The Manufacture of Replica Inlaid Medieval Floor Tiles

Diana Hall

|

||

| Tiles at Winchester Cathedral after 700 years of wear |

Of all the decorative elements in a church interior, those attached to the floor are the most vulnerable. Constant erosion by visitors and worshippers, salts carried in rising damp, lack of maintenance and harsh proprietary cleaning agents all take their toll. Yet there is still an astonishing variety of original medieval flooring designs which has survived over the centuries in churches and cathedrals throughout the country.

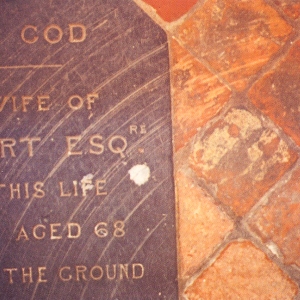

Often of enormous archaeological importance and decorative interest, designs include fine ledger stones which still bear elegant lettering and elaborate heraldic devices or even memento mori such as skulls, reminding the living of the fragility of life. Original memorial brasses are common, particularly in the South East of England. Paving includes cosmati designs in which the shape of the individual stone tiles form elaborate patterns; decorative designs using stones of different colours; and clay tiles.

The medieval inlaid tiles, which are considered here, may seem relatively mundane by comparison, if only because of the level of erosion which has taken place over the centuries since they were first made, which has left little more than ghosts of their original designs.

Inlaid tiles, or ‘encaustic’ tiles as they are also known, are fired clay tiles with a simple pattern such as an heraldic motif picked out in a clay inlay of a contrasting colour, usually in white on a red ground. The tiles are glazed and were originally fired in a wood burning kiln.

During the firing process, some vitrification occurs in the glaze, resulting in the hard, glasslike finish. Little vitrification occurs within the body of the clay. As a result, the glaze is substantially harder and more durable than the underlying body. It is this layer which contributes to the durability of the tile. However, in even the best fired pieces, the surface gradually wears over the centuries, until the softer material beneath is exposed and deterioration accelerates rapidly. The coloured inlay, which may be just a few millimetres in depth, wears away leaving just a plain clay body.

Inlaid clay tiles are common in churches and cathedrals throughout the United Kingdom. Particularly good examples can be found at Lichfield Cathedral, Winchester Cathedral, Cleeve Abbey and Byland Abbey, to name but a few. Some of these tile ‘pavements’ have deteriorated to such an extent that it has become necessary to consider drastic measures if they are not to be lost forever. In addition to consolidation and repair, options which need to be considered include:

|

|

| Tiles at Winchester Cathedral after 700 years wear |

- covering all original medieval tiles to preserve them as archaeological artefacts (albeit unseen)

- cordoning off tiled areas preventing their use but allowing them to be seen (an impractical solution in most instances)

- requiring all visitors to wear soft, protective overshoes which will prevent further abrasion

- removing the tiles to a safe place and replacing them with replicas

- ignoring the problem and leaving the tiles to deteriorate.

Replacement of the originals is ethically questionable, as the loss of the original medieval work will detract from the historic integrity and archaeological importance of the building, and the new work may confuse the history of the building, particularly if it is indistinguishable from the original. The introduction of new replicas is most appropriate where areas of original tiles have been lost altogether, particularly if no attempt is made to fake the appearance of an ageing tile. In some instances the replacement of originals with replicas may also be justified where originals have lost their pattern altogether.

Recreation of the original pattern provides a unique opportunity to present an interior in the manner originally intended, and the effect can be dramatic. At Winchester, areas of new work now form a vivid carpet of colour reflecting the light from the stained glass windows and the elegance of the early english architecture. However, replica tiles were introduced in limited areas only.

Winchester Cathedral has the largest area of 13th century inlaid tiles still in their original position in England. The tiles have became very worn from continual visitor traffic and daily cathedral life, and in many areas the original glaze has worn away entirely leaving very friable, soft cored, patternless tiles behind. A decision to conserve and restore the retrochoir pavement was taken by the Dean & Chapter of Winchester Cathedral on the advice of their architect, Peter Bird of Caroe and Partners. Cliveden Conservation Workshops were asked to conserve the existing tiles while Diana Hall was commissioned to replicate nine original designs to replace a number of 19th and 20th century plain tiles which had been laid during previous building and restoration works.

By understanding traditional techniques used in the past and the different types of clay employed it is possible to replicate the tiles with some degree of historic accuracy and to produce a floor of the same quality as the original.

Before starting work, documentary evidence was studied to establish the date when the tiles were made and the source of the clay originally used. Research by Christopher Norton which had been published in the paper ‘The Medieval Tile Pavements of Winchester Cathedral’ indicated that 17 different patterns dating from 1260-1280 had been used. Two distinct groups of tiles were affected, distinguished by their depth of inlay, their size and the appearance of either four or five ‘key holes’ in the back of each tile. One group of tiles are close in style and technique to those of the early Wessex industry, with four key holes in the back. The Court Rolls of Winchester College indicated that the second group, with five key holes, were made at nearby Otterbourne during the 14th century. The body fabric of both groups of tiles are very similar and are likely to have been made using clays from the Reading Beds.

|

|

||

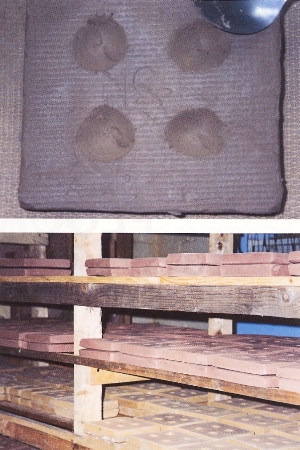

| Top: Prepared clay in the mould |

Top: Keyholes on the back of the tile | ||

| Bottom: Filling the impressed pattern with the fluid clay slip | Bottom: Drying tiles stacked face to face to minimise warping |

The first stage in the replication process involved careful research to determine the methods to be used. A selection of fragments of tiles from the floor were studied under a microscope to identify the body fabric type, colour and texture. It was noted that the clay was fine, orangey-red with small areas of paler clay with small inclusions, suggesting that little mixing had been carried out. Local clay from Reading Beds was chosen to match the samples examined. The white inlay was studied and a mixture of white earthenware clays were mixed together to obtain the correct shrinkage and compatibility with the red body clay when fired. Various glaze recipes were tried for colour and fit; galena (the mineral form of lead sulphide) suspended in beer lees produced the best match, resulting in the lovely chestnut glow that the original tiles displayed. The designs were traced from the surviving tiles in the pavement then adjusted to take account of wear, but not over corrected, ensuring that the original uneven character of the originals was retained. Slightly over-sized wooden moulds were made which allowed for the shrinkage of the clay, and stamps were carved in beech to match the motifs chosen – again slightly over-sized – to fit the moulds.

Once research and experimentation was concluded, the first set of tiles were produced to replace some 20th century tiles that had been inserted during the installation of services to the Lady Chapel. A second set was then made for the north side of the retrochoir to complete an area of pavement where a table tomb had stood. The tomb, which was of Sir Arnauld de Gaverston, a knight who died 1302, had been moved to allow greater public access to the east end of the cathedral.

Initially the raw clay had to be cleaned of stones and larger organic matter. It was then soaked and ‘pugged’ before being weighed, wedged into a square shape and placed into the mould to form the tile. The tile was then stamped to reproduce the pattern in relief, leaving an impression in the surface of the soft clay. Keyholes were also cut into the back at this stage to help drying and to help the tile to key to the mortar when finally installed. The impressed pattern was then filled with a white ‘slip’, a fluid clay mix, and left to dry. When leather hard, the excess slip was cut back, revealing the clear definitions of the pattern. Then the tiles were left to dry completely for three to four weeks. Due to various delays, this took place during the coldest, dampest months of the year, although it is well known that medieval man only made bricks and tiles during the spring and summer!

|

|

||

| Damage from salts due to moisture trapped beneath a carpet at St Mary’s, Apuldram, Chichester | Scratches to the floor caused by grit trapped beneath the main entrance door at St Cross, Winchester |

After drying, the glaze was brushed on to the surface of the tiles and fired. Traditionally a wood fired kiln would have been used. However, it was decided that it was impractical to build and fire a wood fired kiln due to the unpredictable results that would be achieved during the winter months. A gas fired kiln had proved a good alternative as it allowed a more controllable firing cycle. It also gave sufficient variation in the degree of oxidation and reduction to produce an adequate range of colour tone in the glaze, varying according to the location of the tile in the kiln.

The tiles were then laid in a lime mortar bed following the original layout of the pavement. Although there is a great contrast between the replica tiles and the surviving medieval tiles, the new work gives a clear insight into the full beauty of the floor as it must have appeared in the 13th century.

The care and maintenance of these wonderful floors must be paramount. Good management measures can be introduced to reduce damage to the flooring, cheaply and easily, and are of the utmost importance. These include the removal of grit from paths in the immediate vicinity to the main entrance and keeping them regularly swept, the use of door mats and the introduction of polite notices requesting visitors to wipe their feet. Carpets should not be used over important floors, as these too trap grit and damp, while the overzealous use of the vacuum cleaner consumes soft lime mortar and fractured pieces of worn tile. these must be monitored and protected.

The use of soft, disposable shoe covers could be introduced in all historical buildings, and more research is required into the use of microcrystalline wax polishes as a protective coating for the surface of the tile.

To care for our clay tile pavements there must be a good understanding of how they were made, the properties of the clays that they were made of and a knowledge of the traditional techniques that were used. Where conservation of the existing material is not possible, the option of replacement with replicas provides a valuable alternative. We are now able to create wonderful 20th century floors with new designs displaying the craftsmanship of today and showing our influence in the continuous evolution of these majestic buildings.

~~~

Recommended Reading

- ES Eames, Catalogue of Medieval Lead-glazed Tiles in the Department of Medieval and Later Antiquities, British Museum Publications, London, 1980

- ES Eames, English Tilers Medieval Craftsmen, British Museum Publications, London, 1992

- C Norton, The Medieval Paving Tiles of Winchester College, Proceedings of the Hampshire Field Club, Vol 31, 1974

- C Norton, The Medieval Pavements of Winchester Cathedral, Medieval Art and Architecture at Winchester Cathedral, BAA Conference Transactions, 1980