Heritage In Ruins

The Maintenance and Preservation of Ruined Monuments

Robin Kent

|

|

| Lichens contribute to the special character of this ruinous early Christian chapel on the Isle of Tiree, but have also helped to break down the mortar, leaving it in urgent need of repointing. | |

|

|

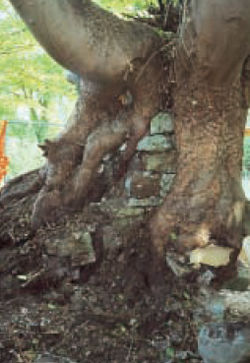

| Vegetation, one of the main enemies of ruins: here, the roots of a mature sycamore have fused with a 15th century wall | |

|

|

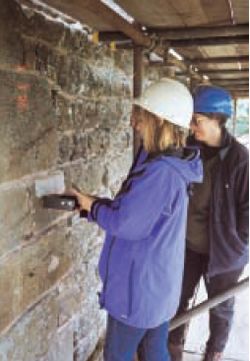

| Using lasers to help record lichen growths on ruined walls before repointing. |

Britain has an exceptionally rich heritage of ruined monuments and a long tradition of caring for them. Military sites, pithead and dockyard structures, mills and other industrial and agricultural buildings which no longer have a sustainable use can be added to a list which includes medieval abbeys and castles. Lying on the borderline between architecture and archaeology, such monuments are usually roofless, often stripped bare of woodwork and other more perishable contents by previous owners, vandalism and the depredations of the weather. Picked bare, their skeletal remains can demonstrate construction and development particularly clearly and frequently provide unique information about the past. Many are picturesque landmarks or spectacular structures in themselves. Some have dramatic historic associations which may encourage speculation and stimulate the imagination in a special way. The encroachment of nature can contribute to their particular attraction and significance by making them specialised natural habitats for rare flora and fauna.

LEGISLATION

Recognition of the special importance of ruins and other archaeological monuments led to Britain's first heritage legislation, the 1882 Ancient Monuments Protection Act. Today the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act 1979 protects around 26,000 'scheduled' ancient monuments in Britain which are considered of national importance, including many ruined ones. Many other ruins are listed and still more are of interest but not yet covered by any heritage legislation. The maintenance of the vast majority remains the responsibility of private owners who, in the case of scheduled ruins, must obtain prior consent for demolition, destruction, damage, removal, repair, alteration or addition, flooding or tipping; the main aim being to avoid anything which could impair their archaeological interest. The Act allows 'class consents' for emergency work and also provides grant aid for repairs, while other grants may be available from the Heritage Lottery Fund, local authorities, heritage groups and amenity societies. Although it is now rare for monuments to be taken into state guardianship, owners who neglect the maintenance of ruins can be held liable for injuries to visitors (including trespassers) under the Occupiers' Liability Act 1984 and if the ruins are listed (but not scheduled) local authorities may compel them to carry out repairs and can compulsorily purchase them.

DECAY

It is sometimes thought that ruined monuments do not require any maintenance, but in fact they can be more vulnerable to decay than roofed buildings which are wind and watertight. Ruined walls without the protection of a roof, render or plaster are subject to the full effects of weathering from all sides. Although decay is often a long-term phenomenon, it progresses imperceptibly but inexorably, usually by a series of 'punctuated equilibria' - small incremental changes which periodically lead to massive collapses.

A ruin which is not maintained will eventually be lost to all but the archaeologists. The agents of decay include wind, rain and frost, which can wash out mortar and erode structural masonry leading to progressive collapse; birds and animals which can burrow into and undermine ruined walls, and woody vegetation which levers walls apart.

RECORDS

Record keeping provides a key to maintaining ruins. Old prints and photographs are particularly useful, as photographs taken from the same positions can show the progress of decay over a long period. Records of previous repairs and maintenance can also be useful.

PROFESSIONAL INSPECTIONS

Quinquennial or five-yearly inspections are the best way to ensure that defects are discovered before irreversible damage occurs. As recommended for all historic buildings in the British Standard for conservation BS7913, the inspection should be carried out by a specialist professional, usually a conservation architect. One advantage of this interval for ruined monuments is that vegetation should not be able to gain too strong a foothold between inspections. Although the inspection can be made from ground level using binoculars, in the case of some ruined walls it may be necessary to provide access so that high level wall faces, cavities and wall heads can be inspected. Mobile platform lifts or 'cherry pickers' can be hired which are mounted on vehicles suitable for rough terrain, providing access to most high walls even on uneven and sloping sites. Other methods, which are also likely to be more economical than scaffolding, include cranes and roped access systems, and one company even offers photographic surveys from a small radio-controlled airship.

A professional inspection will also be the first step if a comprehensive scheme of stabilisation and consolidation is being contemplated, usually followed by a measured survey and photogrammetric stone-by-stone elevational drawings or rectified photography to enable works to be specified. Investigations by archaeologists, engineers, ecologists and other specialists may also be called for and, where ruined monuments are open to visitors, an access audit. These should be brought together in a conservation plan which provides a concise statement of the heritage value of the monument and the threats to its survival, and proposes a policy for its conservation which focuses on preserving and enhancing its significance. The main aim should be to retain all historic masonry material wherever possible and the plan may suggest special protection such as discreet flashings over carved ornamentation, or even re-roofing of specially vulnerable areas of historic importance.

|

|

| Above left: Underbuilding cavities needs to be carried out with great care to ensure that the character of the wall is maintained. Above right: Careful repointing with lime-based mortars is usually a major component of ruin conservation and specialist contractors are required. | |

DEALING WITH VEGETATION

For many ruined monuments where routine maintenance has been neglected, one of the main problems is woody vegetation that has taken a firm hold. Ivy may be a picturesque adornment for ruined walls but its lime-loving tendency and aerial roots can lead to deep penetration, opening up mortar joints and cracking apart walls with remarkable speed. The roots of trees such as sycamores can similarly run for many metres inside the corework of historic masonry. Wind forces on the foliage of such vegetation can lever apart even the most massive walls. If growth remains unchecked, collapses may occur with relative regularity as vegetation regrows, every 20 years or so, reducing even the highest walls to rubble. Such vegetation will require careful pruning to reduce wind resistance, taking care not to damage historic fabric with falling branches. The main stems must then be cut and poisoned using systemic biocides. Only after withering should any attempt be made to remove them from the masonry and even then it may not be possible to wholly remove some roots without a measure of rebuilding.

CONSOLIDATION

|

|

| Cavities used as bat roosts can be identified and marked with coloured crayons to ensure that they are preserved when repointing is carried out. |

Loss of mortar is also a problem for most ruined monuments, as the soft lime and clay mortars with which most historic buildings were built are loosened by soluble salts and frost, scoured out of facework joints and leached out of corework over time. This can lead to accelerating loss of integrity, distortion, bulging and collapse. The usual solution is careful repointing and consolidation using mortars closely matching the originals. Grouting may be needed but is not usually ideal as it can be so difficult to control, as the grout tends to flow anywhere but into the cavities!

Many ruined monuments have been repointed in the past using over-hard cementitious mortars and grouts that have actually accelerated stone erosion. Its removal can cause further damage to the masonry and a limited amount of stone indentation using matching stone may be required to maintain the structural integrity of the wall.

WALL HEADS

Wall head treatments and weatherings are generally crucial for keeping water out of ruined walls. At one time it was thought that wall heads should simply be capped in concrete painted with bitumen, but this was disfiguring and many ruined walls have since been treated by 'rough racking' or 'coring', forming a coping of recreated masonry corework on top of the historic wall. Both these approaches tend to crack and direct water into the walls at specific locations and also have the effect of concentrating water flow down the wall faces, accelerating stone erosion. In recent years there has been a move towards 'soft topping' ruined walls, with turf such as naturally occurs on ruins over time. This absorbs water and insulates the wall head, and can also 'breathe' and dry out: the grass overlapping the edges also provides a natural 'drip', protecting wall faces. Innovative soft tops have been used over the past ten years on Thirlwall Castle, Northumberland and Wigmore Castle, Herefordshire, as well as at Fountains Abbeys, Yorkshire, and have the advantage of retaining the natural appearance and wildlife interest of ruined monuments.

|

|

|

| Above: Roses and other woody vegetation have led to fracturing and progressive collapse of the wall head. Below: To ensure that the soft top retains its authentic character, seeds are collected before stripping the 'natural' soft top and consolidating the masonry. Bottom: Hard cement capping after clearance, showing extensive root penetration into the wall head. | Above: Grass and non-woody vegetation removed from wall heads can be retained on plastic sheeting with hydroponic gel, and watered regularly. Below: Woody vegetation has been removed and the wall head consolidated before the natural grass top is replaced. Wild flowers will follow in due course. Regular attention to maintenance will ensure that shrubs and trees are kept to the minimum. | |

|

||

|

||

|

STABILISATION

Ruins which exhibit structural problems require the services of a structural engineer with specialist experience. Cracking is usually a symptom of a long-term problem and, unless it presents an imminent danger, it should be monitored over at least a year to determine whether it is progressive, and not simply the cyclical product of seasonal movement. Trial pits or cores may be required to establish subsoil conditions that may be contributing to movement. While most cracks can be tied using steel or concrete ties, dropping vaults and leaning or bulging masonry may demand more costly interventions which can exercise the full skill of the engineer.

|

|

| Inadequately supported massive masonry which requires the introduction of new supports. |

The aim must always be to carry out the minimum intervention to render the monument safe. Bulging walls often require rebuilding but can sometimes be stabilised using stainless steel ties. Where timber lintels or beams have rotted away it may occasionally be appropriate to restore timbers if they can be protected from decay. Often the natural arching effect of historic masonry can be utilised to provide 'invisible' support, using built-in stainless steel mesh reinforcement. Cracked stone lintels may require bonding with pins or visible metal or concrete supports, but underbuilding or limited restoration of lost supporting masonry based on historic evidence can be less visually intrusive. Such interventions should always be recorded and discreetly dated to prevent confusion.

USING RUINS

The best way to ensure that a ruin is properly maintained is make use of it. Many ruins have been reroofed and given new uses, but many more remain as ruined monuments: In addition to being visitor attractions of interest to historians and tourists, they can provide romantic settings for weddings, theatre and other leisure activities. This may require clearance of fallen stones under archaeological supervision and the provision of unobtrusive services, facilities and parking, as well as interpretation and other signage. Planting can often be used to blend these in and manage visitors by discouraging access to less safe areas or climbing on low walls, but signs should always remind visitors that ruined monuments are never completely safe. Regular attention to maintenance will help to provide a reasonable response to the special risks that ruins pose.

Important as maintenance is, overzealous attention to maintaining ruins all too often leaves them soulless, manicured and 'neat', destroying the very features that make them special to so many people. Everyone involved in conserving and maintaining ruins needs to retain a sense of perspective and even at times to accept a measure of decay, so that the special natural quality of ruins, and hence their attraction and enjoyment, is preserved and enhanced.

~~~

Recommended Reading

- Ashurst, J & Dimes, FG, The Conservation of Building and Decorative Stone, Butterworth-Heinemann, Rushden, Northants 1998

- BS 7913:1998. Guide to the principles of the conservation of historic buildings. British Standards Institution, London 1998

- Scheduled Monuments, A guide for owners and occupiers, English Heritage, London 1999

- Fawcett, Richard, The Conservation of Architectural Ancient Monuments in Scotland, Guidance on Principles. Heritage Policy, Historic Scotland, 2001

- Scheduled Ancient Monuments. Historic Scotland

- Thompson, MW, Ruins: their preservation and display. British Museum, London, 1981

Author's Note

This article is not a specification. Each ruin is unique and will require individual consideration. It represents a summary only and no responsibility is accepted for errors or omissions.