A Spiritual Enterprise

Douglas Strachan's Stained Glass in the Memorial Chapel, University of Glasgow

Nick Haynes

|

|

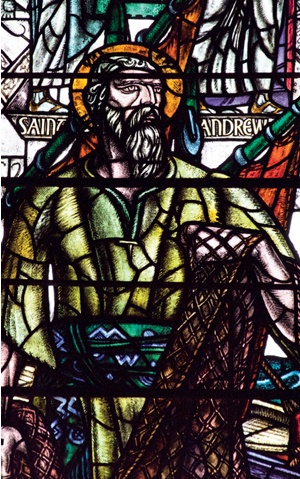

| St Andrew (west window, light 1, 1931-7), gifted by Dr James Thomson Bottomley in memory of William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin, a professor of natural philosophy and chancellor of the university in 1904-7 (All photos: Nick Haynes, reproduced by kind permission of the University of Glasgow, unless otherwise stated) |

The University of Glasgow moved from the city’s polluted High Street to George Gilbert Scott’s academic citadel on rural Gilmorehill in 1870, but the partially finished complex lacked a chapel.

The renowned architect of the Edward VII Galleries at the British Museum, John James Burnet, began planning the completion of the western quadrangle of Scott’s great edifice with a new arts block and chapel in 1913. However, the outbreak of the first world war in 1914 put a stop to all building projects, and it was January 1923 before work could begin. On 4 October 1929 the ailing principal, Sir Donald MacAlister, finally dedicated the chapel to the memory of the 750 university staff, students and alumni who perished in the Great War.

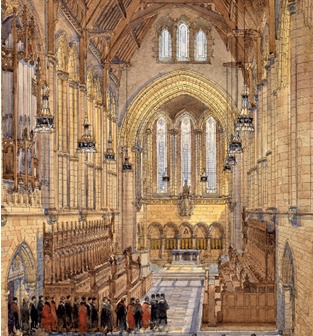

Burnet looked to 13th-century France for the Gothic inspiration of his design, and perhaps to the surviving medieval chapels of the universities of St Andrews and Aberdeen for character, scale and details. For the beautiful Arts and Crafts interior of the chapel, Burnet planned an open-trussed roof, oak choir stalls and organ case, stone sculptures, marble memorial panels and a scheme of stained glass windows.

In November 1919, Burnet consulted the stained glass artist Douglas Strachan (pronounced ‘Strawn’) about an early version of the chapel design and obtained estimated costs for the window series. Strachan and Burnet were both members of the Aberdeen Ecclesiological Society, founded in 1886 by Dr James Cooper, former Minister of St Nicholas, and from 1899 the professor of ecclesiastical history at Glasgow.

Cooper is thought to have been instrumental in securing Strachan’s first two commissions for the university in the ceremonial Bute Hall: the Robert Story Memorial Window of 1907-9, and the Janet Galloway Memorial Window of 1909-14. Strachan also worked on the east window of the Burnet-designed Stenhouse and Carron Parish Church in 1914.

A ‘harmonious scheme of stained glass windows’ was still on the agenda of the New Building Committee when it met in March 1927. Unfortunately, the university’s budget did not stretch to finishing the sculptural scheme or installing stained glass at the outset, so the slender lancet windows were filled initially with a simple pattern of leaded clear glass supplied by the Abbey Studio of the City Glass Company, Glasgow.

Principal MacAlister’s health was failing by the autumn of 1929, and he was clearly keen to complete the architectural legacy of his period in office by securing Strachan’s services for the Memorial Chapel windows. On 10 October 1929 MacAlister suddenly announced that he would retire five days later. Just one day before he stepped down, the Chapel Committee authorised Sir Donald to consult again with Strachan about designing a complete scheme for the chapel windows that could be implemented as funds allowed.

Unaware that MacAlister was no longer in post, Strachan replied enthusiastically on 16 October 1929: ‘Ten years of constant demands for windows far in excess of the number I could undertake, may have robbed the letter post of some of its earlier power to thrill in this way: but the Complete Extensive Scheme with its superb possibilities is a thing apart, and always sends the blood to one’s head – pleasurably’. Thus began an extraordinary commission that was to occupy Strachan on and off until his death 21 years later.

|

|

||

| Above left: detail of Strachan’s ‘Tanks, Machinery of War’ window at the Scottish National War Memorial, Edinburgh (Photo: Antonia Reeve, reproduced by kind permission of the Trustees of The Scottish National War Memorial). Above right: design for the Memorial Chapel interior c1928, John Burnet, Son & Dick, watercolours added by Robert Eadie (Reproduced by kind permission of the University of Glasgow) | |||

Born in Aberdeen in 1875 and educated at Robert Gordon’s, Strachan attended evening classes at Gray’s School of Art while working as an apprentice lithographer, then studied at the Life School of the Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh in 1894-5.

After a stint as a political cartoonist on the Manchester Evening Chronicle in 1895-7, Strachan returned to Aberdeen as a mural and portrait painter before finding his passion for stained glass in a commission for St Mary’s Chapel of the historic Parish Kirk of St Nicholas. Among other commissions in the city, Strachan also worked for the University of Aberdeen at King’s College Chapel and at the library of Marischal College on the John Cruikshank memorial windows, which celebrated the faculty of science through the theme of creation.

By 1929 Strachan had gained an international reputation through the publicity surrounding his four huge windows of 1911-13 at the Peace Palace in The Hague. He also had significant experience of designing complete schemes, such as the Lowson Memorial Kirk in Forfar of 1914-16, and war memorial windows including those of 1923-7 for the Scottish National War Memorial at Edinburgh Castle.

|

|

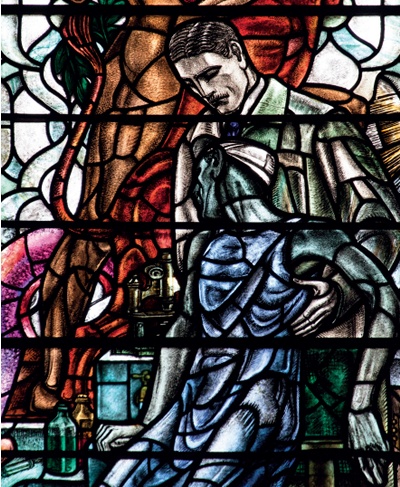

| ‘Medicine’ (window 4, north wall, 1934-5), in memory of Sir Donald MacAlister: ‘the basic idea of the image as a whole is “Health-Energy set against Suffering-Exhaustion” … I have purposely planned the composition so that the doctor may seem to be easing the Sufferer’s movement down, or up – in accord with the spectator’s mood at the moment’ (Douglas Strachan, November 1934) |

Although the university’s Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery holds only one preliminary design or ‘cartoon’ relating to the chapel windows (the Alma Mater window), the university archives contain an extensive correspondence between Douglas Strachan and Principal MacAlister and his successors, Robert Rait from late October 1929 and Hector Hetherington from 1936. These letters are remarkable for the light they shed on Strachan’s creative processes and the evolution of an exceptional series of artistic works.

Strachan studied the chapel carefully to capture its ‘personality’ and the ‘local or community tang’, observing the light at different times of day and noting various practical bearings on the scheme so that the new windows could ‘look as if they had grown there naturally and inevitably’.

Although Principal MacAlister had initially suggested an Old Testament theme based on Hebrews 11, his successor Robert Rait was keen to allow Strachan freedom to select the best treatment for the space and not impose artistic restrictions. Eventually, after a period of illness, Strachan sent a key plan with notes and estimates to Principal Rait in December 1930.

In this document Strachan set out the defining principles of his scheme as ‘an attempt to figure man’s life, all life, as engaged on a spiritual enterprise: to visualise our little planet moving on through infinite space – or perhaps one ought now to say Finite Space, whatever that may mean: man’s unceasing search and endeavour to comprehend the universe and his own spiritual aspirations, and to find one image for both’. His note continues with a more detailed description of the arrangement of the windows:

Planned in sections this gives for the 12 lights in the N. & S. Walls. The Universe, creation of Solar system, earth, man: symbolised by the Signs of the Zodiac (subject-matter of the “bosses” in the 6 N. wall windows: 2 Signs to each boss: the “Days” or stages of creation (in the corresponding position on the S. wall): and below these in the full length lights eight figures (one in each light) typifying the various domains of man’s thought and search (and therefore the work of Universities)

N.

Theology, Law, Medicine,

Applied Science

S. Philosophy, Literature and Arts, History,

Science

Or any other group deemed more representative: these forming a connecting passage between: History: the daily life of the community in the West Window, and Revelation: a kind of Benedicte window with Spirit dominating: East.

The cost of each window was set out in the note, with £700 each for individual lancets, £235 for the four small part-lancets in the nave, £5,200 for the four-light west window and £3,600 for the three-light east window. As can be seen from the pricing, Strachan intended to give greater elaboration to the main east and west windows. He estimated that it would take two years to clear his workload before a start could be made on the chapel commission.

|

|

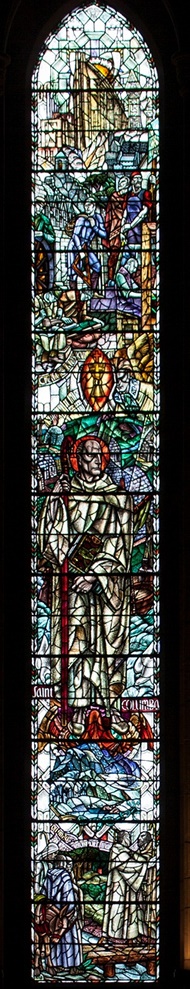

| St Columba (west window, light 2, 1931-7), gifted by Lady Mechin. |

Strachan worked from his house, Pittendreich, in Lasswade, Midlothian, which had been designed by David Bryce in 1857 and specially adapted by Sir Robert Lorimer in 1928-9 to accommodate Strachan’s glass studio and kilns. A number of assistants were employed, who were allocated cottages on the small estate.

The decorative elements of the windows were closely interwoven with the subject matter, as in the Scottish National War Memorial windows where there are similar motifs and themes. The jagged or curvilinear shapes of the painted glass panes are emphasised by their leaded surrounds, and along with the varying intensity and pattern of colour they cleverly provide a sense of movement or emotion to the distinct zones of the windows.

There is no narrative structure as such but the windows are organised internally into themes. For example in the great west window, the saints occupy the central zone of each lancet, while scenes from history are placed at the top and bottom. Signs of the zodiac are located in the top zones of the nave windows, with contemporary figures representing the various branches of knowledge below.

With the exception of the representations of ‘Alma Mater’ and Charity, all the principal figures are male. Although Strachan never completed the chancel windows, he planned to emphasise the shrine-like appearance of the communion table and memorial tablets.

The University Court, led by Principal Rait, welcomed Strachan’s proposals and set about finding donors for each of the windows. Numerous potential donors were approached and by April 1931 seven windows were promised.

The first of the windows to be commissioned was the rose window in the west wall, which was dedicated in memory of the late university chancellor, Lord Rosebery, on 21 February 1932. Strachan explained to Principal Rait that ‘as a rose window should be rich and jewel-like, I have allowed myself a slightly larger proportion of rich colour in this window than will be permissible in the others’.

The scheme then progressed along the north wall of the chapel, with Aries and Taurus, Gemini and Cancer, Applied Science and Theology dedicated in 1934 and Medicine in 1935. The chancel arch windows and the Alma Mater window in the choir gallery followed in 1937.

Lights 1 (St Andrew) and 2 (St Columba) of the four-light west window were finally dedicated in October 1937, some six years after the initial designs were submitted. It is clear from his correspondence that they presented Strachan with the most complicated technical problems of his career to date: ‘The effect I sought has proved maddeningly elusive at times and before I got it I must have made, smashed, and remade the equivalent of four windows’.

Strachan also undertook considerable research in order to make the historical details as accurate as possible. The Philosophy window also caused Strachan much anxiety, which delayed it to the point that the donor withdrew his offer in 1939.

At the outset of the second world war, the two completed panels were removed from the west window of the chapel for safe storage in Edinburgh, alongside the windows of the Scottish National War Memorial.

In spite of the restrictions and wartime gloom, Robert Rait’s successor Principal Hetherington instructed Strachan to proceed with the final two lights of the west window: St Kentigern and St Ninian. These were completed relatively quickly, by April 1941, but also placed in storage for the duration of the war, this time in Strachan’s old doocot at Pittendreich.

The whole scheme for the great west window first came together in the chapel at the dedication of the St Kentigern and St Ninian lights on 3 December 1945.

Although Strachan had produced designs for the other windows, and discussions continued between Strachan and Principal Hetherington throughout the 1940s, these were to be his final contributions to the decoration of the chapel. Other stained glass artists completed the programme in a variety of styles in the 1950s, 60s and 70s.

‘You once expressed the hope that I “would give you something as good as the S[cottish] N[ational] War Memorial window scheme”. With a scheme such as the proposed plan submitted herewith I can quite definitely promise you something better’. These were Strachan’s words to Principal Rait in December 1930. Sadly, Strachan only lived to finish nine of the projected 18 windows in the Memorial Chapel at Glasgow, but his genius is amply displayed in these outstanding examples of the art of stained glass.

~~~

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the assistance of Elizabeth Cumming, Lesley Richmond (Archivist and Deputy Director of the Library, University of Glasgow), Stuart MacQuarrie (Chaplain, University of Glasgow), Elizabeth McCrone (Head of Listing, Historic Scotland), Shona Elliott (Curator for Documentation and Fine Art, University of Aberdeen Museums), Vanessa Stephen, Margaret Taylor, and Nigel Wallace.

Recommended Reading

A Carruthers, The Arts and Crafts Movement in Scotland: A History, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2013

P Cormack, ‘In Praise of Douglas Strachan (1875-1950)’ in The Journal of Stained Glass, vol XXX, BSMGP, London, 2006

E Cumming, Hand, Heart and Soul: the Arts and Crafts Movement in Scotland, Birlinn, Edinburgh, 2006

M Donnelly, Scotland’s Stained Glass – Making the Colours Sing, The Stationery Office, Edinburgh, 1997

J MacDonald, Visions Through Glass: The Work of Douglas Strachan, Crawford Arts Centre, St Andrews, 2002

D Macmillan, Scotland’s Shrine: The Scottish National War Memorial, Lund Humphries, London, 2014

AC Russell, Stained Glass Windows of Douglas Strachan, 3rd edition, Pinkfoot Press, Balgavies, 2002