Graffiti in Context

from cultural phenomenon to heritage crime

Catherine Woolfitt

The nature of the problem. The historic building façades forming the background to this urban skate park have been covered as graffitists reach progressively higher to make their marks. The building to left of frame is a Grade II listed swimming pool. (All photos: Catherine Woolfitt)

The prevalence of graffiti reflects the turbulence of the current social and political climate. Monuments associated with controversial historic figures and events (‘contested heritage’) have been increasingly targeted in recent years.

Prominent examples include repeated graffiti attacks on the statue of Winston Churchill in Parliament Square, London, and the graffitied sculpture of the slave trader Edward Colston, which was toppled by protesters in 2020 and is now displayed in a museum.

Historically, graffiti has been an outlet for political or social protest, to express views at variance with the status quo, including, for example, the highly evocative words and images conscientious objectors inscribed on their cell walls at Richmond Castle and elsewhere during the first world war.

In many cases, however, graffiti bears no relationship to the building or site where it is applied. Perpetrators typically target building surfaces indiscriminately, regardless of whether they are modern or historic, apparently selecting surfaces that present a blank canvas, high visibility, and, in some cases, a physical challenge.

Although graffiti is most pervasive in urban areas, it extends to sites in remote or rural settings where illicit, anti-social behaviour may be the motivating factor, or, more rarely, where specific groups or individuals target a monument for its symbolic or religious significance.

The term graffiti derives from the Greek word γράφειν (graphein) meaning to write. Fundamentally, graffiti in whatever form, pictures, symbols, text, whether inscribed (cut) into surfaces, or applied with paint or other media, is a form of communication.

Understanding the motivation of the graffitist and the message being conveyed may inform preventive measures, which range from physical barriers that might be deployed against recurrent attacks, to broader social and educational engagement aimed at preventing further incidents.

Street Art Versus Graffiti

The Greta Thunberg mural on the Tobacco Factory in Bristol, painted in 2019 by Jody Thomas, is an example of street art designed for a specific site and executed with

the building owner’s consent.

In some urban areas, for example Stokes Croft, Bristol, and Camden, London, street art forms an integral part of the alternative, unconventional character of the streetscape and the ‘sense of place’.

The street art movement is often cited as a contributing factor to the proliferation of graffiti. It is true that spray paint, so commonly used by street artists, has become the most popular graffiti medium, being readily available, portable, and very convenient to apply.

Those identifying as street artists might aspire to the status of their more famous counterparts, like Banksy or Jean-Michel Basquiat, whose work has won public recognition and has featured in international art exhibitions. However, public perception of what passes for street art versus unwanted graffiti varies widely.

The boundary between street art and graffiti may sometimes seem difficult to define, but in legal terms any work carried out on a building without the property owner’s consent is illegal.

In general, art works (murals) designed for a specific location and applied with the owner’s consent can be readily distinguished from graffiti that has been applied without consent as an act of vandalism. The latter, unwanted graffiti, is widely perceived, and classified in law, as a manifestation of anti-social behaviour and a form of criminal damage.

It has been widely observed that once graffiti appears it tends to proliferate, like litter. Consequently, graffiti removal is often attempted in haste, to prevent further attacks. Unfortunately, attempting removal without sufficient understanding and resources can further disfigure vulnerable historic building surfaces.

Graffiti of Historic Significance

In parallel with the increase in unwanted and randomly applied graffiti, awareness of historic graffiti has grown in recent years, and the significance of previously overlooked or misinterpreted marks increasingly recognised.

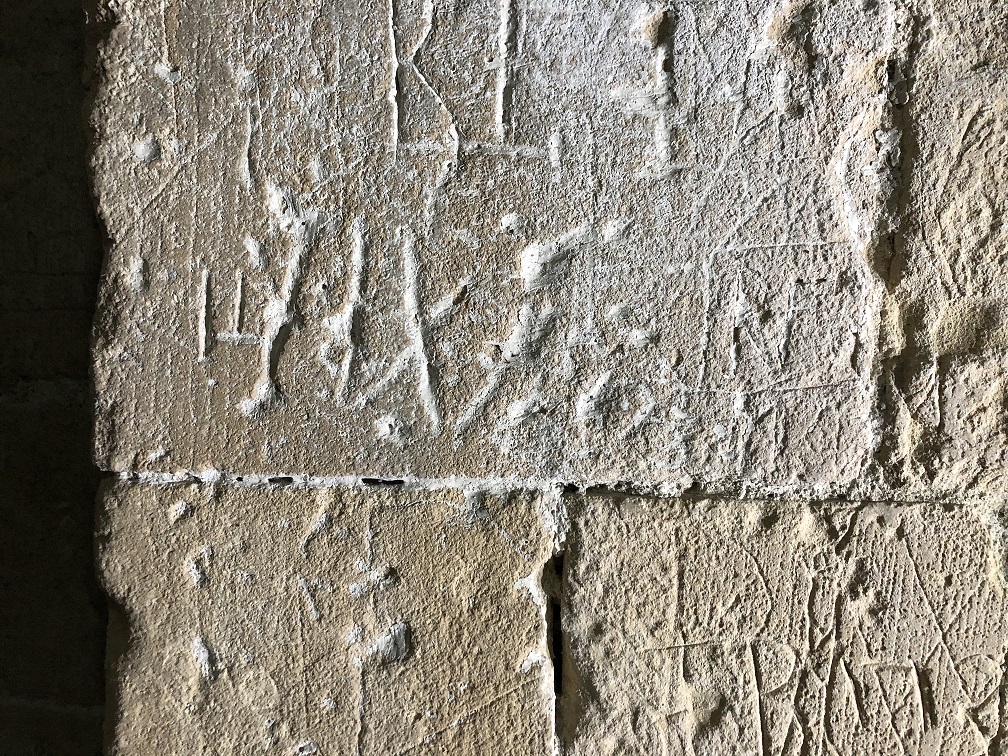

Among graffiti of historic interest are characteristic marks etched into masonry and other building surfaces, and on rock faces in caves and quarries, which have often been previously misinterpreted as evidence for tool sharpening or vandalism and are now understood to be marks invoking protection against evil or misfortune.

These are referred to as ritual protection marks, and sometimes described as ‘witch marks’ or apotropaic marks. These include black burn or scorch marks on timber. Diagonal lines, boxes, mazes, and mesh marks, thought to represent ‘spirit traps’, were often inscribed at openings, near windows, doors and fireplaces.

Recent study and media reports have cast light on the extent and significance of these marks at sites such as the caves at Creswell Crags, near Sheffield. Two very common types of protective mark are the daisy wheel (or hexafoil), inscribed with a compass, and the double V (VV mark), which sometimes appears in inverted form, resembling a splayed, inverted M.

The double V is understood to be an invocation of the Virgin Mary, often referred to as a Marian mark. Some scholars point out that very similar geometric marks or symbols appeared much earlier, pre-Christianity, in prehistoric cave art across Europe.

Ritual protection marks are common in caves, such as those at Creswell Crags, in mines, and on historic buildings of all types, ecclesiastical, domestic, vernacular and military, up to the 19th century. They provide a window on the views of people who are under-represented in the historical record, whose beliefs and thoughts appear infrequently in written documents and other material evidence.

Recent reports of previously hidden or undetected historic graffiti of various types have highlighted the potential for illuminating discoveries.

Prominent among these is the discovery of a concealed and blocked passageway at the Houses of Parliament in Westminster where graffiti pencilled on the walls by the 19th century builders included the following:

"These masons were employed refacing these groines… [ie repairing the cloister] August 11th 1851 Real Democrats." (Real Democrats were part of the suffrage Chartist movement, which called for reforms to allow every man from the age of 21 to have a vote, and for would-be MPs to stand even if they had no property.)

Repair work and alterations that normally accompany the redevelopment of historic buildings are likely to expose historic graffiti on previously concealed or inaccessible surfaces. It is important that such evidence of the past is not overlooked, potentially lost, or destroyed.

Unfortunately, historic building owners more typically face the challenge of removing unwanted graffiti than the exciting discovery of new graffiti of historic interest.

Responding to a graffiti incident and the risks of hasty cleaning attempts

|

|

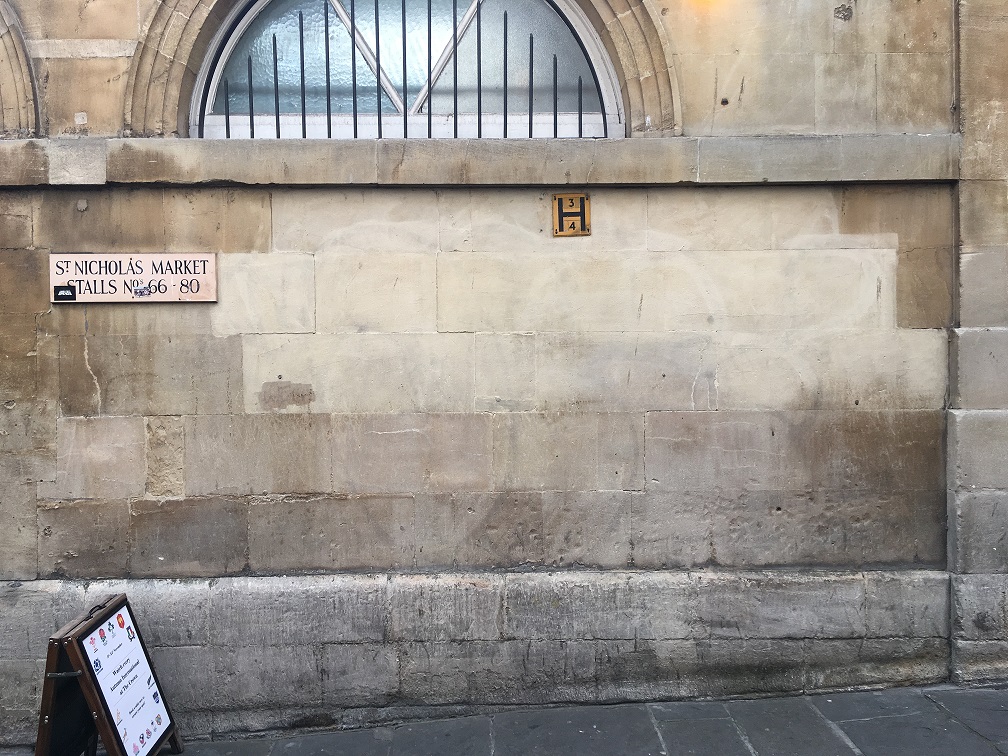

| Scratching and other marks left by an attempt to remove graffiti from Bath stone, a relatively soft and porous material |

Due to the tendency for graffiti to proliferate, there is often a push to remove freshly applied graffiti as rapidly as possible, to discourage further incidents and demonstrate that repeated attacks will not be tolerated.

This is understandable but a balance needs to be struck between rapid removal and taking the time to procure effective cleaning services from an informed and suitably skilled contractor.

Unfortunately, hasty removal attempts carried out without assessment and understanding of the graffiti type (medium), the surface (substrate) type and condition often result in further surface disfiguration.

Readily available cleaning methods, such as mechanical cleaning (using pressurised water or abrasive) and scrubbing with metal bristle brushes, are designed for robust modern materials such as concrete, and are too aggressive for historic building surfaces.

The damage caused by routine removal of graffiti using such methods is readily visible in places where repeated removal has been carried out on historic facades.

The scratches, scouring and other marks left by such removal attempts are permanent. Incomplete removal often mobilises coloured components of the graffiti medium, fine pigment and other particles, causing these to ‘bleed’ and spread, penetrating into small surface pores and often becoming more difficult or impossible to remove completely.

Soft, porous, and open textured surfaces/materials, for example Bath stone and handmade bricks are particularly vulnerable to damage. Assessment and understanding of the surface type and condition is essential to prevent unnecessary damage and ensure effective graffiti removal.

In some cases, it may be advisable to conceal graffiti with temporary barriers or covers, rather than attempt removal without the necessary resources and skills in place. This may be the preferred solution for graffiti that features offensive text or symbols, or that constitutes a hate crime, motivated by hostility or prejudice based on race, religion, sexual orientation, or disability.

Offensive graffiti may be covered in several ways, subject to site and logistical constraints. Free standing monuments can be concealed using wraps (opaque sheeting) secured in place with adjustable ties or straps.

Opaque sheeting may be draped over vertical surfaces and secured with timber battens, provided fixings for these are sensitively located, typically in mortar joints to minimise the impact on historic fabric. On free standing walls it may be possible to drape protective sheeting over the face, with weights integrated, as in the hem of a curtain, to secure the cover in position.

In exceptional cases, the option of applying a temporary coating over graffiti, using a material such as limewash or sheltercoat, may be appropriate, subject to consideration of the need to subsequently remove this coating as well as the underlying graffiti.

An important first step in response to any graffiti incident is to obtain photographs that capture the graffiti both in the site context and in detail. The photographic record should include general views, to illustrate the scale of the graffiti and details of the graffiti medium (or media if more than one type of material has been applied).

A photographic record is essential for every subsequent step – procuring cleaning advice and removal services, making an insurance claim for the damage, and taking legal action.

It is important to check the legal status of the building and confirm the need for consent prior to carrying out any cleaning or other remedial work. Again, photographs are helpful in this context, to illustrate proposals for cleaning and any other work, for submission to statutory authorities.

Graffiti media and vulnerable historic surfaces

Safe and effective removal starts with an understanding of the building surface (substrate) and the medium used for the graffiti. Spray paint is by far the most common medium, but marker pens and ink pens are also used, as well as other portable materials such as nail varnish and lipstick.

The binders, solvents, dyes, pigments commonly employed in these and other media vary significantly, and a cleaning method suitable for one medium may be unsuitable for another. Understanding the composition of the graffiti medium is key to assessing how the graffiti marks respond to proposed cleaning methods.

Graffiti inscribed or scratched into a surface cannot be removed without further damaging the surface. However, depending on the surface material, it may be possible (if a suitably skilled contractor is engaged) to fill the incisions or scratches, to make the graffiti illegible or at least reduce its legibility.

The surface type and its physical characteristics determine how it will respond to cleaning (graffiti removal). Soft, porous limestones, hand-made bricks, and lime-based plasters and coatings can all be classed as vulnerable to damage using aggressive cleaning methods.

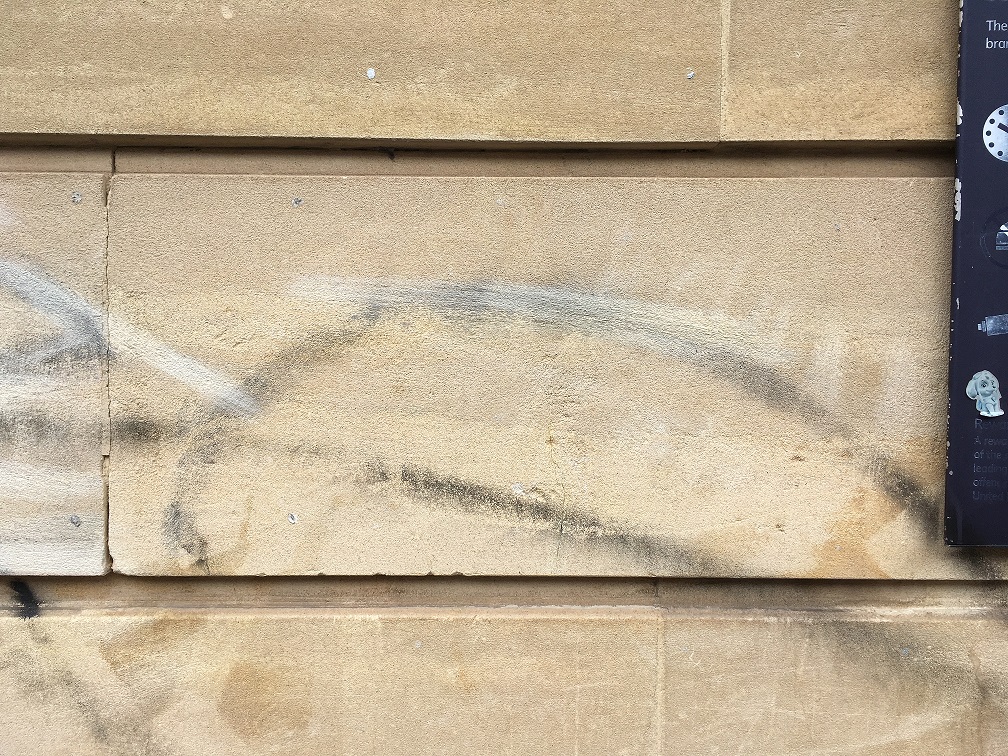

In general, it is not possible to remove graffiti effectively from such surfaces using nonspecialist (generic) cleaning methods, and residual staining (and ‘ghosting’) is likely to remain after cleaning.

Conversely, hard, dense, non-absorbent/non-porous masonry surfaces, such as polished granite, glazed brick and terracotta, glass, and smooth textured concrete are relatively impermeable, nonporous and resistant to penetration of graffiti media.

Such surfaces are therefore typically easier to clean. However, these surfaces can be damaged by etching using strong chemical cleaning agents or abraded by mechanical cleaning using excessively high pressures.

Effective graffiti removal

Spray painted graffiti on glazed terracotta: the paint runs illustrate the relatively impermeable (smooth and

non-porous) nature of the glazed surface Above: before graffiti removal Below: after graffiti removal

|

|

There is considerable variability in the type of graffiti medium employed, and in the type of surface (material) that may be targeted, as well as the surface condition.

Consequently, the cleaning (removal) method must be tailored to fit – a generic ‘one size fits all’ approach is very unlikely to be effective.

In most urban areas local planning authorities (LPAs – councils) offer a removal service, which can be accessed online. However, this typically comes with a caveat and a damage waiver, absolving the LPA and their cleaning subcontractor of responsibility for damage, including any surface damage that may occur during cleaning.

In this context, cleaning services are offered as part of environmental services and street cleaning, often falling into the same general category as removal of chewing gum, flyposting, dog fouling and dead animals!

In general, cleaning services offered in this way cater for relatively robust (hard/resistant) surfaces, such as pavement and concrete, and consequently often employ high pressure methods (normally water, sometimes pressurised air and abrasive).

This kind of standard approach (designed/intended for modern buildings and street materials and finishes) is likely to be damaging to historic building surfaces. Selection of cleaning method should always be subject to a small-scale removal trial in a pre-agreed area.

A trial is essential to determine the optimal cleaning method, which might include several stages or processes and might potentially include more than one cleaning agent (proprietary product). The trial area should be inspected after the surface has dried and the cleaned section should be free of residual staining and marks.

A suitably skilled and experienced contractor should be able to demonstrate their understanding and skills by providing examples of graffiti removal work from historic building surfaces, including ‘before and after’ photographs to illustrate these.

There are many proprietary cleaning products (chemical cleaners) designed to target specific graffiti media and binder types, some of which are designed specifically for historic buildings.

This latter group of specialist cleaning products and systems is preferable, and includes chemical cleaners designed to be easier to apply and less hazardous for the user, the surface, and the wider environment.

Among these are clear gel poultices which are easier to apply and control than liquid cleaners and can be left in place for the optimal duration (dwell time), provided they are not allowed to dry out.

In general, all chemical cleaning residues need to be rinsed from surfaces and this is most effectively achieved using a hot water pressure washer, subject to a site trial to ensure the minimal pressure setting is used to achieve effective cleaning without surface damage.

Further information on suitable cleaning methods can be found in the Historic England guidance document Graffiti on Historic Buildings: Removal and Prevention (Historic England 2021, co-authored with Jamie Fairchild) under the headings Mechanical, Water and Chemical cleaning.

This document includes case studies and covers graffiti prevention, from physical barriers such as anti-graffiti coatings on masonry to social measures, education, building local engagement and appreciation of the historic environment.

Recommended Reading

Graffiti Removal

Graffiti on Historic Buildings: Removal and Prevention, Historic England, Swindon 2021

Technical Advice Note (TAN) 18, The Treatment of Graffiti on Historic Surfaces, Historic Scotland, Edinburgh, 1999

M J Whitford, Getting Rid of Graffiti: A practical guide to graffiti removal and anti-graffiti protection, Routledge, London, 2016

Historic Graffiti and Protective (Witches) Marks

Matthew Champion, Medieval Graffiti: The Lost Voices of England’s Churches, Ebury Press, 2015

Professor Ronald Hutton, Physical Evidence for Ritual Acts, Sorcery and Witchcraft in Christian Britain, Palgrave Macmillan, London 2016

Brian Hoggard, 2021, Magical House Protection: The Archaeology of Counter-Witchcraft, Berghahn Books, 2021

Found Folk Art on Instagram:@foundfolkart