Early and Vernacular Door Fittings

Linda Hall

|

Figure 1. Elegant medieval drop handle with highly decorative back-plate at St Mary’s Church, Lenham, Kent. Handles like these are usually fixed directly to a latch which lifts as the handle is turned (see Figure 2). Note the thin metal backplate and small nails/nail holes which clearly distinguish original 17th century and earlier designs from later imitations, and the original hand-made nails in the door. | ||

|

Figure 2.This typical 17th century latch is fastened directly to a drop handle on the other side of the door. The two split ends of the rod which connect the handle to the latch can be seen protruding through the hole at the pivot point on the left, where they have been turned over to grip the latch. Note the incised saltire cross and line decoration. | ||

|

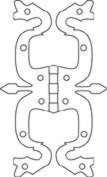

Figure 3. A 17th century ‘vertical’ door handle at St Wenna’s church, Morval, Cornwall which typifies one of the most common designs found in countless farmhouses all over the country. Note the saltire cross decoration. |

Fixtures and fittings are vitally important in enabling an old property to retain its character. Early vernacular fittings in particular have a unique charm and interest that is the product of their manufacture, their style and ornamentation, and their age. Their removal or replacement by inappropriate reproductions gives an immediate modern or fake feel to a house, even if its walls and roof are hundreds of years old.

Early door and window fittings were

forged by hand from wrought iron by the local blacksmith and fastened

with hand-made iron nails. Wood was also sometimes used for door

handles, latches and latch fasteners. There are hundreds of variations

to the basic designs used and, being hand-made, each one is unique.

DOOR HANDLES AND LATCHES

Door handles have two basic forms, the 'drop' handle (Figure 1) and the 'upright' handle. Drop handles are fastened through the door to the latch on the other side by a flat piece of iron. This fastener operates like a split pin, passing through the back-plate, through a hole in the door and then through the latch itself where the ends are splayed (Figure 2) so that a slight turn of the handle lifts the latch off its catch. Drop handles are almost certainly older than upright handles; many church doors retain medieval examples. They were used until the late 17th century in vernacular houses and the heavy loop of the handle was usually formed into either a simple but elegant stirrup or a heart shape. Back-plates are often highly decorative in the medieval tradition with delightful symmetrical patterns, usually either circular or

diamond shaped.

Vertical door handles, commonly referred to as either Norfolk or Suffolk latches, can take a variety of forms. The simpler one consists of a handle of flat section with the ends expanded into decorative plates by which it is fixed to the door (Figure 3).

It is not known when this design was invented, but it is common throughout the 17th century and for much of the 18th century. The later examples have very large leaf-shaped ends. Some vertical door handles incorporate a large rectangular back-plate, often highly decorative, with a handle of roughly circular cross-section forged to it.

Both types of vertical handle operate the latch by means of a thumb-plate attached to an iron bar which passes through the door and raises the latch. This mechanism has also been seen in wood in a house in Guernsey and in others in East Sussex.

The usual decoration on the handle itself is a single or double indentation around the centre, but some examples are decorated with simple patterns of incised lines such as the 'saltire' (X-shaped) cross, as at Morval Church in Cornwall (Figure 3). More elaborate handles usually indicate a late 18th, 19th or 20th century date.

The latch consists of a horizontal bar held in a vertical loop, with a latch fastener attached to the door frame. Old latch fasteners sometimes survive even when the original door has been replaced, but are often overlooked. Latch fasteners can be quite decorative; some 17th and 18th century examples have twisted shanks and spearhead ends.

Figure 4

|

|

||

| a) A wooden latch and handle at La Maison du Haut, St.Pierre-du-Bois, Guernsey. Note how the latch-lifter is neatly tucked behind the door handle on the right. | b) A more typical wooden latch and handle dated 1729, Surrey. Reproduced by kind permission of the Council for British Archaeology. |

Latches are frequently decorated with an incised saltire cross at the end, sometimes with vertical lines on either side, and the supporting loop may also be decorated with tiny chamfers and nicks. The pivot end of the latch is generally a spearhead or round shape but may be more elaborate. Some latches are more complex altogether, with a decorative back-plate and a spring mechanism. In the 18th century it is common to find wrought-iron latches fixed to a plain rectangular back-plate and operated by a brass knob handle. Some have an iron spring, and may incorporate a bolt. More sophisticated 18th century houses have brass drop handles and a more modern type of mortise latch contained within the door.

Wooden latches and latch fasteners

are almost impossible to date; the design may go back to medieval

times but it is unlikely that any existing ones are older than the

17th century and many may be a good deal younger. The type was very

popular in the Arts and Crafts movement (see Figure 4). They could be operated

either by a string or thong passing through the door above the latch,

or by a finger-hole below. In Sussex a wooden lifting bar is common,

and a variety of other mechanisms are occasionally found. Some doors

also have a wooden handle used to pull the door to, consisting of

a plain or decorated rectangle projecting from the door at an angle.

Strap hinges are one of the more prominent forms of ironwork and the ends were often delightfully ornamented in the vernacular manner, the most common designs being a spearhead, a double scroll or heart, and a fleur-de-lys (illustrated below), but some were plainer. Many examples survive from the medieval period onwards.

Figure 5

| Typical vernacular door furniture details on the front door of a farm in South Gloucestershire, dated 1676. | ||

|

||

| Note how the elaborate detailing to the exterior contrasts with the simple detailing inside: fleur-de-lis hinges wrap around the door and are looped over the simple iron pintels inside before being fastened back on the door; the elegant drop handle with a quatre-foil back-plate on the outside, plain latch behind; studded vertical boards on the outside, fastened to plain horizontal boards on the inside. |

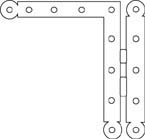

Most of the earlier strap hinges were hung by a loop of each hinge on an iron pintle (a simple L-shaped spike) set into the door jamb (the post or frame on which it is mounted). The loop was formed either by turning the end of the hinge back on itself or by wrapping it around the end of the door. From the 17th century the T-hinge was also used for internal doors; it is fixed to the door frame by a vertical base-plate which can be a plain rectangle (late 17th century onwards) or may have a more decorative form (up to about 1675). In the 18th century a very standardised form of T-hinge was used, which tapered to an extremely thin neck with a small round end. Although of a standard design, these were still hand-made and contrast with the much more regular 19th and 20th century mass-produced T-hinges which usually have a simple rounded end.

Smaller hinges were used for lighter

internal and cupboard doors (see Figure 6, diagrams d, e and f). The most decorative is the cockshead

hinge, in use in the Elizabethan period and the first half of the

17th century. A simplified form occurs in a Surrey house of 1656,

and there is some evidence to suggest that the type returned to

favour in a debased form in the 18th century. H-hinges are common

in the late 17th and 18th Centuries; 17th century examples usually

have decorative ends, later ones are usually plain. A variant is

the very common L-hinge or HL-hinge, used for internal doors in

the late 17th and 18th century. Most are plain,

but some have shaped

ends. Butterfly hinges are particularly common on small cupboards,

especially from about 1670 into the 18th century, but some may be

earlier. Occasionally both small cupboard hinges and larger door

hinges combine a strap hinge with a base-plate which is like half

a butterfly hinge.

| Figure 6 | |||

Above: A strap hinge with lozenge decoration on the front door of a house in Pucklechurch, South Glos dated 1624. Like many, the hinge passes beneath the moulded fillets |

a) b) |

Left: Typical 17th century strap hinges. Drawings reproduced by kind permission of the Council for British Archaeology.

Below (left to right): L-hinge, H-hinge and Cockshead hinge

|

|

|

|

|

|

Other types of door furniture include knockers, bolts and key-plates. Door knockers (illustrated below) can be similar to drop handles, but are more often round and are usually positioned so as to knock on a strap hinge or on one of the iron nails holding the door planks together. There are also various types of long knockers, some with a decorative back-plate.

Key-plates can be very elaborate or a simple lozenge shape; 18th century examples are generally smaller and simpler and on internal doors are often brass. Locks are usually enclosed in a simple timber case.

Bolts survive from the 16th century, if not earlier, and can be either round or rectangular in section. The latter often have a saltire cross on one or both ends. Bars, loops or knobs are used to operate the bolt, and some have elaborate mechanisms to ensure that they cannot be withdrawn from the outside. The bolt fits into an iron hasp on the door frame. Where the door has been changed, surviving hasps will usually seem unduly large, as doors of this period fitted against, not within, the door frame; the hasp therefore has to allow for the thickness of the door as well as the size of the bolt.

Early bolts are fastened to the door by individual iron hasps, either square or flat in section. From the 18th century, bolts often have a back-plate with integral hasps and guide-pieces. These developed into the standard 19th and 20th century mass-produced items.

17th century door knockers Long

knocker with back-plate

|

Baluster-type

long knocker

|

|

Round

drop knocker

|

Spur

knocker

|

All window and door fittings, if genuinely old, will show wear and irregularity; the iron is often quite thin and the nails usually unobtrusive. Victorian and later features, by comparison, tend to have thicker iron, prominent fixings (often screws, but sometimes would-be 'hand-made' nails which are far too regular), and more elaborate decoration. Particularly deplorable are the modern reproduction iron hinges and latches which have a falsely irregular surface that is supposed to look like genuine ageing.

This is not true of the Arts and Crafts features; they have a genuinely hand-made look, but often use several different types of decoration on one item, where the originals would have used one or two. Some of their items look as 17th century ones would have looked when new; the design is right, but simply lacks ageing.

Today, where new fittings are required to match surviving originals, it is generally accepted that the Arts and Crafts approach suits the character of these vernacular buildings. Original techniques of design and manufacture may be used, but no attempt should be made to match the patina of age artificially, not only because faked finishes confuse the history of the building, but also because a poor fake casts doubt on the authenticity of originals also.

Bear in mind that designs vary from one fitting to another; replicating one design throughout a house would be wrong. Churches often retain many early fittings which are similar and often identical to those used in local houses. The later items are often dated, so they can be a good source of reference for 17th and 18th century material.

Recommended Reading

- James Ayres, The Home in Britain; Decoration, Design and Construction of Vernacular Interiors, 1500-1850, Faber and Faber, London, 1981

- Stephen Calloway (Ed), The Elements of Style: An Encyclopedia of Domestic Details, Mitchell Beazley, London, 1991

- Linda Hall, Fixtures and Fittings in Dated Houses 1567-1763, Council for British Archaeology, York, 1994

- Gertrude Jekyll and Sydney R Jones, Old English Household Life, Batsford, London, 1939, rev 1944-45

- Hugh Lander, House and Cottage Interiors: The Do's and Don'ts, Acanthus Books, Redruth, 1982

- Nathaniel Lloyd, History of the English House, 1931, The Architectural Press, London, 1975

- David and Barbara Martin, Domestic Building in the Eastern High Weald 1300-1750, Part 2: Windows and Doorways, Hastings Area Archaeological Papers, Robertsbridge, 1989