Guiding Lights

New approaches to the lighting of cathedral exteriors

Bruce Kirk

The new colour-changing lighting scheme at Lincoln (Photo: Lincoln Cathedral Chapter)

A nation's stock of religious buildings will normally include some of the greatest landmarks in the country. This is especially true for the United Kingdom as its churches, cathedrals and other places of worship include not only some of the very finest buildings in the land, but also some of the oldest and most prominent.

Lincoln Cathedral, founded almost a thousand years ago, held the title of the tallest building ever constructed, from 1311 until the late 1800s. It remained the tallest building in the UK for another hund red years until Canary Wharf tower was completed in 1988. For centuries the cathedral was considered to be one of the most visible buildings in the country, being seen across the vast swathes of relatively flat Lincolnshire landscape and sitting at the highest point of the appropriately named street ‘Steep Hill’.

There are several reasons why we choose to light to light buildings like this. Aside from showcasing these architectural wonders simply as landmarks, we should also recognise their importance to the people who see them as places of safety and refuge in a busy and stressful world. From a theological perspective, the fact that a spire points heavenward serves as a constant reminder to humanity of that which is beyond this world, of God, who transcends both time and space. Therefore the very act of lighting a cathedral becomes an act of evangelisation, reminding the communities in which these buildings are located that we are all on a journey from one life to another.

From personal experience gained working at St Paul’s Cathedral on 7th July 2005, the date of the London bombings, places of worship are widely seen as places of safety. On that day many people, in a state of shock, instinctively sought out and migrated to London’s churches and cathedrals for stability and certainty, whether to pray or simply to feel a much needed sense of comfort and security.

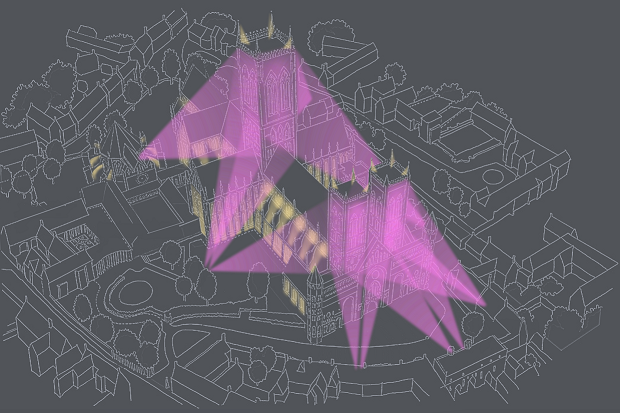

Graphic showing the various locations and coverage of groups of fittings at Lincoln Cathedral (Image: Light Perceptions)

When the new lighting for Lincoln was being considered, a very strong message was conveyed that the local population saw the cathedral as a guardian looking down and protecting the people of the city at night. A request was made to keep some of the lighting on throughout the night so that night workers and early risers would always feel a sense of security in the hours of darkness. Technology available today means that we can create the most subtle illuminations, or the most extravagant light shows using the same equipment by using a carefully configured control system.

At Lincoln, the previous floodlighting system had been commissioned in the 1970s for the Queen’s Silver Jubilee. Using the technology available at the time it required 50kW of sodium floodlighting which provided a solid orange glow across the higher levels of the building and also up into the night sky. The new system, completed in 2020, added subtle levels of gentle uplighting to the lower elevations of the building, additional floodlighting to the clerestories and further highlighting of the three great towers, in a soft, warm-white colour. The three towers can now be transformed with colours selected from an infinite palette when required. Since its installation the system has been used to celebrate New Year’s Eve with spectacular animated sequences and to enhance our national occasions, celebrating the Platinum Jubilee in red, white and blue. It has also been used to support clapping for carers, charity events, and even the local football team. The many different lighting configurations have been proudly publicised by local and national press as well as on social media. More recently, like many other public buildings, the cathedral has been lit with the colours of the Ukrainian flag.

(Photo: Lincoln Cathedral Chapter)

Two important questions arise here: firstly, who makes the decision on whether a special light show is merited? Care has been taken to establish a management plan for illumination options. There is clearly a delicate balance to be achieved between what are necessary and appropriate light shows, and those requests which are less significant and more often declined. The second question is one of energy costs and sustainability – how do we balance this desire for decoration and celebration with today’s drive towards net zero carbon? Surely this makes such illumination an expensive and unsustainable folly.

Lincoln’s scheme of the 1970s was indeed an energy hungry system with no allowance for dimming, attenuation or scene setting. However, the replacement one is carefully programmed to provide the right amount of light and only when required. Typically, it runs at 10 to 20 per cent of the previous loadings for a ‘full illumination’. In addition, the uplighting of the lower elevations has eliminated a number of dark and less attractive areas around the cathedral, boosting footfall and visual comfort around the area at night. Not only are the energy savings significant in themselves, with the more modern optics available in light fittings today, it is possible to dramatically reduce the amount of light pollution which previously resulted in an orange glow above the city.

Some 80 miles south of Lincoln, Ely Cathedral has also recently had a new external lighting scheme commissioned. The need for new lighting arose in part from the need to install a new walkway around the famous Octagon so that the popular rooftop tours could continue in a safer manner. The positioning of the walkway made the old floodlight positions unviable, so a new scheme was commissioned.

Whereas Lincoln Cathedral sits some 60 metres above sea level, Ely Cathedral, affectionately known as the ‘The Ship of the Fens’ due to its prominent position above the surrounding flat Cambridgeshire landscape, sits on a far lower mound of only 20 metres above the surrounding area.

The Octagon, long seen as the landmark symbol of the cathedral, is the only part of the exterior that has been floodlit. Nonetheless it has, for some years, been used for coloured light shows by adding sheets of theatrical lighting ‘gel’ to the front of the normally white floodlights.

As the Cathedral needed a new system, the Chapter (the governing body of the Cathedral) supported by the Friends of Ely Cathedral invested in a system that would offer a conventional white floodlighting as the norm, with the option of additional colour changing when required.

When Cathedral representatives were taken three miles south of the city to view a mock-up of two faces of the Octagon from the lighting test, the decision to proceed with a coloured scheme was swiftly made and detailed designs begun. Installed in November 2021 and well used over the Christmas and New Year periods, the flexibility of the scheme design took a fresh turn when, like many other public buildings, the request was made to reproduce the Ukrainian flag. This was a relatively easy programming task, the result of which has been widely welcomed.

Close-up of the Octagon at Ely with its new lighting scheme (Photo: James Billings)

The canvas for the illumination of Ely comprises the eight faces of the Octagon, each lit by two fittings which separately light the upper and lower parts of the elevation. The fittings are positioned on the roof surfaces of the Octagon. Conveniently, they are located perpendicular to the centre of each elevation, meaning that the upper and lower half of each face can be lit evenly and independently. If this canvas is rolled out flat, we have a grid of sixteen rectangles: two high and eight wide so that the patterns that can be generated can be drawn out as shown in the diagram above.

LED colour changing systems can be controlled and programmed digitally so that animation of these coloured cells with rotating and undulating patterns can easily be achieved. Imagine the coloured cells of these grids moving along one by one to rotate the pattern around the Octagon.

At Lincoln the location of the fittings was a more complex task, with many locations reliant on the accessibility of neighbouring rooftops and largely unseen locations in hidden pockets of the cathedral roof areas. Here the canvas maps out in a very different way, as there are just over fifty fittings providing the lighting to the three towers. These are all able to produce coloured light as well as a warm light that matches the conventional white uplighting and floodlighting. So with this arrangement it is easier to light each tower in one colour rather than each face, so the static looks are easy to achieve.

Not all lighting schemes need the addition of coloured effects, with some buildings simply not suited to them. There are arguments against ‘exploiting’ older buildings with colour, and some views are that they should only be lit as though by moonlight. Others say that floodlighting cannot be justified in the current age of high fuel and sustainability costs.

We should also be aware that some schemes of this nature are vulnerable to exploitation by the designers, manufacturers and suppliers of the systems used, simply as very public advertisements for their trade. As an example of this, some decades ago but over a period of many years, the external lighting of St Paul’s Cathedral and London’s Tower Bridge featured widely on the front covers of manufacturers’ catalogues and in multiple advertisements in international press – and even in marketing letters from the electricity suppliers.

The opportunity to design lighting schemes for our landmark buildings is a very great honour, but it should not be taken lightly. The design should treat the building with respect, even reverence. While the design should fulfil the needs and expectations of the of the client body (commercial or otherwise), it should be balanced and proportionate in the knowledge that it is only a transient dressing of the architecture that will surely outlast this generation of technology and the next.