Early Joinery

Primary techniques and influences in furniture construction from the 11th to the 16th century

Neil Stevenson

|

|

| The Hungerford chapel at St Julian’s, Wellow near Bath gives a glimpse of how colourful churches once were. The rood screen, coffered ceiling and wall paintings are believed to date from c1443 when the chapel was furnished. The screen is delicately decorated with fine tracery, but the carving is rough compared to later work. Its colour scheme, which was restored in 1952 by W Caroe, is similar to an example in Exeter City Museum of the same period, and is likely to be a faithful copy. (Photo: Jonathan Taylor) |

Historic churches were once packed with fine wooden furniture, both free-standing and fixed. Although few early pieces have survived, churches provide a rich insight into the development of furniture construction since the Middle Ages. Rather than a steady refinement of principles and techniques, this has been an ad hoc process driven by a range of factors. Providing a history of furniture from the rudimentary techniques of the medieval period to the more sophisticated methods of the 16th century is not straightforward. Regions with different local economies and infrastructures developed at different rates. This resulted in the crudest forms of construction being used concurrently with more sophisticated techniques. Closely linked economic and cultural centres naturally developed more quickly and shared new fashions.

In secular and ecclesiastical contexts alike, social factors were key: the upper echelons of society sought to assert their status, and the rich sought to display their wealth. The height and decoration of a piece of furniture was an index of its owner’s social standing. As a result, decoration and structure developed throughout the Middle Ages, with form heavily outweighing function.

CONSTRUCTION

Plentiful timber and an abundance of unskilled labour, meant that labour-intensive methods of construction were prevalent among the earliest furniture makers. Furniture such as the dug-out chest was hugely impractical, being very heavy and unstable (though many parish churches retain examples dating from the Norman and even early medieval periods). It was later improved by better hollowing techniques, giving chests more regular sections. This reduced weight but increased the likelihood of structural failure. Metal bands resolved this somewhat but introduced the new issue of adverse reactions between iron and oak.

Socio-economic advances inevitably fuelled changes in furniture design and construction. An important factor was the improvement of living conditions, with dwellings becoming warmer and, more importantly, drier, which required timber with greater stability. This was resolved to a degree by a move to planked construction, which gave a more consistent material and would ultimately allow further development once the challenge of moisture content had been overcome. In the meantime, heavy cross rails and iron bracing reduced movement in boarded structures.

Joinery skills became a recognised force in furniture construction during the 13th century with the first examples of clamped fronted chests. Their design used a long mortice and tenon to join wide uprights to a wide panel at right angles to them and between them. Although a step forward, this technique could not rectify the problem of material shrinkage and movement in wide boards.

|

|

||

| Above left: the ornately carved Easter Sepulchre at St Michael’s Church, Cowthorpe, Yorkshire is believed to date from the 14th century, and was almost certainly originally painted in bright contrasting colours. Chests like this were once common, playing a key role in the ritual of Easter week (Photo: Brian Coleman). Above right: a 12th century replica of a treasury chest made for Dover Castle in oak with decorative iron reinforcing bands held in place by double clenched nails (Photo: Paul Lapsley). | |||

The breakthrough for cabinet construction was the development of ‘panel and frame construction’, which started to appear in England around 1400. In this type of construction the board remains loose within a frame but is secured by a groove. This allows considerable movement in either direction before any deformation of the structure occurs. The technique enabled the development of complex panel designs and layouts, as well as larger structures. Solid timber construction has changed little since this point, with all structures being controlled by the requirement for expansion and contraction. Elements not suitable for frame and panel construction were tamed by an adaptation of it. A table top, for example, could be held in grooves in the underframe by shaped blocks called buttons, which allowed flexibility.

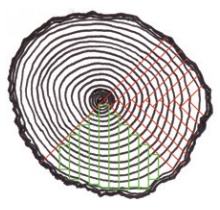

CONVERSION AND AIR DRYING

The development of large saws and sawpits

provided more consistent material of

different thicknesses than could be achieved

by splitting logs with wedges, and narrower

planks

allowed the timber to dry more quickly

and evenly. However, the material from

split logs was inherently more stable than

the majority of regular sawn material when cut through-and-through (see diagram).

This led to the introduction of new sawing

techniques which sought to maximise

quarter-sawn material, where the annual rings

run near to vertical when viewed from the

plank end. This did not prevent deformation

but, once coupled with improved drying

techniques, it did manage to control it.

|

|

| Quarter-sawn timber: two methods of converting quarter sawn timber are shown above, in red and green, both producing boards with the grain generally at right angles. It is a labour intensive method of conversion, but produces the timber least prone to warping and cupping. (Drawing: Jonathan Taylor) |

Air-drying is a simple technique still used today. Planks are stacked flat with spacers between boards. The stack is set above ground level and then covered to protect it from rain and sunlight. The timber then gradually equalises with the surrounding environment as it dries. This process also ensures that the competing stresses within the material are slowly released, providing a very stable board for further crafting. The ability to manage timber moisture content by controlled air-drying led to a quantum leap in joinery techniques. Timber became more predictable, allowing a new level of finesse in detailing.

TURNING

The development of turned components had an immediate impact on furniture, creating interesting forms out of otherwise purely functional sections. Inevitably, elements began to be added that were purely decorative.

The craft of turning has a very long history

(the first recorded guild was in 1295) and provided a great range of items in addition to

furniture components. The turned and bored

joint gave rise to furniture that was striking

if not entirely practical. The popularity of

turning as a decorative feature has

continued

unabated with each century developing its

own styles and techniques in combination

with other decorative features and finishes.

TOOLS

It is no coincidence that furniture quality improved in line with the development of metals that could take a keener edge giving greater accuracy to finer details. While tools have evolved dramatically, the basic functions were established early on and the medieval tool kit would not be alien to today’s craftsman. Where tool development has taken place it is in the range and variety of equipment. An 18th century craftsman had the choice of multiple types of chisel, saw and plane, each devised to enhance a particular technique to achieve ever finer work. The relative poor quality of the tools would not have been such an issue when working in green timbers, but the difference in working characteristics between green and dried timber is significant: dried oak in particular is very much harder than green oak. Clearly the use of more dimensionally stable air-dried timbers helped to drive improvements in tooling technology.

Other trades have also been a major influence in the drive towards improved tools. As today, conflict is a major catalyst in technological development. Weapongrade metals would certainly have found their way down to the woodworker, who would have been an active participant in the military forces of the day.

DECORATION

Early decoration was typically rudimentary but robust in execution. The deprivations of the social environment militated against fine detail except in particularly august situations, such as churches. Colour was an important element in the finer medieval furniture, with dazzling displays of gold and bright, contrasting colours. Painted furniture and joinery would have been prevalent in all ecclesiastical buildings. While most have been lost, fine examples of extravagant schemes occasionally do survive, as at St Julian’s, Wellow near Bath.

Limited by tooling and green timber, early decorative carving was minimal, although geometric chip carving was a regular feature. More refined work began to appear in the 14th century. As wood carving techniques developed, the specific trade of carver established itself and restrictions on the type of work a joiner could undertake were introduced. This demarcation meant that furniture with relatively naive decoration continued to be produced alongside the flamboyant work of specialist carvers.

|

|

||

| Above left: a chip-carved roundel on a reproduction 12th century oak storage chest with iron locks and hasps. Above right: For the reproduction 12th century furniture at Dover Castle the timbers were hand planed using blades to achieve the uneven, hand hewn finish of medieval carpentry. (Both photos: Paul Lapsley) | |||

Lines scratched into rails and stiles formed the earliest decoration. This developed to include edge details of chamfers which were then formalised into a range of regular shapes that appeared as a formal language throughout the medieval period. Mouldings were achieved by shaping a steel plate to the counter profile required and then mounting it in a timber block or ‘scratch stock’, which could be scratched repeatedly into the timber until the shape was achieved. This technique was largely superseded by the development of stock moulding planes in the early 18th century, although it is very likely that individual craftsman would have been making their own bespoke planes from an earlier date. Stock moulding planes provided a more consistent shape and allowed for finer details.

TIMBERS

The predominant timber for most of the early period was oak, and indeed, this remained the mainstay of furniture production until the mid 20th century because it is strong, stable and resistant to decay. Until the 18th century, oak was so abundant in most areas of the country that there was little thought for conservation, and other timbers were generally considered inferior except where an understanding of particular characteristics promoted their use. Elm for example was particularly good for chair seats because of its interlocking grain, and ash for bending due to its flexibility and shock resistance.

REPLICATING HISTORIC JOINERY

When it comes to replicating historic furniture, we are fortunate that almost all of the techniques used are still practised today in some form or other; presenting little problem for a skilled cabinetmaker. But how authentic should a replication be? Is it necessary to convert the timber in a sawpit and finish the surfaces with an adze? Replications of the Henry II furniture at Dover Castle were problematic because techniques had to be used that were known to be flawed, as in the case of planked construction held together with nails.

A common failing for the modern cabinetmaker is ‘over-finishing’ a historic replication. Standards of finish beyond the visible surfaces were generally poor, so sawn surfaces should be left untouched inside and at the back of replica work. During the extensive Dover Castle project, new techniques had to be adopted to ensure that pieces had the right feel. Visible surfaces were hand planed using blades with convex cutting edges. This helped to provide a smooth but uneven surface that had the right feel when touched.