Dating Old Buildings

Frank Kelsall

|

|

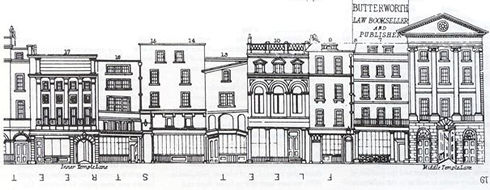

| Two buildings in Fleet Street, the former Union Bank by George Aitchison Sr of 1856 and the former Legal and General Insurance Office of 1885 by Sir Robert Edis. These are dated by illustrations in the Illustrated London News and the Builder and by documentary research in the bank and insurance companies' archives. |

The office of the Ancient Monuments Society is in a delightful small Edwardian building (listed Grade II), in an alley just south of St Paul's Cathedral. The date, function and architect are not difficult to establish for the building has its former use, as 'St Ann's Vestry Hall', inscribed on the frieze and the more eagle-eyed can spot a stone at low level marked 'Banister Fletcher & Sons, Architects, 1905'. Dating a building by inscription is a long tradition, though few name the architect in such brief form as that on the Town Hall at Blandford Forum which reads 'Bastard, Architect, 1734'. The trouble with inscriptions, useful though they are, is that you cannot be sure that they are right (many have been added by later owners) or that they date more than a particular feature or phase of development. The datestone has to be treated with the same critical eye as the rest of the building.

Historic buildings need historians. That might seem axiomatic, but surprisingly few of the half million or so listed buildings have ever been thoroughly investigated. The rise of a specialist role of architectural historian has gone hand-in-hand with the growth of the conservation movement over the last half-century. What do architectural historians do? How can they contribute both to an understanding of architecture of all periods and to the selection of what we should seek to conserve? Architectural historians find out about buildings; who built them and when; what they were for; how they have been altered and take the form they do now; what people and events have been associated with them. They assemble evidence and interpret it. Dating is an essential first step.

Those who listed historic buildings for many years worked to the acronym DAMPFISHES, later BDAMPFISHES. 'D' for date, 'A' for architect, 'M' for materials and so on. The primacy given to date was preceded in later years only by a 'B' for a brief description of what sort of building the list description covered. As the listing criteria set out in Government guidance PPG15 show, the older a building is, the more likely it is to be listed. Date is inevitably crucial to any understanding of a listed building.

|

|

| The same street frontage as shown in Tallis's London Street Views of 1847, showing surviving earlier timber-framed buildings and Thomas Hopper's insurance office, built 1838 and demolished 1885. |

Generally speaking, the older the building, the more likely it is that dating will have to be by comparison with other known and dated examples. The traditional typologies developed by architectural historians, especially for timber framed vernacular buildings, are now being given greater precision by dendrochronology.

The mouldings on stonework on the other hand remain a matter for comparative analysis alone. Such details provide a rich source of information. In London for example, a plain 18th century terrace house can usually be dated to within five or ten years simply by looking at it with an informed eye. Furthermore, there are rich documentary sources from which, in much of London north of the river at least, it is possible to date a house even more accurately.

|

|

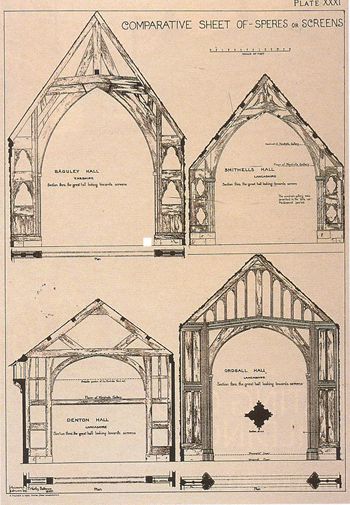

| Survey drawing for Henry Taylor's Old Halls in Lancashire and Cheshire, 1884, showing comparative sections through four spere trusses |

In many cases an approximate date can be given after a first inspection. There are clues in storey heights and the relation of these heights to ground level, in window spacing, in roof form and pitch, in plan and the position of chimney stacks as well as in the architectural detail.

Although published some 20 years ago, J T Smith's guide On the Dating of Houses from External Evidence is still a most helpful guide. His more recent study, English Houses 1200-1800: The Hertfordshire Evidence (1992), has an excellent discussion of the difficulties which many buildings present; from the antiquarian copyist who makes his building look older than it is, to the enthusiastic revealer of the timber frame who removes most of the physical evidence of his building's history by stripping it back to the original.

Historians always like to confirm a date suggested by the physical evidence against any available documentary sources. At one time this was regarded as almost unnecessary, but the revolution brought about by Howard Colvin's A Biographical Dictionary of English Architects 1660-1840 has changed the nature of post medieval architectural history. From the first edition, published in 1954 to the thoroughly indexed third edition, published in 1995, we have been able to locate dates and architects quickly and to find the references to back them up. There are later biographical dictionaries but (except for a notable local attempt in Suffolk) none provide such comprehensive lists of works.

Colvin, of course, includes only buildings known to have been designed by architects. Major buildings are usually easy to date. The Builder, now Building, established in 1843, is one of many architectural periodicals that deal with buildings of a later date than those covered by Colvin.

The great advantage of documentary research is that it gives more than a date: it provides information about the building process; how the design evolved; how the building has changed since first built and for architectural history on a wider front, how the building was used and by whom. All this complements the information derived from the building itself.

|

|

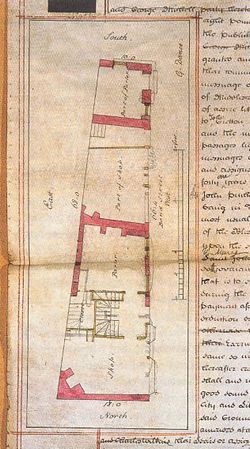

| A plan from the Corporation of London's archives, attached to one of their leases, with a plan as in 1796 and pencilled changes made before the next lease in 1810. The plan is signed by George Dance, not as architect of the building but as surveyor to the City Corporation. |

Before launching straight into primary research it is sensible to see what is already known and what might be available. The statutory list is often itself a help. It should give an analysis of how a building has developed as well as a description. More recent lists often include a bibliographical note, useful in identifying articles in Country Life or local journals and sometimes references to The Builder or other primary sources. Few lists are as detailed as that for Barrow-in-Furness where many entries give dates and attributions from the local building act plans. Then there is Pevsner, of course, the inimitable series of county by county guides to the buildings of Britain.

But the absence of a reference does not mean that none exists. More research now can be done via the Internet, with useful websites at the British Library, Historical Manuscripts Commission and the National Monuments Record. The NMR with some three million photographs and 50,000 measured surveys should always be tapped. But in many cases it is the local library and record office which is the principal source; here, in addition to topographical works and the Victoria County History there will be the journals of local antiquarian societies and other printed works.

When trying to establish a date from primary sources it is often easiest to work backwards. Map evidence can be crucial and the Ordnance Survey is always the best place to start, comparing the various editions. Some industrial areas have had very large scale maps made of them which give the plans of churches and public buildings as well. Earlier maps vary in quality and usefulness; it is always important to remember that a building shown on a site does not necessarily mean that it is the building that is there now. Working backwards through street directories and ratebooks can also tell you when a building first appeared and gaps in the series, or significant changes in value, can be a clue to alterations and rebuilding.

Owners may have title deeds and these should be examined. Some areas have had land registration since the 18th century (of these, Middlesex and West Yorkshire are the best known), but the registers are not easy to handle. For most of that part of London which used to be in Middlesex, original building leases should be registered, a source profitably tapped by the Survey of London, that Rolls-Royce of architectural surveys. Where land was owned by one of the great estates - the Crown, aristocratic landlords, corporate bodies - then with luck the estate records will survive, now often in a local archive office, or, for the Crown Estate, at the Public Record Office. Locating these records is often something with which the National Register of Archives can help.

|

| The early Ordnance Survey maps, especially those of industrial towns at 1:1056, are full of detail. This map of central Manchester in 1849 shows the ground plans of St Anne's Church and the branch Bank of England (both still there) and the Cross Street Chapel and the old Town Hall (now both demolished). |

|

| Many people live in speculatively built houses but few speculative builders sold by catalogue. This is one of the grander houses on the Eltham Park Estate built by Archibald Cameron Corbett, first Lord Rowallan, and advertised in his catalogue of 1913. |

What architectural historians like to find, of course, are drawings and illustrations. There are many topographical records and photographs. These will not necessarily help to date a building, though they may establish limits before or after which changes have taken place. As antiquarian interest in old buildings developed, this changed the nature of drawings from that of 'seats', as in many county histories, to that of rchitectural record, as in the huge collection of some 12,000 drawings produced by the Buckler family and now in the British Library. Further into the 19th century more archaeological drawings were produced.

All such drawings need to be assessed carefully. A recent study of JS Crowther's drawings of Cheshire churches has shown that he doctored them to fit his preferences for what the churches should have looked like and it is known that TH Shepherd, usually a very reliable topographical draughtsman, removed existing accretions from a drawing of 1851 to 'restore' the terrace to its Palladian symmetry of 1738.

Most drawings were not produced for artistic, antiquarian or archaeological purposes but for practical reasons, at the time of building or subsequent alteration. These are often a better clue to the date of a building than the topographical illustration. They can range from beautiful perspectives, designed to attract the patron and critic, to the technical detail of working drawings. The greatest collection of design drawings is that of the Royal Institute of British Architects in the British Architectural Library, now being merged with the archive of the Victoria and Albert Museum. Otherwise designs can often survive with clients, in family or corporate collections.

Not all designs were carried out, in full or in part, but the unbuilt is often as fascinating as the built, as shown in Unbuilt Oxford or London As It Might Have Been. For Victorian and later buildings designs were often published in architectural magazines such as The Builder (for which there is a splendid published illustrations index for 1843-1883) and the British Architectural Library's 'grey books' are an important guide to published illustrations of 20th century buildings. When searching for illustrations and contemporary descriptions, however, the relevant trade literature can be as important as the architectural. A brewery might appear in the Transactions of the Institute of Brewing or a hotel in the Caterer and Hotel Proprietors Gazette.

The process of dating, like all other research into architectural history, is interactive between the building and the documents. Each helps interpret the other. It is the architectural historian's job to work at this interface and join other professionals in formulating proposals for what should happen to historic buildings. Recent Heritage Lottery Fund guidance on conservation plans has emphasized the importance of research and understanding in drawing up plans, and this is paralleled by the advice in PPG15 that applicants for listed building consent should show that they understand their buildings. How this is done is perhaps less important than that it should be done and done well.