Trees and the Historic Environment

Sebastian West and Eric Heath

|

|

| Parkland at Wilton House near Salisbury, Wiltshire (All photos: LUC) |

Whether forming an essential part of the rural landscape through forestry and agriculture, or providing a dramatic vista within a designed park and garden landscape, trees have long been valued as part of the UK’s landscape.

Landscape design tastes have evolved over time. Before the mid-18th century, parks and gardens were very much in the formal, architectural and geometric design. For example, trees were laid out in strong axial formal avenues radiating from the principal house and feature points.

It wasn’t until the rise of landscape designer Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown (1716-1783) that trees became an essential instrument in producing sinuous and smooth views with the use of tree clumps and belts among lakes, ponds and rolling pasture. Brown’s idealised landscape then gave way to the Picturesque design movement in the late 18th century, which appreciated the appeal of nature, the rugged and the untamed.

Ancient and veteran trees* conformed to the aesthetics of the fashionable gothic movement. Landscape designer Humphry Repton (1752-1818) was an advocate of the Picturesque style. In his Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1803) Repton recorded that ‘The man of science and of taste will… discover the beauties in a tree which the others would condemn for its decay’.

During the Victorian period the more formal Gardenesque landscape design movement was introduced by Scottish author, botanist and garden designer John Claudius Loudon (1783-1843). This landscape design style was subsequently adopted by many public parks which encouraged the planting of exotics and a range of interesting evergreen specimen trees. The increasing popularity of global travel among the wealthy meant that exciting new species were planted and shown off among fashionable society. Many of these trees survive today in our parks and gardens.

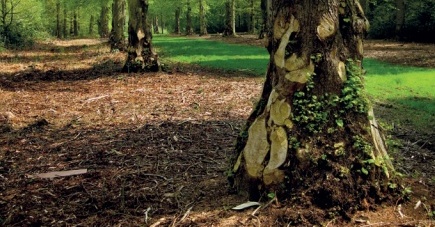

|

|

| Tree showing signs of decline following ploughing almost up to the trunk |

During the early 20th century estates began to be broken up and historic parkland designs began to be eroded. Forestry production also increased along with clear-felling (the harvesting of all or most of the trees in an area of woodland) as part of the war effort. It was not until after the Great Storm of 1987 that people began to think increasingly about repair and conservation of the historic landscape and the trees within them.

Trees provide historic cultural connections with people, events and places. They provide a significant component in the history of the British landscape, providing an aesthetic value that cannot be underestimated. Trees and their layout also help us to understand parkland character and historic management practices including use as medieval hunting grounds, or for forming historic hedgerows, pollards and coppice areas.

The English Heritage Register of Parks and Gardens records those designed landscapes which are nationally important and which represent a material consideration for local planning authorities in determining planning applications. Similarly, there are other ‘non-statutory’ registers which record historic designed parks and gardens for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Tree specimens, hedgerow trees, clumps and larger woodland areas contribute to the inclusion of a landscape in the register, as they will usually have formed part of the original design intention of the landscape designer.

TREES AND BIODIVERSITY

Trees support, and are supported by, an extraordinary range of species. Their interactions with these species are highly complex and much is still to be learned. However, it is worth considering trees as ecosystems in their own right operating within other ecosystems. The ecological resources provided by a mature tree are extensive and range from large cavities in the tree trunk, which provide roosting opportunities for bats; to their vegetative growth, which provides a food source for a plethora of birds, mammals and invertebrates; and their root networks, which support diverse communities of symbiotic fungi.

|

|

| A veteran tree at Ampthill Great Park in Ampthill, Bedfordshire |

The ecological resource provided by a tree depends to a large degree on its setting. Open grown trees are able to realise their full leaf potential and can therefore maximise their pollen and fruit production, providing a huge food resource for a large array of species. Woodland trees exert a large degree of influence on their surroundings, often creating shady and humid environments that are vital for many species.

Virtually every historic park made use of existing trees, which were retained to give an air of antiquity to newly created landscapes. It is probably this retention of existing trees that has resulted in historic parks and gardens supporting a disproportionate number of veteran and ancient trees. The popularity of the Picturesque landscape design movement has almost certainly contributed to the fact that Britain has more ancient trees than most other countries in northern Europe.

An ancient tree is one that has passed through full maturity but only achieves ‘veteran’ status as its structure changes to reflect its age, limbs are shed and decay sets in. The crown of an ancient tree will have reduced in size from its full extent as the tree sheds redundant parts and accumulates dead wood. This reduction in crown size is a process known as crown retrenchment. As a tree ages it is progressively colonised by fungi that can alter the structure and condition of its wood. Natural damage and shedding of limbs and branches can, through the action of wood decay fungi, lead to trunk hollowing, branch cavities, live stubs, shattered branch ends, loose bark and sap runs.

These ‘veteran’ features provide highly specialised habitat niches for a range of organisms. Many of these organisms are characterised as having extremely limited powers of dispersal. Continuity of habitat and lack of disturbance are therefore very important factors in determining the ecological resource that these trees provide.

Although these veteranised features are now recognised as providing an important ecological resource, this was not always the case, and the blight of tidiness curses many historic parklands. Here unsightly growth forms and ‘dying’ trees are removed via overzealous tree maintenance regimes which often damage the trees themselves as well as removing vital ecological niches.

|

|

| In many tree species epicormic buds lie dormant beneath the bark and their growth can be triggered by changes such as damage higher up the tree. The overzealous removal of epicormic growth shown above was presumably intended to create a ‘tidier’ appearance. |

Invertebrates associated with dead and decaying wood are generally of a high conservation value. Many are local or rare and are declining in both Britain and Europe. Dead wood occurs in a wide range of forms, each supporting its own distinctive assemblage of invertebrates and the successful conservation of the biodiversity supported by ancient wood pasture is dependent on the maintenance of a wide range of wood decay situations at site level.

The insects associated with ancient trees commonly have complex life cycles. Different stages of the life cycle may have quite different habitat requirements. Many species that require dead wood habitats in one stage of their life cycle rely on nectar sources for food in another stage. Open structured flowers such as those of hawthorn, umbellifers and composites are particularly important, and the maintenance of scrub and other areas with tall flowering plants can make a very significant contribution to the successful function of a diverse invertebrate community within wood pasture.

MANAGING HISTORIC TREES FOR THE FUTURE

Prevention of ill-health within existing trees and ensuring future replenishment and enhancement of tree stocks should be key priorities within the landscape to prevent any further loss of these valuable assets to the wider historic environment. Production of conservation management plans and parkland plans by landscape conservation specialists can help to achieve appropriate tree and woodland management for future generations.

In terms of tree management, safety is always of paramount importance due to the nature and severity of potential hazards, including falling limbs. It is, however, worth highlighting the fact that many problems can be avoided through good management and measures such as re-routing paths away from dead or dying trees.

|

|

| Landowners have a statutory duty to keep public rights of way free of obstacles such as fallen trees but they also need to consider visitors’ safety. Many problems can be avoided through good management and measures such as re-routing paths away from dead or dying trees. |

All owners and site managers must of course consider the safety of the public and those visiting the area. Trees should have regular inspections by a qualified arboriculturalist to assess the risks. Landowners also have a statutory duty to keep public rights of way free of obstructions including fallen trees and branches. However, dead wood should be retained for the benefit of wildlife where it is safe to do so.

Prevention of damage to trees can be achieved by providing sufficient clearance between trees and machinery or cattle. Vehicle movements over the root zones of trees should be avoided, particularly with mature trees. Materials should not be placed near trees and fertilisers should not be used in their vicinity. Substantial wooden cages should be erected around vulnerable trees at risk of stock damage through compaction or physical damage.

One of the main causes of veteran tree death is branch, stem or rootplate failure. The key aim of any veteran tree management programme should be to enhance tree longevity wherever possible to ensure there is no unnecessary loss of veteran trees. This enhancement of tree longevity can be achieved by improving the structural and physiological condition of the trees.

Where a tree is at risk of catastrophic failure, remedial works can be used to stabilise the tree. Typically these will be targeted to reduce the end-loading on limbs and rebalance the tree. Where trees are assessed as showing signs of physiological stress, management may focus on promoting vitality. This can be achieved by reducing competition for resources around the tree and improving the root soil condition.

Developing a replanting strategy is an important stage to ensure future replenishment of tree stock (including veteran trees) and habitat. It is possible to manage the veteran tree resource through implementation of selected individual veteran tree management plans with the aim of maximising longevity of veteran trees to ensure continuity of habitat and lack of disturbance to maximise the ecological resource.

~~~

Notes

*Veteran trees can be any age. They are trees which are commonly seen as survivors, showing signs of trauma and decay. Ancient trees are those which are old for their species.