The Conservation of Britain's Heritage in India

James Simpson

|

|

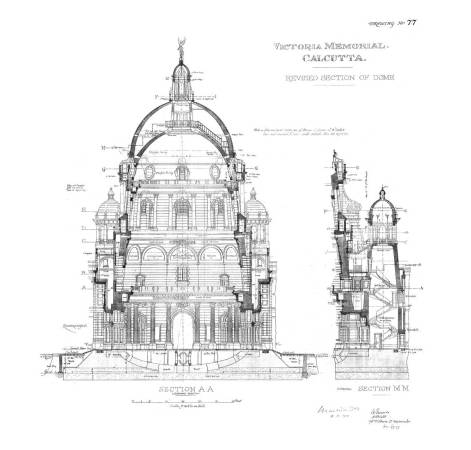

| The Victoria Memorial Hall, Calcutta: the project was instigated by Lord Curzon and the architect was Sir William Emerson with Vincent Esch as executive architect in India. Building began in 1904 and was completed in 1921 by Martin Burn & Co. |

The cultural links between the UK and India remain strong. Modern Britons tend to cringe with embarrassment when thinking of the Empire or the Raj, but this is not, in my experience, an attitude shared by most Indian professionals. The British left behind a unified democratic country that worked, as well as a cultural overlay comparable to that of the Moghuls, which is as significant to the sub-continent as the legacy of the English language.

India’s cultural heritage may be as great as that of any country in the world and the architecture of British India is now a ‘shared heritage’ of classicism, art deco, brick and lime plaster, Minton tiles and cast iron from Glasgow.

As the economy in a country of 1.25 billion people develops, this heritage is increasingly at risk, but growing prosperity is an opportunity as well as a threat. The modern conservation movement in the UK was born half a century ago: in India it is still young.

The opportunities for knowledge transfer in conservation and the potential rewards from joint working are substantial and, in the age of ‘Brexit’, we should cultivate them. Philip Davies’ recent paper, written for the Department of Culture Media & Sport, urges engagement with ‘Britain’s Overseas Heritage’: the time for this is right.

Britain’s architectural heritage in India is largely concentrated in cities like Bombay, Madras and Calcutta (now officially renamed Mumbai, Chennai and Kolkata, although their old names are still in popular use), and in the hill stations like Shimla. Lutyens’ New Delhi is well known, but the public buildings, churches, banks and warehouses and, perhaps most of all, the ordinary street architecture of all the major cities make a fine legacy indeed.

A great deal of this heritage is in a severe state of decay. This is perhaps particularly true of Calcutta, which was the capital of British India from 1690, when it was founded as the East India Company’s trading station on the Hooghly River, until 1911 when the capital was moved to Delhi. Calcutta continued to thrive as a centre of trade and commerce until its separation from East Bengal (now Bangladesh) in the mid-20th century. Since then, not helped by 35 years of communist state government, it has declined. The architectural legacy of Calcutta, a city of 4.5 million people, makes it one of the world’s great historic cities. Only last year, our own secretary of state for international development, Priti Patel, proposed to West Bengal chief minister Mamata Banerjee that it should be awarded world heritage status.

In a scheme initiated by Sir Bernard Feilden and supported by the Charles Wallace India Trust, Indian architects have been coming to the UK to study conservation through what are now Master’s degree courses at York – originally at the Institute of Advanced Architectural Studies, another Feilden initiative with Patrick Nuttgens – and, more recently, in Edinburgh and elsewhere. The development of India’s conservation movement has largely been fuelled by these architects and by a handful of homegrown initiatives. In Rajasthan, for example, the energy of Faith and John Singh – creators of the Anokhi chain and of the Jaipur Foundation – put traditional culture and heritage tourism at the heart of the state economy, and in Bombay much was achieved through the work of the late Shyam Chainani, one of the great pioneers of conservation in India.

|

|

| Britain’s architectural heritage in India includes public buildings, churches, banks and warehouses but ordinary street architecture forms an important part of this legacy too. As shown here, much of it is now in a severe state of decay. | |

|

|

| Vines emerging from the Scottish Church Collegiate School, North Calcutta (Photo: Ashish Sharan Lal) | |

|

|

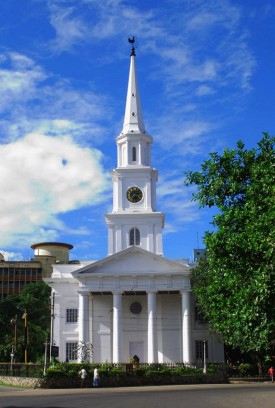

| St Andrew’s, Dalhousie Square, Calcutta: built in 1815 for the Church of Scotland, the church’s ‘spire over portico’ formula follows that of James Gibbs’ St Martin in the Fields in Trafalgar Square, London. (Photo: Rangan Datta) |

Among leading UK-trained conservation architects in India who are well known here are Vikas Dilawari in Bombay, Benny Kuriakose in Madras and South India, Gurmeet Rai in Delhi and especially in Punjab, Aishwarya Tipnis and Gaurav Sharma in Delhi and North India, Manish Chakraborti, and Nilina Deb Lal and Sharan Lal in Calcutta and East India. All maintain British connections and all work to maintain international standards of conservation, often against considerable odds.

Current arrangements for protection are in their infancy and there is, as yet and in general, little public understanding of, or support for, conservation. To quote Vikas Dilawari:

Government-owned public buildings, which are major landmarks in our cities, suffer from ill-informed, ad hoc and unwanted repairs. Even worse, privately-owned and tenanted residential buildings suffer from zero maintenance, partly due to the Rent Control Act, and since no repair is carried out, these structures dilapidate and are increasingly under threat from redevelopment. There is a complete lack of patronage and, as a result, no good craftsmen. Cheap alternatives to good work are always preferred. We, unlike colleagues in the West, have to struggle all the time. We have to be lucky enough to find good clients, who understand and appreciate craftsmanship: only then are we able to find and train the craftsmen.

The conservation process, as it has been developed in the UK over the past 50 years, is not yet understood in India and it is in this area and in the development of trade skills, that there is a great UK contribution to be made. A new campaign – CAL, ‘Calcutta’s Architectural Legacy’ – led by the distinguished writer Amit Chaudhuri is now mobilising opinion in the city, very much as the amenity societies and SAVE did so many years ago in the UK. Perhaps surprisingly, the leaders in the promotion of ‘shared heritage’ are the Danes, whose work in the former settlement of Serampore, including the restoration of the Lutheran church of St Olav, is directly supported by the Danish Government, with Copenhagen architect Flemming Aalund and York-trained Manish Chakraborti. One can only hope that where Denmark has led, the UK will follow!

Calcutta was to a significant extent a Scottish city: 40 per cent of the Europeans in the city were Scots and the links with Dundee through the jute trade were particularly strong. In 2009 a Scotland-West Bengal memorandum of understanding on matters of culture and heritage was signed by the then Scottish Culture Minister Mike Russell, but sadly, little has yet resulted from it. A new charity on the building preservation trust model, the Asia Scotland Trust (AST), is being established to support conservation in the city, in local partnerships and with advice from Simpson & Brown in Edinburgh and Alleya & Associates in Calcutta. The AST has two projects under development: St Andrews Kirk and the Scottish Church Collegiate School. Both are prominent ‘heritage buildings’, recognised as such by the Calcutta Municipal Corporation. These are being regarded as pilot projects, to be partly funded locally and partly from funds raised in the UK: and there is plenty more to do!

St Andrew’s was built in 1815 for the Church of Scotland, on a prominent site in Dalhousie Square, adjacent to the Writers’ Building, which is now the seat of the government of West Bengal. Like its namesake in Edinburgh’s New Town, its ‘spire over portico’ formula follows that of James Gibbs’ St Martin in the Fields in Trafalgar Square. Its traditional flat ‘Indian Terrace’ roof, finished with lime concrete and jaggery (a traditional waterproofing admixture made from sugarcane[1]), was replaced in the mid-20th century with an ‘agricultural’ pitched roof of lightweight steel trusses and corrugated asbestos-cement sheets, with galvanised steel gutters. Both the design and the materials of this roof have failed badly and are no longer able to cope with the monsoon rains. The project is to replace the roof and to restore the ceiling of its fine classical interior.

The Scottish Church Collegiate School was established in 1830 in Beadon Street, North Calcutta by missionary Alexander Duff for the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. Duff was an influential figure and one of those – with Raja Rammohun Roy – credited with the vital decision to make English the language of education and administration in India. The handsome classical building, built like most of Calcutta from brick and lime plaster, is in very poor condition externally; the central stairs are barely safe, and improvements are badly needed. The project is for a comprehensive programme of repair and restoration and of such improvements as can be achieved, including recreational use of the terrace roof and a new fire escape.

Another project examined by the AST is the repair and restoration of Duff College, also established by Duff, but for the Free Church of Scotland (which broke away from the established Church of Scotland following the ‘Disruption’ of 1843). This impressive structure, standing prominently in Nimtala Ghat Street and fronted by giant order Doric columns, is now in a disastrous state of decay, collapsing internally and with trees sprouting from every opening. It has been the subject of a long campaign by architect Nilina Deb Lal – currently completing doctoral research in Edinburgh on Calcutta’s construction – and may now be taken on by the West Bengal Heritage Commission.

VICTORIA MEMORIAL HALL

The greatest and most spectacular of the British buildings in Calcutta is the Victoria Memorial Hall (VMH), built as a museum to commemorate the ‘Queen-Empress’ following her death in 1901. The instigator of the project was Lord Curzon and the architect was Sir William Emerson, then president of the RIBA, with Vincent Esch as executive architect in India. Building began in 1904 and was completed in 1921 by Martin Burn & Co, a company which still exists.

The VMH was built on an ‘H’ plan in a European classical style, with Moghul touches, and Emerson’s choice of white Makrana marble facing was a deliberate reference to the Taj Mahal: memorial to Shah Jahan’s favourite wife Mumtaz. A large statue of Queen Victoria stands at its centre and the great dome above is topped by a 3.5 ton gilded bronze Angel of Victory, modelled by Lindsey Clark and cast in Edinburgh by George Mancini. This revolves in the wind and is known locally as ‘the fairy’.

The Victoria Memorial is headed by its secretary and curator, governed by trustees under the chairmanship of the governor of West Bengal, and is ultimately the responsibility of the government of India. Despite being such a powerful symbol of the Raj, it is much loved and admired by Calcuttans and by Indians in general. It is widely recognised as:

- one of the world’s great buildings in its own right

- an architectural set-piece in an open and highly formal garden setting, which contributes powerfully to the wider landscape of the city

- one of the great museums of the world and, as such, a building in need of change to accommodate the 21st-century needs of collections, exhibitions, staff and its large number of visitors. Its recent history is presented here as a case study: one which, unfortunately, tends to confirm Vikas Dilawari’s observation that ‘government-owned public buildings which are major landmarks in Indian cities, suffer from ill-informed, ad hoc and unwanted repairs’.

To the ordinary observer, the VMH appears to be in good condition. However, concerns began to be expressed in the 1980s and Sir Bernard Feilden, then director of the International Centre for Conservation in Rome (ICCROM), was invited to inspect and report on its condition. His 1992 report described the problems he observed and made recommendations.

|

|

| One of the 877 original drawings which aided the 2012 fabric inspection |

Despite being essentially a mass brick structure, the building includes a lot of steel which supports the floor and flat roof structures, while cables contain the outward thrust of the dome at its base. Sir Bernard noted extensive water penetration and expressed concern about corrosion and expansion of the steel. Some of the very clear recommendations in his report were taken up, but many were not and 15 years later concerns were again being expressed.

In 2007 I was asked to undertake a further and more detailed inspection. This was eventually done in 2012 through Dulal Mukherjee & Associates on instructions from the National Building Construction Corporation (NBCC). I was assisted by John Sanders (Simpson & Brown) and Ashish Sharan Lal (Alleya & Associates), with structural input from Michael Beare of AKS Ward Lister Beare.

The process followed the standard pattern for fabric inspections. Every exposed surface and visible feature was examined and evident defects and symptoms, large and small, were recorded. These were then correlated and analysed in order to establish an understanding of the soundness of the original materials and construction, and the mechanisms of decay. The task was then to draw general conclusions, to ascertain the need for further invasive investigation and to make recommendations for further action, including conservation work. A secondary object was to identify opportunities as well as problems, including the potential for integrating repair work with alterations designed to improve the operation of the building as a museum and visitor attraction. The task was greatly assisted by the availability of no fewer than 877 original drawings which described the construction in great detail.

The report which followed the 2012 inspection made reference to the ‘significance-based’ approach to conservation derived from The Burra Charter, and emphasised that conservation was the management – not the prevention – of change. It emphasised that international good practice required that repair and restoration work and work to accommodate necessary change should be carefully planned and managed in an integrated way. It also made clear that the report itself was not a specification and that further investigation, appraisal, cost assessment, prioritisation, design and specification would be required before any programme of work could be responsibly put in hand.

The principal conclusions of the 2012 report were that:

- there was significant water penetration through the roof surfaces, parapets, cornices and open joints in the marble facings; in addition, approximately one in five of the rainwater pipes was leaking

- there was very high humidity in the accessible under-building voids and significant condensation on the underside of the steel-supported principal floor, with evidence of rust staining; most of the under-building was inaccessible for inspection

- the steel roof and floor structures were corroding to a significant extent; embedded steel in the foundations and the cables in the dome were also likely to be deteriorating; this deterioration was progressive and could only be arrested by drying the building

- further investigations, including access to the remaining voids, and action to eliminate leaks and condensation should be initiated as a matter of urgency

- the mechanical and electrical services were seriously deficient, poorly installed and affected by moisture

- the flat roofs should be made more completely and effectively waterproof, insulated and given a reflective upper surface to minimise solar gain

- ground moisture should be kept out of the fabric and a dry, air-conditioned space created in the under-building voids beneath the principal floor; as first suggested by Sir Bernard Feilden. This would provide the opportunity to create new accommodation for the ancillary functions that a modern museum requires – as at the Louvre, the National Gallery of Scotland etc. It would also enable the temperature and relative humidity in the main galleries to be more effectively controlled

- the revolving mechanism of the Angel surmounting the dome should be serviced.

By far the most serious concern, raised by Sir Bernard as long ago as 1992 and strongly reiterated in 2012, was water penetration and its likely effect on embedded structural steel. Specific recommendations for next steps were made, including advice that further investigative work should be planned as a matter of urgency in order to develop a strategic approach and a carefully prepared and fully integrated 5-10 year programme of work. More than three years have now passed since submission of this report and there has been no indication that this strategic proposal for an integrated programme of work has been prepared. Such concepts are hard for bureaucracies to grasp and things move slowly in India.

|

|

| Above left: interior of the Victoria Memorial Hall with Thomas Brock’s statue of the young Queen Victoria. Above right: condensation glistening on the underside of the principal floor of Victoria Memorial Hall, and corrosion to the steel beams supporting it. | |

LOOKING FORWARD

It is clear that conservation is not yet a priority in India, except where sites like the Taj Mahal and the cities of Rajasthan are of obvious benefit to the tourist economy. This is particularly true of old towns like Shahjahanabad (Old Delhi) and Patiala – both the subject of visionary reports by Sir Patrick Geddes, written in the 1920s – and of the cities and hill stations like Calcutta and Shimla, where the shared heritage of Britain and India are concentrated. Taken as a whole, India’s cultural heritage may be the richest in the world, but the realisation that it is a massive asset which requires management has yet to be fully appreciated. As the economy grows, the risks that much of it may be lost increase by the year.

Nor is the physical heritage the only area of concern. Much has been done by the UK to train a new generation of conservation architects: the challenge now is to establish an understanding of proper process and to equip the cities in particular with the trade and craft skills essential for good repair and restoration work. The experience built up here over the past 50 years makes the UK uniquely well-equipped to extend the concept of ‘shared heritage’, to build on the foundations laid by Sir Bernard Feilden in the 1970s, and to strengthen further the historic relationship between Britain and India through conservation.

NOTES

[1] Bureau of Indian Standards, IS 3036:1992 Code of Conduct for Laying Lime Concrete for a Waterproofed Roof Finish, New Delhi, 1992