St Eilian's Church, Anglesey

Adam Voelcker

|

|

The 12th century Romanesque tower rough-cast rendered and lime-washed and, below right, before work with drab pebble-dash on a hard cement render |

St Eilian's, situated on the north-east coast of Anglesey, is a superb example of a late medieval parish church. The tower at the West end dates from a time when this part of Wales was unconquered and far beyond the reach of Anglo-Norman rule, isolated by the mountains of Snowdonia. Its simple, solid architecture provides a rare glimpse of our Welsh Romanesque heritage. The nave and chancel are the products of later alterations made in the late 15th century, as is the separate chapel which was added in the 14th century. Internally the late 16th/early 17th century rood screen and choir stalls are also of particular importance.

Although some benches were fitted in the 19th century, the church escaped the improving hands of the Victorians, and repairs carried out in the early 20th century were made under the gentler hands of Harold H Hughes, Diocesan Surveyor and SPAB member, and co-author with Herbert L North of two charming books about the cottages and churches of Snowdonia. Under his direction the oak roof above the chapel was sensitively mended and all the roofs re-leaded in 1913. (This is known because, during the week when the 2002 SPAB scholars happened to be visiting the church, a document was found below the stripped lead stating how the lead was 'recast and relaid, a treatment which is recommended by the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings', signed by Hughes and with the names of the plumbers listed.) However, the leadwork repairs were not so successful, chiefly because the bays were over-sized, and a quinquennial inspection carried out in 1998 highlighted the need to re-lead the roofs again and to carry out some repointing to the parapets as well as a host of other less major items of work.

A grant application for the repairs was made to Cadw and later to the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) as the joint grant system which operates in England did not apply in Wales. The HLF application, an exemplary piece of work carried out by Roy Ashworth, a member of the congregation, was held up by the HLF as a model for other churches to follow, and in time, the project started on site. However, there was a considerable delay in the process because the HLF felt the scope of the repair work was not ambitious enough for such a fine church, and in consultation with Cadw, suggested that there was an opportunity to carry out further work, including the removal of modern pebbledash from the tower, complete repointing of the external walls (previously done with a hard cement mortar), re-plastering internally (which, likewise, had been repointed in cement) and, more surprising, to provide central heating, something which the church had been desperate to install but had never been able to afford.

Re-leading was carried out to the nave and chapel roofs to replace the failing 1913 leadwork. The ceiling boarding was kept in place over both areas, a vapour control layer placed on top, then insulation between new tapered battens or efirringsf, supporting a new deck constructed of plain-edged boards with gaps between, and finally Code 8 lead on a geotextile fleece underlay. Ventilation was provided to the roofs, with outlets at eaves and ridge, following details recommended by the Lead Sheet Association to avoid underside lead corrosion. One of the 1913 bays had been embossed with a date and initials, so this was re-fixed in one corner of the nave roof, and on the adjacent bay, the date and initials of the two plumbers who carried out the current work were embossed.

|

Perhaps the most contentious part of the extra work was the removal of the modern pebbledash from the tower. The construction of the tower suggests that it may have been lime-rendered and lime-washed originally, and this theory is supported by a 13th century document relating to the church which states that Gwynedd [essentially Anglesey at the time] 'glittered with lime-washed churches, like the firmament with stars'. It is known that when Sir Stephen Glynne visited the church in 1849, the tower walls were slated and they remained like this until at least 1937 when the slates began to fall off. The walls were then coated with a cement-rich render with brown pebbledash. Though ugly, it was at least keeping the tower dry. One option was to re-slate the walls, but the Diocesan Advisory Committee showed a reluctance to accept this as it might look too regular and mechanical with modern slates, and Cadw was keen to promote the lime cause.

The render option persevered, the pebbledash was removed and, once again the church, or at least the tower, will 'glitter'. The mortar used for rendering the tower is a 1:21.2 lime:sand mix, using moderately hydraulic lime from Hydraulic Lias Limes Ltd, Somerset, and coarse concreting sand from the Cefn Graianog quarry near Brynkir, Caernarfon. The mortar was thrown on in two thin (6.8mm) coats over the tower stonework, which still retained the old gritty lime mortar, and was then painted with five coats of pigmented limewash. This particular lime was used because the plasterers had had success with it previously, and in terms of environmental responsibility, it is home-produced and avoids importing. However, where it was felt necessary to use a more eminently hydraulic grade of lime - such as on the weather-facing sides of the tower spire - St Astier NHL2 (a French import) was used. The late summer weather was very changeable, so great care was taken with protection, with hessian, plastic sheeting and water spraying all used at different times and in different combinations.

Two stone pinnacles on the nave parapet were replaced with new ones. All were victims of the Anglesey maritime weather, and two in particular were in a very poor, even dangerous, condition. The original red stone probably came from Cheshire or north-east Wales, and although one or two quarries are still in operation, the masons were sceptical that stone currently quarried would be the best choice, and Cove stone from Dumfries was chosen as a more durable alternative.

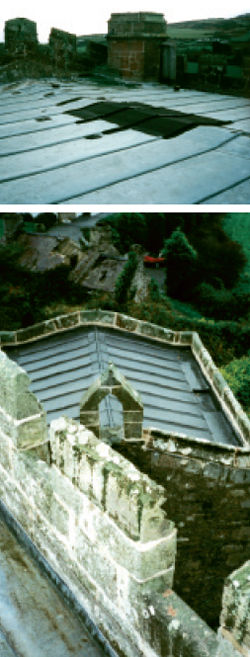

Failing

leadwork of 1913 over the nave (above) and new leadwork over

the side chapel

Failing

leadwork of 1913 over the nave (above) and new leadwork over

the side chapel |

The fine rood screen in the chancel arch (believed to be late 16th/early 17th century)  An

oak boss for the chancel ceiling, and this was replaced very

ably by a woodcarving student from the Vaynol Estate

An

oak boss for the chancel ceiling, and this was replaced very

ably by a woodcarving student from the Vaynol Estate |

An oak boss was missing from the chancel ceiling, and this was replaced very ably by a woodcarving student from the Vaynol Estate (where a school of building conservation was slowly developing). Inscribed on this boss are the initials of the main players in the project. And towards the end of the project, just when the internal limewashing was bringing the project to an end, some interesting paint surfaces were discovered in the chancel - a dark red base overlaid with coloured stencilled patterns, showing that perhaps the Victorians did make their mark after all.

Last minute research indicated that this red paint is probably Venetian red, a speciality of the former St Eilian Colour Works, an offshoot of the copper production works which had existed on and around Parys Mountain (actually a nearby hill) for centuries. When copper was found to be better extracted by precipitation than by extraction, the landscape around Parys Mountain was formed into an extensive system of ponds, each contributing to a chemical process whose end result was an ochre which could be used in the manufacture of paint. The low-grade material, which could not be used, was roasted and it is this which produced the Venetian red. When choosing a colour for the external whitewash for the tower walls, this gave a good lead, and quite coincidentally, Ty Mawr Lime, the company supplying the lime and limewash for the job anyway, was already obtaining small amounts of ochre from Parys Mountain, without realising how close the church was! The small areas of red paint behind the chancel arch have been left visible. It is unlikely that the paint continues along the south side of the chancel, since this wall was re-plastered with cement render in the recent past, but red paint may survive below the whitewash on the north side. This can be left for future generations to discover.

Heating was provided by a propane condensing boiler located in the tower and long low panel radiators tucked discreetly below the pews. A few other minor repairs were carried out in addition, but the complete re-rendering of the external walls, recommended by Cadw, was not done. Much of the hard mortar is very gritty: these areas were kept because mechanically it looked sound and the interior did not seem to be suffering unduly, but areas of smooth mortar were replaced with a 1:21.2 hydraulic lime:sand mix brushed lightly to expose the aggregate. Now that the project is finished, questions arise about how the work might have been carried out differently. For instance: when the re-leading of the chapel roof was carried out, should the original timbers have been repaired, allowing the removal of the new softwood roof which Harold Hughes so carefully threaded into the original oak structure? It was the ideal opportunity. And yet what Harold Hughes had done was a good, honest SPAB-like repair, and surely deserved to be retained as such.

Should the lead have been recast? Unlike in 1913 when it cost a mere '6 0s 0d to hire an on-site shed for casting, it would have been necessary to expend many petrol-miles in carriage to and from a suitable lead-casting firm, and this was questionable from a sustainability point of view. Was it right to carry out so much of the work recommended by Cadw and the HLF? The correct approach to conservation, surely, is to do as little as possible and only when it is necessary. But the existence of the HLF, welcome though it is to many churches, applies pressure on architects and applicants to carry out in one fell swoop a programme of extensive repairs because you only get one bite of the cherry. Peter Cleverly pointed out the danger of this back in 1977 (The Care of Churches in Change and Decay, edited by Marcus Binney and Peter Burman). He quoted John Piper, who like Morris before him extolled the virtues of 'pleasing decay' and the importance of restraint so that the patina of ancient fabric can be preserved. Piper saw the present state of a building as virtuous in itself, and Cleverly continues:

The large offer does not allow of such restraint. The one-off restoration, with its avowed intention of making all secure in every possible contingency for a long period of time, has not time to consider the very quality which causes this or that building to comfort the human spirit.Under a process of continuous care, on the other hand, mistakes can be made and mistakes can be rectified. The work that is not done this year can be done next year and the visual life of a building can develop and need not be subject to destructive shock therapy. The feeling that a historic building should be cared for as one would mend a piece of embroidery has a chance to flourish.

On a more positive note, Maintain our Heritage based in Bath, is developing and promoting a new alternative to this all-or-nothing approach to conservation. Based on the Monumentenwacht principle, which is already well established in the Netherlands, the scheme promotes continuous maintenance and sensitive repair. Let us hope that it will take hold over here.