Earthen Art

The investigation and analysis of domestic wall paintings on earthen supports

Lisa Shekede and Stephen Rickerby

A fine antique-work painting at Church House Farm, Wellington, Herefordshire, partially destroyed during historic structural reconfiguration and from rainwater infiltration, demonstrating the vulnerability of paintings on earthen supports

Britain is fortunate to have a rich and varied wall painting heritage. For most, this art form is associated with the medieval murals which decorate the interiors of our churches and cathedrals, but a large proportion is made up of vernacular paintings dating from the mid-16th to the mid-17th centuries, mostly executed on earthen supports and typically found in timber-framed buildings.

Despite growing awareness of their existence and significance, such paintings remain largely overlooked and often neglected, both in terms of their intrinsic value and with respect to their unique and varied material characteristics. This latter factor means that particular approaches and methodologies are required in their conservation.

Painting Types and Themes

|

|

| Detail of a vigorously if crudely painted scrollwork frieze applied onto wattle and daub at 8 Red Lion Steet, Alvechurch, Worcestershire (All photos by the authors) |

The adjectives ‘domestic’, vernacular’, and ‘artisanal’ are difficult to avoid when describing these types of painting, but the implication that they therefore belong to a league far beneath that of high art is unfortunate.

It is certainly the case that paintings can range hugely in quality. Some are undoubtedly rudimentary, including simple decorative work carried out by artisanal workers and plasterers.

However, surprising number are executed with skill, using sophisticated techniques and high quality paint materials. Whatever their status and level of accomplishment, all bear witness to the lives, beliefs, preoccupations and aspirations of ordinary people in the intimacy of their own homes.

Although earlier examples exist, by far the majority of surviving domestic wall paintings date to between the second half of the 16th and the first half of the 17th centuries. This was a period characterised by social, political and religious upheaval, accompanied by economic change and population growth.

The survival of so many paintings from this period reflects both a boom in construction and a burgeoning class of homeowners enjoying unprecedented, if modest surpluses.

Reflecting these times of change, domestic wall paintings from this period are characterised by an enormous diversity of types and themes.

Many emulate the prestigious wall coverings which decorated (and insulated) the homes of the wealthy, including wainscoting, tapestries, embroidered (especially blackwork) hangings, and in the case of some later examples, even wallpaper.

Others reflect contemporary Renaissance tastes popularised via prints imported from Italy and the Low Countries. One design form, often called moresque painting, consists of repeated interlocking geometric designs based on a diagonal grid.

Another, superior form known as antique-work is largely monochrome and consists of largescale symmetrical designs populated by grotesque figures.

Some painting schemes incorporate figurative painting. These are often religious in theme, but unlike earlier pre-Reformation examples, they are not so much devotional as didactive and moral in purpose, consisting predominantly of scenes derived from popular stories from the parables and the Old Testament.

The main design is normally sandwiched between a frieze and a dado, the former sometimes decorated with scrollwork enclosing fanciful figures and carrying moral texts, crests and other devices.

What are Earthen Supports?

|

|

| This bold floral scrollwork design once decorated the entire room of this house in Little Stretton, Shropshire, but now only one complete panel survives, applied onto split lath and daub panelling. |

These are painting substrates derived from soils with properties which allow them to be formed into cohesive structures or plasters.

These are specifically selected from the inorganic soil strata underlying the topsoil and are frequently modified by the use of additives.

These can include aggregates with the purely physical function of adapting soil texture; fibres such as hay, straw and animal hair, which have multiple functions such as improving insulation, increasing tensile and compressive strength, reducing weight, and reducing shrinkage and cracking on drying; oils and other vegetable extractions with functions such as increasing water resistance; and materials such as chalk, ash, blood and dung, which can act in various ways as chemical stabilisers.

Although often rather dismissively described as ‘mud’ construction, the art of earth building is the result of centuries of experience and refinement in sourcing and adaptation.

Vernacular earth construction traditions in the UK include those based on load-bearing compacted earth walling (as in ‘cob’ and ‘wychert’ construction); earth-based plasters and mortars applied to masonry or brick walling; and, most commonly, wattle and daub.

The latter is a composite construction type consisting of load-bearing timber-framed structures spanned by non-load-bearing infill panels.

These have timber armatures, often of hazel wattles or split lath woven horizontally around, bound, or otherwise fixed onto vertical staves, providing a flexible support for thick applications of earth-based ‘daub’.

The daub may in turn carry one or more lime plasters or grounds. Most surviving domestic wall paintings are found in timber-framed houses, and it is common for the paintings to carry over both the timber frame and the infill panels.

An Endangered Tradition

Although a large number of timber-framed buildings survive in the UK – mainly dating from the late middle-ages to the mid-18th century – many have lost their daub infill panels (often replaced by brick ‘nogging’) and very few retain the wall paintings that once adorned them.

There are numerous explanations for their disappearance: although the extent of their susceptibility to deterioration can vary enormously depending on the nature of the soil used and the extent to which it has been adapted, all earthen supports have comparatively low compressive and tensile strength and are generally susceptible to deterioration under prolonged exposure to moisture.

Liquid water from a leaking roof or bathroom can quickly erode earthen supports and destroy organically bound paint layers, while differential hygrothermal responses in composite structures can result in a range of conflicting and potentially destabilising behaviours.

For example, environment-related volume changes in the daub support can cause stresses to painted lime plasters, eventually leading to their delamination and loss; constraints imposed on wattlework armatures by relatively static timber framing can provoke distortion and bulging, in turn causing daub and plaster to fail.

Destabilisation and loss can also result when armatures become weakened by insect attack. Paintings on earthen supports are also usually more susceptible to incidental damage than other types of construction materials, particularly given their largely domestic context.

The timber-framed buildings in which they are mainly found have also usually undergone substantially more – and more radical – modifications over the centuries than more recent buildings, including the insertion of chimney stacks, floors and staircases, and alterations to the position of windows and doorways.

By the 18th century, vernacular timber and earth building traditions were regarded as inferior and confined to the construction of poorer dwellings. The ancient timber-framed frontages of grander houses were commonly concealed behind stone or brick façades, while internally, walls and ceilings were battened out with lath and plaster or hidden behind wainscoting.

Today, most early buildings are now protected by law but the provision of practical guidance and oversight during building work is limited, and mechanisms for the prevention of unauthorised interventions are inadequate.

Often owners are unaware that the requirement for listed building consent include all alterations, inside and out. In situations where the original fabric is concealed by later lath and plaster or wallpaper coverings, it is not uncommon for wall paintings to be unwittingly destroyed during domestic renovation work.

It is also an alarming truth that earthen daubs and plasters are to this day regarded by many people, builders and homeowners alike, as an element of vernacular building which is better stripped out and replaced than retained.

For all these reasons, earthen supports remain very much at risk, and our domestic wall painting heritage continues to diminish.

|

|

| An early devotional domestic wall painting from Cothay Manor, Somerset. Cracking, bulging, separation and loss of lime plaster from its daub support are common problems. |

Conservation Considerations

Failures are often multiple and, by the time conservators become involved, condition can be catastrophic.

Treatment requirements are often major and urgent, but at the same time interventions can be exceptionally difficult to implement, often involving considerations which are not encountered in more familiar lime-based wall painting technologies.

For example, where grouting is used in a repair, the absorption of water can result in distortion, slumping and surface staining.

As light panels of earth and plaster retain water over a longer period than most other substrates, the increased weight means that the risk of collapse during or following treatment is high, especially given the low tensile strength of earthen supports.

Repairs applied too wet or using incompatible materials can cause damage to the original fabric as they shrink back on drying, and they often fail entirely.

In the long-term, differences between repair materials and the original in density, porosity and water vapour permeability can create a range of additional problems.

Risks resulting from the use of incompatible materials are also compounded when earthen supports constitute one element of a delicately balanced and easily destabilised composite structure.

Unfortunately, there is little technical/scientific research on the study of earthen support materials to guide conservators, and treatment using inappropriate materials remains the norm rather than the exception.

There remains a pressing need for accessible diagnostic tools and analytical procedures to help develop conservation practice in this area.

How Can Analysis Help?

Analysis of the Cothay Manor daub established that it was closely related to material obtained from the nearby banks of a tributary of the River Tone. Ten per cent of the daub is composed of added sand and gravels to combat shrinkage. Fibres were also added to improve the soil’s properties.

Compatibility is key, but although material for earth construction was often sourced in the vicinity of the site, soil formation processes often result in soils with radically divergent characteristics even within a small geographical area, and it is never safe to assume that all locally obtained earth can be used for making repairs.

Unless substantial fallen (unpainted) original earthen material can be recovered at the site and reused, compatibility can only be determined with any degree of accuracy through systematic examination, testing and analysis of both the original (using unpainted material) and potential repair soils.

The main types of information conservators need regarding the composition, behaviour and susceptibility to deterioration of earthen supports can be divided into two broad categories:

- those which govern the texture and mechanical properties of soil (ratios of sand-, silt- and clay-sized particles, and particle morphology)

- those which determine the chemical behaviour of soil and govern its shrink/swell potential and capacity to absorb and adsorb water (chiefly a function of the clay types present).

Laboratory testing procedures borrowed from the field of geotechnical engineering and standardised by various international organisations (such as ASTM international, the British Standards Institute and the International Standardization Organization) can provide much of the data required.

Standards are available for a large range of testing methods. Some require access to advanced analytical equipment such as laser diffraction particle-size analysers.

Others can be carried out using relatively inexpensive, portable equipment and performed, after a little practice, by the conservator.

A suite of tests including particle-size analysis (sieving and hydrometer methods) and Atterberg limits testing (chiefly plastic, liquid, and shrinkage limits) are the most useful for conservators.

Procedures are described in testing standards and manuals (see table, Earthen materials analysis resources).

The data obtained through testing can then be interpreted with reference to soil classification systems to help define the soil’s behavioural parameters, for example soil texture, plasticity, and activity, and to allow comparison of data obtained from earthen supports and potential source material for the development of compatible repairs.

Particle-size analysis comprises two stages. First, the sample is crushed lightly and wet sieved through a standard series of analytical sieves to establish the soil texture of the larger fraction.

Material passing the finest sieve comprises the silt and the clay components. This is placed in suspension in a hygrometer jar and the silt:clay ratio is determined by measuring the density of the suspension over time.

Together, the results establish the soil texture and classification of the sample. Distribution curve plotting and examination of the collected geological material allow comparison of the earthen support sample with local potential source soils and can also give invaluable qualitative and quantitative data on additives.

Plastic and liquid limits determine soil behaviour in the presence of water, specifically the amount of water required to transform it from a solid to a plastic state, then from a plastic to a liquid state.

The plastic limit is obtained very simply by establishing the moisture content of hand-rolled samples at the point at which they lose cohesion.

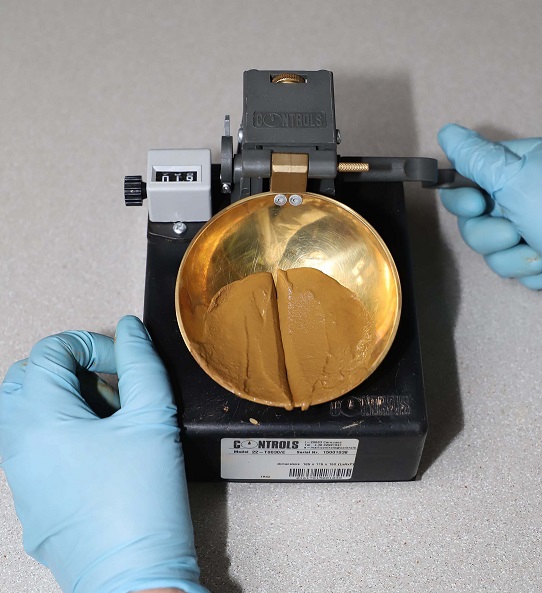

The liquid limit is obtained using a Casagrande device to establish the moisture content at which samples are unable to retain a solid form (see illustration opposite). These two tests taken together provide data which enables the ‘activity’ and plasticity index of the soil to be determined.

These parameters indicate its susceptibility to dimensional change or loss of cohesion in the presence of liquid or atmospheric moisture.

Linear shrinkage is a particularly easy and useful test which determines the two-dimensional shrinkage of the support and potential source soils.

This is done by placing a sample at around its liquid limit in a standard mould and calculating the per cent shrinkage on drying.

Detailed mineralogical information can be obtained by thin section petrography and X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) to allow more precise comparison with potential source material and to better understand the influence of the clay fraction on soil behaviour, but this is not essential.

Many accounts have been written regarding the history, development, and decoration of British vernacular buildings, but the composition and characteristics of their earthen components are still rarely given much attention.

In current conservation practice this also remains largely true, and here we have attempted to demonstrate that this deficit needs redress.

The methodology we have proposed for testing is a little complicated and time consuming, but the equipment required is relatively inexpensive, and once mastered, these tests provide the conservator with information on the nature of original materials, how they have been adapted, and which soils can be used to repair them.

It is our hope that this will encourage conservators in the field to undertake conservation of this vulnerable heritage with the rigour and sensitivity it deserves.

Earthen Materials Testing and Analysis Resources

ASTM D422-63 (2007) e2: Standard Test Method for Particle-Size Analysis of Soils

ASTM D4318-17 e1: Standard Test Methods for Liquid Limit, Plastic Limit, and Plasticity Index of Soils

BS EN ISO 17892-2:2018 Geotechnical investigation and testing – laboratory testing of soil. Determination of liquid and plastic limits

Day RW, Soil testing manual: procedures, classification data, and sampling practices, pp47–78, McGraw-Hill, New York 2001

Head KH, Manual of soil laboratory testing: vol 1: soil classification and compaction tests, pp59–95, 143–216, Pentech, London 1980

Recommended Reading

Davies K, Artisan art: vernacular wall paintings in the Welsh marches, 1550–1650, Logaston Press, Little Logaston 2008

Gowing R and Pender R, All manner of murals: the history, techniques and conservation of secular wall paintings, Archetype, London 2007

Hamling T, Decorating the ‘Godly’ household: religious art in post-Reformation Britain, Yale UP, New Haven 2010

Historic England, Wall paintings: anticipating and responding to their discovery, Historic England, London 2018

Historic England, Earth, brick and terracotta (Practical Building Conservation Series), Historic England, London 2015

Teutonico, J-M, A laboratory manual for architectural conservators, ICCROM, Rome 1988