Sacred Space

Liturgy and Architecture at Durham Cathedral

Allan Doig

|

|

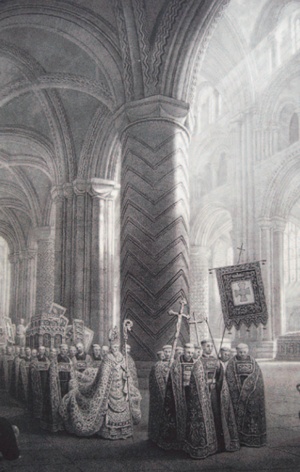

| ‘The Interior of Durham Abbey; with a Procession of Monks on one of their Grand Festivals Previous to the Reformation’, E Nash, 1828 (Cathedral Library, Durham) |

Medieval liturgies in the English church were often very mobile. Processions would move through a sequence of interconnecting spaces in and around the church or cathedral. On great occasions they ranged further still, visiting parts of the town, other churches and even surrounding fields, which were blessed on Rogation Days prior to the harvest. The example of Durham Cathedral demonstrates that the local saint and the liturgy as it was adapted to his cult, were determining factors of the architecture that developed around his shrine.

Durham Cathedral was built as the final resting place for the relics of St Cuthbert. It is hardly surprising then that the reputation of the saint and aspects of the cult that was established around his relics, defined the cathedral’s architecture and patterns of spatial organisation and use. The Rites of Durham [1] is an essential source for exploring the origin and development of the cult, its geographical location and the sequential architectural response to its ceremonial, liturgy and social structure.

The Rites of Durham survives in a number of variant manuscripts, the oldest of which seems to have been written just before 1600. It has every mark of being a first-hand account in great detail by someone who knew the fabric of the cathedral intimately and was close to the ceremonial, the official structure, and the individuals involved. He looks back with great sympathy and fondness, but without theological or political comment. By the time it was written, the world it described had been swept away. The author records some of the early losses to the fabric as a result of reforming zeal, but the overall architectural arrangement has survived remarkably intact. The use of and relationships between the spaces and the sacred precincts have changed radically: a point demonstrated by the fittings and furnishings, and the treatment of the patron, St Cuthbert.

Cuthbert died on 20 March 687 and was buried on Holy Island in St Peter’s Church in a feretory (a shrine holding the saint’s relics) a little above the pavement on the left side of the altar. He had great powers of discernment and healing in life, and his body remained an existential connection with the saint, now among the whole company of heaven. Continuing miracles, described by Reginald of Durham in his Libellius de admirandis beati Cuthberti virtutibus, proved that the saint’s power endured. A late 12th-century manuscript that was probably Reginald’s own autograph copy is kept in the cathedral treasury. When Cuthbert was disinterred 11 years after his death he was found ‘whole, lying like a man sleeping, being found safe & uncorrupted & lyeth awake, and all his masse clothes safe & fresh as they were at ye first hour that they were put on him’.[2]

In 875 he was again disinterred when the monks fled before Viking incursions. The community entrusted with the care of these sacred relics was defined by that task and their ‘Exodus’ experience which lasted 120 years until, while trying to return with the body to Chester-le-Street where they had sheltered before, the bier on which the saint was borne became fixed to the spot. After fasting and prayer to determine what this meant, the bishop and the community had a revelation that the body should be carried to Dunholm, a hill (or ‘dun’) on an island (or ‘holm’; ‘Dunholm’ gradually evolved into the modern ‘Durham’). His last resting place was miraculously revealed to them and a temporary shelter of wattle was built. Then ‘the Bishop came with ye corpse and with all his [strength] did worship’.[3] The cult was now permanently located on a protected and virgin site, divinely revealed. The bishop then began work on:

a mykle [little] kirk of stone, and while it was in [the] making from ye Wanded kirk or chapel they brought ye body of that holy man Saint Cuthbert: & translated him into another White Kirk so called, & there his body Remained [four] years, while ye more kirk was builded, then the Bishop Aldun did hallow ye more kirk or great kirk so called before ye kallends of September, & translated Saint Cuthbert’s body out of ye white kirk into ye great kirk as soon as ye great kirk was hallowed to more worship than before.[4]

|

||

| ‘The North Prospect of the Cathedral Church of St Mary & St Cuthbert at Durham’, J Harris, 1727 (Cathedral Library, Durham) |

It seems improbable that Cuthbert’s body was moved from the wattle church (which even then appears to have had a stone tomb for the saint) into a ‘White church’ (implying stone) for four years before being translated into the greater stone church at its consecration on 4 September 998.[5] Different interpretations are compatible with the text of the manuscripts.[6] Whatever the finer details of that sequence, however, there is no doubt that the sanctity of the relics and the established liturgy of the cult of St Cuthbert dictated the fundamental characteristics of the architecture from its precise location to its size and material. Only the most important of buildings at this date were of stone, so if there was an intervening smaller church of stone, then this was a sequence of utmost significance.

In the new abbey church, completed in 1020,[7] Cuthbert’s shrine was on a broad pavement elevated ‘[three] yards high, being in a most Sumptuous & goodly shrine above ye high altar called ye fereture’.[8] This raised pavement recalled the first feretory in St Peter’s Church on Holy Island. Bishop Cosin’s Roll manuscript continues, describing the saint’s tomb in the cloister,[9] ‘when he was translated out of the White Church to be laid in the Abbey Church’, resulting in multiple sites for veneration. Cosin goes on to describe a carved and painted stone effigy of the saint, with mitre and crozier ‘as he was accustomed to say mass’, placed above the tomb which was enclosed by a wooden screen. This created a miniature church, recalling the first one of wattle which had received Cuthbert’s body on his miraculous arrival. That resting-place had been sanctified and memorialised at what was either another temporary resting-place for Cuthbert’s reliquary or had possibly been Cuthbert’s shrine in the Saxon Cathedral.[10]

The structure, in any event, remained in the garth (a garden enclosed by a cloister) until the Dissolution, near the door where deceased monks were carried for burial in the garth. The monks thus made a journey similar to Cuthbert’s, passing the same sanctified place, in the hope of the same final destination in heaven. In this monument, the long Exodus and the miraculous designation of its end is called to mind in order to bring out the full significance of the saint’s tomb. Processions to the monument and to the tomb or high altar were, then, redolent of the memory of that extraordinary Exodus experience. The high altar was just to the west of the intended final tomb, so the mass, which joined the worship of the community with the worship of heaven, was reinforced by the relics which were the existential connection with the saint who continued to intercede on their behalf in the courts of heaven.

|

||

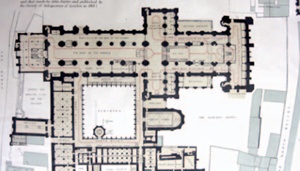

| Plan showing the ancient arrangements according to existing remains and other evidence [Based on the Ordnance Survey 1/500 Plan (1860), and that made by John Carter and published by the Society of Antiquaries of London in 1801]’, WH St John-Hope, in Fowler’s edition of Rites of Durham |

The monumental structure in the cloister stood until the Dissolution when Dean Horne caused it to be demolished and its material given over to his own use. He had Cuthbert’s effigy set against the cloister wall. Dean Whittingham had it defaced and broken up to remove all trace of the cult of saints. Whittingham believed in the sanctity of the Word, not of places, spaces or things, and this major theological shift in the notion of sanctity would cause a similar shift in the patterns of use and focus of the architecture.

The radical nature of this shift can hardly be exaggerated; Cuthbert’s presence had defined the community from before his death on Lindisfarne. He was a constant presence with them, their patron and protector, interceding for them and working miracles. The whole of the life and miracles of the saint were shown in a set of windows running all the way from the south door into the cloister right to the door to the new cathedral. These too were smashed during the reign of Edward VI by Dean Horne.[11]

Clearly, during the medieval period, sacred space hallowed by the presence of the saint was to be found both within and outside the church. The cloister was hallowed ground, a place of ceremony and prayer. It was in this eastern part of the cloister where, on Maundy Thursday, 13 poor men had their feet washed by the prior and were given 30 pence along with food and drink. Daily after eating, the monks would proceed through the cloister into the garth where they would say prayers for their departed brethren buried there. They would then return to the cloister for study until evening prayer.

Bishop William Carileph, Prior Turgott and Malcolm King of Scots (as chief benefactor) laid the first stones of the new cathedral in 1093, and when the choir was complete in 1096, Bishop William ordered that the Saxon building completed by Bishop Aldwin should be pulled down. Bishop Cosin’s manuscript recounts how William went to Rome in 1093 to get a licence from Gregory VII to remove the lazy Canons and replace them with Benedictine monks from the twin monastery of Jarrow and Wearmouth. William died two years later and was succeeded by Ranulf Flamberd as Bishop.[12]

|

||

| The Central Tower viewed from the Cloister (Photo: The Chapter of Durham Cathedral) |

Long before the cathedral was finished, probably with the completion of the eastern arm in 1104,[13] Cuthbert was translated into his new tomb, ‘a faire and sumptuous shrine about three yards from the ground on the back side of the great Altar which was in the east end of the quire, where his body was solemnly placed in an iron chest’. This feretory was in the original apsidal east end of the Norman cathedral, the shape of which has been archaeologically well established.

On the arrival of Bishop Richard Poore from Salisbury in 1228 a new eastern termination was projected, resulting in the Chapel of the Nine Altars, completed in 1253. These architectural changes transformed the pattern of use for this most sacred area of the cathedral. Pilgrims and their circulation routes had to be separate from those of the monks who were constrained to total celibacy; altars had to be separated from the laity; the relics had to be securely protected; and peculiarities of the local rite were to be suppressed.

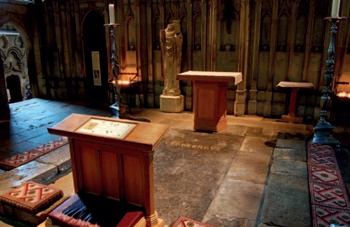

The nine altars were ranged each in its own bay and separated by panelling with storage for all the supplies, vestments and objects for use there. Everything was at hand for the reverent celebration and reservation of the sacrament, and for the final ablutions. The iconography of the space, though it is not a tightly coordinated scheme, is established by the dedication of the altars and related stained glass in the windows above.[14] With its grand new setting, the now square feretory of St Cuthbert was continuously embellished with jewels and gifts from pilgrims. The tomb itself in the feretory was:

estimated to be one of the most sumptuous monuments in all England, so great were the offerings and Jewells that were bestowed upon it; and no less the miracles that were done by it, even in these latter days;… And at this feast [St Cuthbert’s Day, 20 March] and certain other festival days and at the time of divine service they were accustomed to draw the cover of St Cuthbert’s shrine… and the said rope was fastened to a loop of Iron in ye North pillar of ye feretory having six silver bells fastened to ye said rope; so as when ye cover of ye same was drawing up ye bells did make such a good sound that it did stir all ye people’s hearts that was within ye Church to repair unto it and to make their prayers to God and holy St Cuthbert; and that ye beholders might see ye glorious ornaments thereof.[15]

The aural interconnectedness of the spaces was important: the sound of the bells on the shrine’s mechanism rang out through all the spaces of the cathedral prompting prayers in response and, when the shrine was accessible, visits to see the splendid offerings. Lord Neville, for instance, after victory in battle, brought the banner of the King of Scots and a captured holy cross as well as jewels for a thank-offering to the saint.

Cuthbert was a powerful patron and all the sacred activities, ceremonies and liturgies were carried out with reference to places hallowed by his presence and the iconography of his life and works. Candles held aloft on the ironwork of the feretory lighted the liturgies celebrated on the nine altars; the main objective of the pilgrim was access to the feretory, but as an alternative, the monument of his former resting-place in the cloister was also acceptable; the cloister saw ceremonies of foot-washing and monk’s funeral processions passing that same monument; finally, the high altar, for the grandest of liturgies, was hard up on the west side of the feretory. Above the high altar was a pyx (for the reserved sacrament) in the form of a silver pelican feeding her young with the blood of her own breast, as an image of Christ’s sacrifice.

|

||

| The feretory of St Cuthbert (Photo: The Chapter of Durham Cathedral) |

Separating the high altar and the feretory was the magnificence of the Neville screen. Architectural separations, however grand, between these sacred spaces were visual by degrees, not aural separations, so their texts and chanting and petitionary prayers were overlapping and interwoven in simultaneous, although differently geared, cycles of monastic and lay worship. It was not perfectly integrated, but was rather all-embracing. The great processions took the host, relics, crosses and banners round all the spaces of the cathedral and on great festivals they went out into the town linking other churches into the liturgy as well.

The rites swept sacred objects, sacred spaces and sanctified people into a great cycle of worship and praise and thanksgiving, united with the saints and the whole company of heaven. The author of the Rites had seen it all pass away, fondly recording his vivid memories before they too were extinguished with his aging generation. The Reformation seemed to have effaced this grand and dignified unity of liturgy and architecture, but during the 1620s and 1630s, John Cosin, first as Prebend, then after the Restoration as Bishop of Durham, began to recover some of the lost glory. He was owner of one of the manuscripts of the Rites of Durham and had a good deal of sympathy for the old ways.

With the Reformation, a defining chapter had closed for the liturgy and architecture of Durham, as it had throughout England. Nevertheless, successive adaptation of both the liturgy and the architecture, including the involvement of ‘Wyatt the Destroyer’,[16] Sir George Gilbert Scott and the cathedral’s modern rebranding as a World Heritage Site, all provide fascinating insights into a local distinctiveness tempered by broad national similarities.

~~~

Recommended Reading

John Crook, The Architectural Setting of the Cult of Saints in the Early Christian West c300-1200, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 2000

Joseph Thomas Fowler (ed), Rites of Durham: being a Description or Brief Declaration of all the Ancient Monuments, Rites, & Customs belonging or being within the Monastical Church of Durham before the Suppression, 1593, Surtees Society Publications, Durham, 1903

Arnold Klukas, ‘Durham Cathedral in the Gothic Era: Liturgy, Design, Ornament’, in Artistic Integration in Gothic Buildings, Virginia Chieffo Raguin et al (eds), Toronto University Press, Toronto, 1995

Acknowledgements

This article is a foretaste of a longer essay that will be published in 2012 as part of a new book on Durham Cathedral edited by David Brown, a professor at the University of St Andrews and previously professor and canon at Durham. I am indebted to many in the cathedral for their help including Canon Rosalind Brown; Alastair Fraser, Gabriel Sewell, and Catherine Turner in the Cathedral Library; Andrew Gray in the Archive and Special Collections; and Ruth Robson, the Events Coordinator.

Notes

1 Published in 1903 by the Surtees Society in a

critical edition by Canon Fowler showing the

variations (see entry in Recommended Reading)

2 Roll, c1600, in Rites of Durham, p63, (English

quotations have been largely modernised).

The coffin made for him in 698 is in the Treasury.

The lid is carved with an image of Christ in

Majesty surrounded by the four Evangelists; the

end has the earliest English representation of the

Virgin and Child.

3 Ibid, p66

4 Ibid, p66-67

5 Crook, p167, n40; and Roll in Rites, p68

6 On this confusion see also the note in Rites, p249

7 Rites, p72

8 Roll in Rites, p67, & MS Cosin, c1620, pp74-75

9 Modified by MS Hunter 45

10 Crook, pp168-9

11 Roll in Rites, pp76-77

12 MS Cosin, p73

13 Crook, p168

14 For a detailed description, see MS Rawle 1603, in

Rites, pp118-22

15 MS Cosin, interpolation from H 45, c1655, in

Rites, p4

16 Georgian architect James Wyatt (1746-1813), who

earned a reputation for over-zealous ‘restoration’

work at the cathedrals of Salisbury, Hereford and

Durham