George Whitefield at Kingswood

Edward Green

|

|

| The Kingswood Tabernacle in 2007 viewed from Park Road |

From the street, it is difficult to believe that the large near-derelict edifice in Park Road, Kingswood on the outskirts of Bristol, is Grade I listed, or that it bears testimony to one of the most important figures in the history of nonconformity in England. Yet, the Tabernacle building does just that. Dating from 1741, it was commissioned by the great 18th-century evangelist George Whitefield, who had first visited the area just two years earlier. Now in a poor state of repair and almost completely open to the elements, the Tabernacle gained some recent notoriety when it featured in the first series of BBC television’s ‘Restoration’.

The area witnessed the advent of the Methodist movement, with both Whitefield and his friend (and later rival) John Wesley preaching here. Kingswood was a district of approximately 20 square miles. Although it lay within the borders of four parishes, it had no parish church, no school and only one nonconformist place of worship: a small Baptist church at Hanham, which had been built in 1714. Close to the commercially prosperous port of Bristol, the area was largely populated by coalminers, living and working in atrocious conditions. Men, women and children laboured long hours in the mines, this being just over a hundred years before Lord Shaftesbury’s moves to ban women and children from undertaking such work.

THE RISE OF WHITEFIELD

George Whitefield was born in 1714 in Gloucester, 35 miles to the north of Bristol, where his father was the owner of the Bell Inn. There was a history of preachers in the family, including George’s great uncle, Rev’d Samuel Whitefield, who was Rector of Rockhampton near Thornbury, Gloucestershire. Whitefield’s father died when George was two years old and for some years his mother ran the business alone. A subsequent marriage proved disastrous for the family business and George, aged 15, had to abandon his education to assist his family.

|

||

| George Whitefield by John Greenwood, published by Robert Sayer, after Nathaniel Hone mezzotint, (c1768) © National Portrait Gallery, London |

Despite this, Whitefield did manage to get to Oxford at the young age of 17, but as a servitor. As such he had to act almost as a butler to a small group of students while carrying out his studies. It was here that Whitefield met John and Charles Wesley as the men prepared to become Anglican priests. They had formed a university club called Holy Club, whose members met for biblical study and discussion as well as prayer. Following ordination in 1736, Whitefield travelled to Georgia where John Wesley was already carrying out missionary work, initially aimed at the Native Americans. Georgia was then a young colony which had been founded only a handful of years before.

These young men developed the art of open-air preaching, following the example of Welshman Howell Harris. In areas such as Kingswood there was no church building available to a potential congregation and even if there had been, a church would not have been large enough to accommodate them. More than this, however, the appeal of preaching to an audience in the open air was one of addressing the people on their own territory: people who may well have initially felt alienated from the established church. Whitefield’s enthusiasm for open air preaching is clear from his journals: 'Blessed be God that the ice is now broke, and I have now taken the field'. Echoing Hosea 4:6, he added 'pulpits are denied, and the poor colliers ready to perish for lack of knowledge'.

Whitefield first visited Kingswood in the spring of 1739. On Wednesday 21 February he preached to 2,000 in the open air, two days later to between 4,000 and 5,000, then on the Sunday an estimated 10,000 people came to hear him preach. As another journal entry of the time reveals:

At four I hastened to Kingswood. At a moderate computation there were about ten thousand people… All was hush when I began: the sun shone bright, and God enabled me to preach for an hour with great power, and so loudly that all, I was told, could hear me.

His popularity soon spread from the Bristol area to other parts of Gloucestershire and into Worcestershire and Wales. On Monday 2 May 1739, John Wesley followed his example and preached for the first time in the open air in England. On the evening of the previous day, Whitefield had previewed Wesley’s appearance, announcing that he was ‘unworthy to unloose’ Wesley’s shoes.

Whitefield preached in Bristol and Kingswood for seven weeks. He then left this work in the hands of John Wesley, while he undertook preaching engagements in Wales, the Midlands and London before sailing to Georgia. Before his departure the local coal miners had collected £20 towards a school for their children and they promised a further £40. This sum enabled Whitefield to commence building in the town.

|

|

|

|

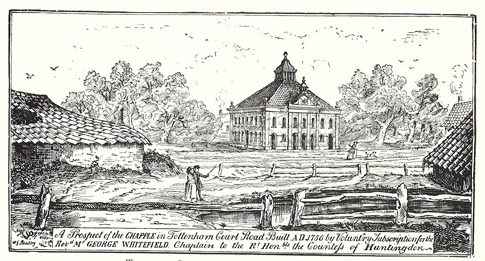

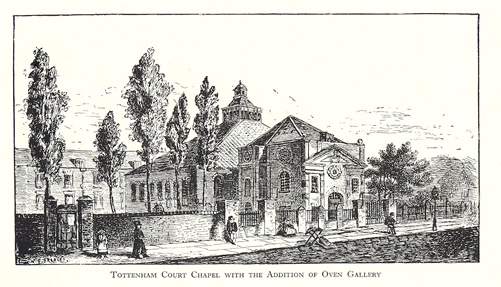

| Two engravings of Whitefield's tabernacle in Tottenham Court Road, London, destroyed in World War II |

THE SCHISM

The Kingswood school was the first building constructed for Whitefield in the town. A young man called John Cennick was appointed as the school’s first teacher by John Wesley. Cennick’s family background was Quaker and he worked with both Whitefield and Wesley, but he fell out with the latter and eventually joined the Moravian faith, constructing the first Moravian Church in Kingswood. His, and also Whitefield’s theological differences with the Wesleys eventually led to the confiscation of the original school building by John Wesley, and a second Kingswood school was subsequently built by Whitefield and Cennick.

Whitefield, Cennick and the Wesleys’ disagreement was over the fundamental theological ideas of Calvinism versus Arminianism. The Wesleys favoured Arminianism which was also the position of the established church. Whitefield and Cennick were disposed towards Calvinism. Nevertheless, Whitefield and the Wesleys still had respect for each other: indeed, John Wesley preached a sermon in Whitefield’s Tottenham Court Road Tabernacle, following Whitefield’s death.

In March 1741 Whitefield returned from America and by June of that year had decided to build a meeting room in Kingswood, writing to Cennick and enclosing an initial £20. Work commenced almost immediately, and Cennick laid the foundation stone on 18 June. This building, which opened early the following year, was the first phase of the tabernacle, and forms the central section of the now threatened tabernacle building. It was tripled in size in 1802, and was extended again in 1830.

George Whitefield died on 30th September 1770 while on his seventh visit to America. He had been preaching in towns in New England for two months before his death and gave his last sermon on the day he died from an open window at the house of a friend at Newbury Port. He is buried beneath the pulpit of the Old South Presbyterian Church in Newbury Port, Massachusetts.

THE REMAINING ARCHITECTURAL LEGACY

Whitefield’s churches were known as tabernacles because of their intended temporary nature. This alludes to both the tabernacle of the Israelites in the wilderness (Exodus, 25:25) and the fact that Whitefield was careful not to be seen forming a church which was in competition with the Church of England. This was at a time when the Methodist movement was still within the Church of England. (It did not separate until four years after John Wesley’s death.)

Other tabernacles set up by Whitefield included a tabernacle at Penn Street in Bristol founded in 1753 and tabernacles at Dursley and Rodborough, also in Gloucestershire. Some financial assistance came from the Countess of Huntingdon, a rival nonconformist to Wesley. She had appointed Whitefield as a chaplain. Whitefield’s converts usually joined existing nonconformist churches – in England the Congregationalists, in Scotland the Presbyterians.

The first of Whitefield’s tabernacles in the capital dated from the early 1740s. Situated at Moorfields, the original wooden structure was replaced by a more permanent building in 1752. The impressive building had a characteristic lantern roof and could seat up to 4,000 people. All but one of Whitefield’s tabernacles eventually became part of the Congregational Church (formerly the Independent Church).

Another Whitefield tabernacle in London, again dating from the 1750s was situated in Tottenham Court Road. Its foundation stone was laid on 10 May 1756 and Whitefield himself preached at the Tabernacle’s opening in November of the following year.

It was the Tottenham Court Road

tabernacle which was to gain the poignant

notoriety of being hit by a German V2 rocket

during the Second World War. The building

was destroyed on Palm Sunday 1945, by what

was reputedly the last V2 to strike London. Its

site is now occupied by a smaller replacement

chapel opened in 1957, 201 years after the

foundation of the original building. Now the

American Church in London, the building

(at the corner of Goodge Street) is called

the George Whitefield Memorial Church. It

has been described as the most significant

memorial to Whitefield anywhere in the world.

|

|

| The mid-19th century Masters (Congregational) Church at Kingswood |

THE KINGSWOOD TABERNACLE SAGA

After Whitefield’s death, nonconformists

continued to worship in the vicinity of his

Tabernacle building for over 200 years, and the

tabernacle was listed as far back as 1951. Today,

however, the site presents a sorry spectacle

of ruins, derelict buildings, and overgrown

open spaces. There is nothing to indicate its

importance to English religious history. Gone is

the bronze plaque from the side of the building

which once proudly announced: ‘This building

was erected by George Whitefield BA and

John Cennick, AD 1741. It was Whitefield’s

first Tabernacle, the oldest existing memorial

to his great share in the 18th century revival.’

The Whitefield Building Preservation Trust was founded over 10 years ago with the aim of restoring and finding viable uses for this small complex comprising of the remains of the Tabernacle itself, the Masters Church, the Chapel House and a graveyard.

Since the original school building (taken by Wesley) was demolished in 1919 and Cennick’s Moravian Church building, which dated from the 1750s, has gone too, this makes the Tabernacle the last remaining Kingswood building connected with the 18th-century religious revival. Its Grade I listing reflects its historical significance.

The picturesque mid-19th-century church building on the same site was designed by Henry Masters and served nonconformists in Kingswood until dwindling congregations forced its closure a quarter of a century ago. Its attractive spire and west window tracery are in marked contrast to the somewhat austere Whitefield Tabernacle building, now on English Heritage’s Buildings at Risk register.

The recent history of the site has not been without controversy. The United Reformed Church recently sold the sizable plot to a developer and plans were submitted in late 2006 to restore the Tabernacle and convert it into a restaurant. Part of the application includes the conversion of the Masters Church and Chapel House into 19 and six apartments respectively, for which a service road and car parking is proposed through the disused burial ground.

Standing as the most lasting memorial to a man who has been described as ‘the most controversial preacher of the 18th century, and perhaps the greatest extemporaneous orator in the history of the English church’, the Kingswood Tabernacle still awaits an uncertain future. Its conservation raises questions about suitable uses for redundant churches, as well as tight restrictions regulating changes of use to Grade I listed buildings. It is hoped that the structure will not be left to decay for another quarter of a century.

~~~

Recommended Reading

- Belden, Albert D, George Whitfield –

The Awakener – A Modern Study of the

Evangelical Revival, London: Sampson, Low, Marston & Co

- Dallimore, Arnold, George Whitefield: the Life

and Times of the Great Evangelist of the

18th-century Revival, London: Wakeman

Trust, 1990

- Dictionary of National Biography

- Downey, James, The 18th Century Pulpit,

Oxford: Clarendon press, 1969

- Eayrs, George, Wesley and Kingswood and its

Free Churches, J W Arrowsmith: Bristol, 1911

- Gillies, John, Memoirs of G Whitefield,

Middletown, 1838

- Gledstone, James Paterson, The Life and Travels of George Whitefield, London: Longmans, Green and Co, 1871