Reinstatement of Missing Features

Eva Palacios

THE REINSTATEMENT of missing features is often contentious. Consider, for example, a fine cantilevered stone staircase in a Georgian house which has had its original wrought iron balustrade replaced by a Victorian one. The addition has thicker cast iron sections fixed to the side of the steps, and its visual heaviness defeats the traditional floating effect of the Georgian stone staircase. In the process of repairing the house, the removal of the stair runner reveals the fixing points of the original balusters, providing evidence to allow for the original design to be reinstated. But is this appropriate? And in a listed building would the proposal be granted listed building consent?

A dilemma arises over the significance of the building: recovering the original design would be at the expense of losing part of the house’s story. Removing the Victorian balustrade would inevitably delete one of the multiple layers of history which reveal the lifetime and evolution of the building. An attempt to reinstate features belonging to a specific period runs the risk of portraying a static reality that never existed, particularly in the case of residential buildings where change could be constant due to the pressure to adapt to shifts in fashion and function. Even if architectural features from different periods might clash with the modern eye, their combination holds evidential value. Each element tells us about the story of the building through time.

The balance between the loss of evidential and architectural value can only be assessed in direct relation to the context and circumstances of each building. A different outcome would result from a different case scenario. For instance, if that Victorian balustrade were irreparably damaged, or if its weight jeopardised the structural stability of the cantilevered steps, then replacement would be justifiable on grounds of safety alone. New slender wrought-iron balusters, fixed with lead to the top of the treads, could then be considered more appropriate. The reinstatement of the Georgian balustrade would recover the spatial quality originally intended and, consequently, the harmony of the central staircase.

Llwyn Celyn: the Landmark Trust's specialists considered that its value as a 17th century farmhouse justified the removal of later features which are now exhibited on site to minimise the loss of evidential value. (Photo: John Miller, courtesy of the Landmark Trust)

Llwyn Celyn, a unique Welsh farmhouse, was repurposed as an educational centre and holiday accommodation. Grade I listed, the building’s significance incorporated a build-up layers from the medieval timber frame to its early 20th century metal frame windows, but the Landmark Trust’s specialists considered that its value as a 17th century farmhouse justified the removal of later features. The loss of evidential value was minimised by recording the existing condition and exhibiting the removed elements on-site as part of the educational experience.

The localised reinstatement of features could facilitate the better reading of distorted details. For instance, the loss of a segment within a cornice can be solved by replicating the adjacent design. In that case, the evidence supports the introduction of new elements. In other cases clues to the original design may be found on site or, in the case of terraces or buildings of the same period, features lost in one building may have remained next door. Historic documents like photographs, paintings or drawings can also be of great assistance. The reintroduction of missing details should be guided by the significance of the building. A deep understanding of the building, its construction and its decoration will clarify how and which features may be reinstated.

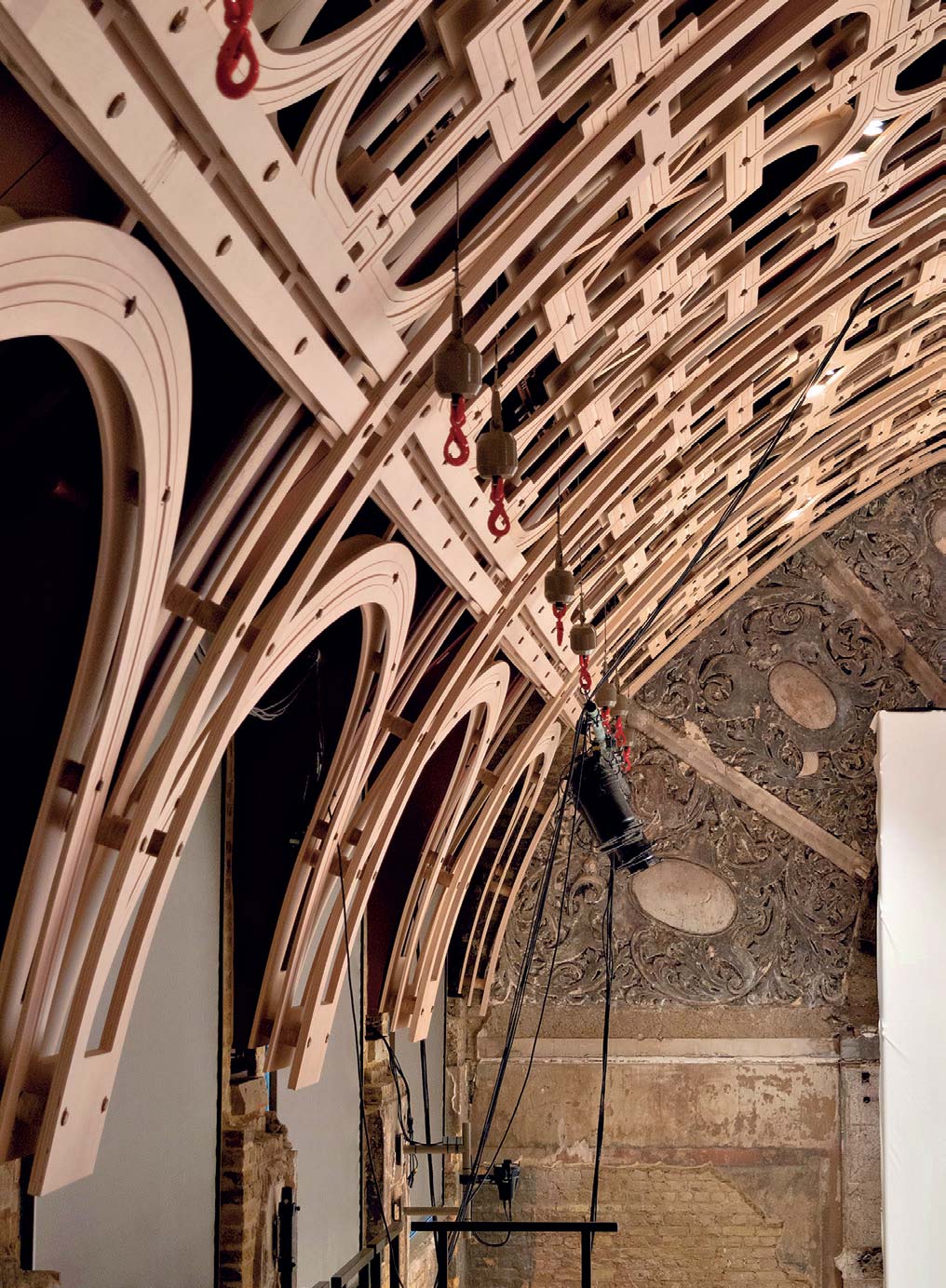

Authenticity is at stake when introducing new elements into a building: as well as the loss of original fabric there is the problem that new incorporations could be assumed to be original. So even in cases like the Glasgow School of Art where there is a good record and evidence of the original design, the repair is not straightforward. On the one hand a like-for-like reconstruction would recover the design value lost after the fire, on the other, a contemporary design within the original fabric would show the layers of its new life. A study of the building and its context would result in a better strategy for reintroducing features. Even when additions are intended to appear as new interventions, the research and analysis of the building’s significance can guide the new proposal.

The contrast between original and new features can emphasise the evolution of a building, but it can also distract from the main features if, for instance, the addition breaks the characteristic symmetry of a façade. It is a fair assumption that reintroducing new features in Grade I listed buildings should be discreet to avoid disrupting their ‘exceptional interest’. Given these buildings’ uniqueness, traditional materials, techniques and design tend to be more appropriate. In the case of Grade II*, and certainly even more with Grade II, the contrast between historic and new could add value. At Astley Castle, for instance, contemporary design was considered suitable to bring the Grade II* listed building back to life.

When carrying out repairs, the will to recover the original glory of the building might be tempting, but the significance of a building lies in more than just its aesthetics. Although often less immediately obvious than its architectural value, the existing fabric of a building holds historical and evidential value. The materials used and how they were put together over time also have value to be considered. As we ponder on the importance of those existing elements, the aspect of authenticity comes into play: can the value of the original fabric be replicated? Any attempt to reinstate a specific building period will reduce its richness. A modern intervention could mimic the old materials and construction systems, but it remains a new intervention.

However, as change is inevitable to guarantee the future of historic buildings, sustainability and reversibility should come into place. Repairs are necessary over time, and modern interventions might be required to repurpose vacant buildings. Addressing the sustainability of the materials and the maintenance resulting from the proposed addition will inform a good reinstatement. More easily achieved with vernacular buildings and traditional materials, it can be challenging with post- war buildings, given their experimental character. In those cases, a reversible solution could be the most sustainable option if well integrated within the existing fabric. Assessing alternative options and their consequences before implementation will reduce the risk of recurring repairs and damage to the existing fabric.

Determining the correct approach to the reinstatement of features is not simple, as it requires a detailed study for each case scenario. Historical research, on-site inspection and analysis of architectural evidence should be the starting point. Understanding the significance of the building will provide guidance and balance on the value of its different elements. The strategy proposed should consider any possible negative impact and a way to correct or balance it. The correct reinstatement of features – a solution that balances historical, aesthetic and evidential values – will preserve, or even enhance, the significance of the building while safeguarding it for future generations.