Environmental Monitoring

Holistic and Sustainable Solutions to Conservation

Jagjit Singh

|

|

| Monitoring St George: A probe installed by English Heritage monitors variations in the relative humidity and ambient temperature of a magnificent but highly vulnerable wall painting in the castle chapel at Farleigh Hungerford near Bath. |

The deterioration of historical building materials is attributed to changes in their environment. The majority of environmental problems are associated with those defects in the fabric that lead to water penetration, condensation and dampness in the building fabric. Severe salt efflorescence, damp staining, blistering of finishes and timber decay in buildings are mainly the result of water penetration. However the causes of deterioration are also influenced by the building’s internal environment. Humidity, temperature and ventilation all contribute to this microclimate, which will vary depending upon the building structure and the envelope of the internal building fabric.

ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING

There is little point in dealing with decay if the causes of decay are not dealt with first. Indeed, it is often necessary to treat the cause alone. When dealing with historic building fabric the historic value of the original material often justifies retaining partially decayed material, provided that neither its integrity, nor that of the building of which it is part, is jeopardised in any way. Where the causes of decay are not obvious it is necessary to carry out a thorough study of the environmental conditions to identify the cause of decay. This is done by employing a range of hand-held instrumentation, physical sampling and sensor technology to monitor various parameters within the fabric of the building. Environmental monitoring may also be justified where the recurrence of a defect is unlikely to be detected before extensive damage has been caused, for example in the roof space above an auditorium. In this case long-term environmental monitoring will be required.

ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING, METHODOLOGY AND OVERVIEW OF APPROACH

The first step in the investigation of a problem building is to carry out a thorough inspection of the building for defects. Then:

- Establish moisture contents in affected materials, such as timber, plaster, masonry, insulation materials and textiles.

- Establish the humidity, temperature and dew point in the environment, both internally and externally. (The dew point is the point at which air-borne moisture condenses due to a fall in temperature, for example in a porous masonry wall which is cold on one side and warm on the other.)

- Investigate in greater detail as necessary the moisture profiles in large dimension timbers and across masonry masses.

This information can be determined by:

- Measuring moisture contents of timber with resistance based moisture meters. Probes can also be used to measure moisture contents at depth in large section timbers and those built into masonry.

- Surface moisture readings in plaster and masonry using moisture meters. These will indicate if a wall is dry but can give false readings of dampness (see below).

- Where possible, mortar samples should be taken of the areas affected to determine accurately the moisture and salt content of the masonry. This does, however, have the disadvantage of not being non-destructive.

- Data loggers used to measure the environmental parameters (temperature, humidity and dew point in particular) both internally and externally.

- Specialist probes used to measure moisture across masonry walls.

The results of all or some of the above tests will establish the cause and enable a solution to the problem to be put forward.

Mortar sample analysis

Mortar sample analysis is one of the

most important tools in establishing

accurately the moisture levels in masonry

and plasters. Where moisture levels are

high it is also possible to determine how

long there has been a damp problem

from the salt content, a high salt content

indicating a long-established problem.

Mortar sample analysis can also be

useful to determine the type of salt when

trying to establish whether there is a

genuine problem with rising dampness.

However taking samples of mortar or

plaster for analysis has the disadvantage

of causing some damage, and might

not be appropriate where, for example,

ornate plasterwork is concerned.

Timber moisture contents

Timber moisture contents above 20 per

cent indicate unacceptably high moisture

levels in the building. If this is a general

moisture level rather than a localised one then this is

likely to be associated with high humidity in

the building. Localised high readings are more

likely to be associated with a building defect.

For instance, high readings in the built-in end

of a timber would indicate that the wall was

damp, posing the threat of future timber

decay. The options are to isolate the timber

from the wall, provide an air gap around the

timber to allow the timber to breathe, or to

eradicate the source of damp and monitor the

timber as the wall dries out. The option selected will be determined according to each

situation.

Masonry moisture monitoring profiles across walls

|

|

| An example of a resistograph measurement of moisture content in timber |

Measurement of the moisture across the thickness of a wall is a specialised task as there are no instruments available off the shelf for carrying this out. Tailor-made probes are used containing hygroscopic materials (materials which absorb moisture). These are placed in the wall at varying depths and sealed off from the outside environment. After some time the probes are removed and their moisture content analysed. This method will give an indication of moisture levels across the thickness of the wall and combined with temperature and humidity readings both internally and externally will give an indication of the moisture source. However, it must be pointed out that the use of hygroscopic material to measure moisture is inaccurate at higher moisture levels.

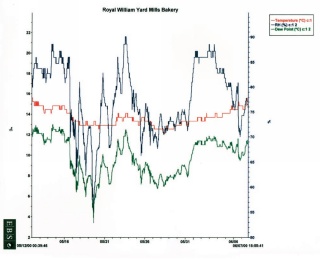

Environmental data loggers

Data loggers measuring temperature and humidity are useful to

determine whether there is, for instance, an abnormally high humidity

or whether there is a risk of condensation in a building.

If readings are taken on both the interiors and exteriors of the

building, dew points can be calculated within materials such as masonry

masses.

STABILISING THE HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT

For the holistic and sustainable conservation and preservation of historic buildings, stable environmental conditions are important.

Once investigations have been completed, a strategy can be devised to stabilise the building’s environment. Various building works may be required to prevent further water penetration and to maximise ventilation to damp-affected materials. Correction of these building defects, combined with measures to dry out the wet areas and to protect any decorative interior finishes by allowing ventilation of the wet areas, will prevent further deterioration. If thoughtfully and competently carried out, such work may extend the life of the building indefinitely and with dignity.

Until the drying out of the building fabric and its associated timber elements is completed, any other actions to remedy the deterioration problems will be ineffective and a waste of time and resources.

In some situations it may well be necessary to introduce both continuous long-term monitoring and preventative maintenance. Long term monitoring may be necessary for the following reasons:

- To provide information on the state of moisture equilibrium and balance (moisture sources, reservoirs and sinks) in the building’s environment, its fabric and its structural elements as it dries out.

- To allow co-ordination and scheduling of work stages to prioritise remedial work to achieve acceptable levels of moisture in the masonry and timber and to prevent future deterioration problems.

- To allow a cost-effective, long-term holistic approach to

environmental stabilisation of the historic environment.

~~~

Recommended Reading

- J Singh, Building Mycology: Management of Health and Decay in Buildings, Spon, London, 1994

- J Singh, 'Dry rot and other wood-destroying fungi: their occurrence, biology, pathology and control', Indoor and Built Environment, Vol 8, Number 1, p3, 1999