough of their work, notably St Bride’s (1963-4) and St Patrick’s, Kilsyth (1961-5), survives to show their mastery of sculptural form, usually in the form of concrete roofs set over brick and concrete walling.

Concrete has generally been most successful where combined with other materials, principally brick, ensuring not only better chances of protection from the elements but giving the interiors with their soaring concrete roofs a greater sense of surprise. One extraordinary church entirely of pre-cast concrete which has been demolished, in 1996, was St Mary Magdalene and St Francis, Lockleaze, Bristol, by TH Burrough of 1956, again with an open campanile. However, the careful repair of the pioneering church at Goldthorpe, South Yorkshire, shows what can be done by a dedicated community proud of the one extraordinary building in its little town.

~~~

Recommended Reading

- TP Bennett and FR Yerbury, Architectural Design in Concrete, Benn, London, 1927

- P Collins, Concrete: the Vision of a New Architecture, Faber and Faber, London, 1959

- D Cottam, Owen Williams, Architectural Association, London, 1986

- E Harwood, England: A Guide to Post-War Listed Buildings, Batsford, London, 2003

- Incorporated Church Building Society, Fifty Modern Churches, London, 1947

- R Jeffery (ed), The 20th Century Church, 20th Century Architecture, vol 3, 20th Century Society, London, 1998

- Mac Journal One, Gillespie, Kidd and Coia, Mackintosh School of Architecture, Glasgow, 1994