Historic Wallpapers

Conservation and Replacement

Robert Weston

|

|

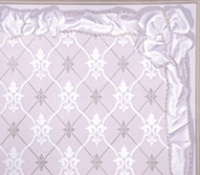

| Modern reproduction of the original French paper (c1850) for The Yellow Bedroom at Uppark, West Sussex |

Exotic wall coverings were used to decorate the homes of the wealthy long before the invention of wallpaper. Available to a select few, they were flamboyant statements of social status as much as decorative finishes. These precursors of wallpaper included coloured and gilded plasterwork, embossed leathers, tapestries, woven damasks or plain expanses of ‘paned’ fabric separated by braid. They shaped the development of paper hangings from the 16th to the early 20th centuries, with fabrics being a particularly strong influence.

The earliest papers were printed on single sheets. The Cambridge Fragment, found in Christ’s College, Cambridge was printed on the reverse of a recycled proclamation issued by Henry VII. It is the earliest known example of English wallpaper, and was probably hung after 1550. Later, a dozen sheets of rag paper would be glued along the edges to form a roll approximately 11 yards long. A ground colour was applied by hand before printing on designs with wood blocks and/or stencils using distemper pigments. This became the formula for English wallpaper production until the early 19th century.

Until the early 18th century, elaborate wood-panelled walls and tapestries were the fashion for those who could afford them. By the mid 18th century a chair or dado rail replaced full height panelling in main reception rooms. Plain horizontal boarding above the dados would have been decorated with woven fabrics ‘strained’ over hessian or canvas around the wall perimeters and held in place by tacks hidden with braid, gilt lead or painted papier mâché fillets, or printed paper borders. Wealth and status were displayed in reception rooms using the costliest fabrics and print or dye colours available. Blue was the most expensive pigment, followed by red and green. Earth colours were the least expensive. Each wall would be treated in the same way and, where possible, the patterns and colours would match the upholstery and curtains.

In the 18th century, fashion filtered down from the wealthy elite through an expanding middle class to those less able to afford domestic luxuries. Wallpapers were hung in the same manner as the velvets, silks and embroidered fabrics they imitated. Perennial choices have been large scale traditional damasks for important rooms and florals or sprigged stripes for lesser rooms. It was not considered too important if the patterns were mismatched, but the effect had to be impressive.

The pre-eminence of English block printing on joined sheets and English design innovation were the envy of the world during the 18th century. The French court began replacing their tapestries with imported English wallpapers. In an early example of industrial espionage, spies were tasked with learning the secret manufacturing methods of Papiers d’Angleterre or flocked and lustre papers. Designs were first block printed with a coloured adhesive on a hand-painted ground colour over which very finely chopped dyed wool (for flock) or powdered mica (for lustre papers) was sprinkled to imitate cut velvet or silk brocades. The vibrant colours and textures, designed to be viewed by candlelight, would have been stunning. Some of the original colours and combinations would seem garish to modern tastes and the much-faded examples that survive can only hint at their once vivid impact.

Hand-painted Chinese papers sold in sets were introduced via the East India Company and imported from the early 18th century onwards. More delicate in design and detail than block prints, they featured non-repeating designs of birds, butterflies and foliage or scenes from daily life and were typically favoured for more private rooms such as bedrooms and boudoirs. Extremely highly prized commodities, these papers were often installed on linen over wooden frames for ease of removal.

By the 19th century, panelling had become unfashionable and flat walls down to the skirting were preferred. Projecting mouldings were either removed or hidden by reusing the panels with the face to the wall. Plastering over panelling offered rudimentary fireproofing, but another common practice was to hide it behind wallpaper. The first step was to tack linen or canvas over the entire wall, covering recessed panels to give a flush surface. This was followed by a heavy cartridge lining, then paper, no longer tacked but pasted to the wall. The printed paper or plain painted walls were finished with wider borders that no longer served a functional purpose. Once this foundation was laid, subsequent decorative layers would be added without stripping back, gradually building up to give the appearance of a solid wall. The entire ‘sandwich’ can be removed as a unit relatively easily and quickly in a dry state supported on the canvas substrate for delaminating and conservation. As many as 27 layers of paper have been salvaged in this way.

|

|

||

| Above left: In situ conservation of wall-hangings in a privately owned castle near The Hague, The Netherlands. The wall-hanging in the background is an early 18th century block-printed and flocked linen (Photo: Elsbeth Geldhof / Blue Tortoise Conservation). Above right: Mid 18th century interior with original coordinating block-printed fabric and wallpaper in indigo on white showing the extremes of dilapidation sometimes encountered. The wallpaper could be conserved but the fabric would have to be remade. | |||

English wallpaper manufacture was heavily taxed from 1712. The removal of this tax in 1836 coincided with industrialisation and huge strides forward in mechanical production. Continuous paper making and multi-colour paper printing machines were developed from calico fabric printing. By the mid 19th century, wood pulp and straw-based papers, replacing rag paper, made the cheapest machine prints available for use throughout the house including servants’ rooms. Costs were falling but the quality of British design was also deteriorating.

The French, meanwhile, concentrated on hand block printing and by the early 19th century they had become the European masters. Many recently independent Americans preferred purchasing from the French, selecting intricate swagged fabric effects or panoramic papers which required hundreds of blocks to create. Eventually, quality English hand block printing as a craft would be revived by William Morris and other designers involved in the Arts & Crafts Movement.

Enormously wealthy late Victorian and Edwardian industrialists favoured revivals of the earlier Italianate or ‘Jacobethan’ styles: wall treatments featuring wide decorative multicoloured printed borders and gilded friezes above a picture rail or elaborate panelling. Manufacturers developed various deeply embossed processes, enabling them to produce papers that resembled plaster or leather which were both durable and washable. Lincrusta and Anaglypta are two of the better known survivors of this period, but few of the traditional designs are still available.

Generally, all four walls of a room were treated in the same manner until the first world war swept the old orders away. Tastes explored new asymmetrical treatments in architecture and interiors combining paint, paper and feature walls together with exotic friezes and bordered areas.

Large numbers of early wallpapers have survived and they are still being discovered. However, many have been lost during redevelopment projects on historic buildings. Architects and builders may be unaware of the layers of paper archaeology hidden within what appears to be painted plaster or hardboard that is stripped out to make way for new finishes.

|

|

| Above: Reproduction paper in situ in a house in Lillesand, Norway, which was built by a 19th century shipping magnate. Below left: fragments of the original 1850s paper uncovered in the house and, beneath, the hand screen-printed reproduction paper commissioned in 2009 by the great grand-daughter of the original owner. |

CONSERVATION

Wallpaper conservation in a historic house may entail work on a complete room of surviving wallpaper or attention to a few worthy fragments. All papers may require cleaning or repair. The principal causes of deterioration are fluctuations of temperature and humidity, pest infestation, exposure to sunlight and atmospheric pollutants, or acidic reactions within the pigments, paper or substrate. In any of these situations or following a disaster such as a fire or flood, the advice of trained wallpaper conservator will be invaluable.

Work on small areas that need surface treatment and repair can occasionally be carried out in situ but this will not allow access to the back for additional investigation. The most thorough treatment for very badly affected papers is their complete removal, supported on the canvas backing if possible or detached from the wall by other methods. The front and back of the paper as well as the wall can then be treated as required with surface cleaning, consolidation of flaking pigments or delaminating paper and de-acidification before it is relined with a historically appropriate, conservation quality material prior to re-hanging.

REPLICATION

Where original schemes have been substantially or totally lost, infill or replacement can be considered. If enough of the original paper or photographic evidence survives, the original can be closely replicated. Alternatively, written evidence may be helpful in sourcing a replacement pattern of an appropriate style, date and colour.

|

||

|

The cost of recreating small quantities of wallpaper should be considered carefully in relation to the overall budget of the project. Production techniques and materials, the number of colours used, the conditions to be replicated and how they can be achieved in facsimile, will all need to be assessed.

Earlier hand blocked designs are the most straightforward to produce. They are often printed in just one or two colours on a hand brushed ground. Distemper inks give a slightly chalky look and a raised effect is created by the suction of the block being lifted off the paper.

A number of earlier production methods or materials are either not available for modern health and safety reasons, or are prohibitively expensive over a small production run. The synthetic fibres used in modern flocking bear little relationship to the look and feel of their 18th century counterpart, and a number of basic colours used before 1860 were formulated with highly toxic compositions involving arsenic or lead. Machine-produced papers, however, may incorporate various applications developed during the 19th and 20th centuries which are now difficult to replicate. The cast metal embossing rollers once used to produce thousands of rolls of wallpaper have mostly been scrapped or recycled. Surface print rollers remain in use, but this method of mechanical printing is geared to mass production and the process does not offer a viable option for producing the quantity needed for a single room, typically between seven and ten rolls.

Screen printing, developed during the 1930s, is probably the most straightforward alternative for small runs. It also usually requires one screen per print colour but this method has an advantage: using thinner inks through the mesh, it can produce subtle textural elements or create additional mid-tone third colours with overlays, saving on screen-making and printing costs for multicolour designs.

The photographic technique of digital printing developed for computers is the latest and most economical method being used for both wallpaper and fabric. Very small runs can be set up without production of waste materials. The finished effect can look flat and slick, perhaps not ideal for replicating a traditional paper to be viewed at close range, but the results are improving rapidly.

The purist’s approach would be to reproduce a paper as faithfully as possible, meticulously imitating the original artwork, printing with carved pear-wood blocks and analysed pigment colours onto joined handmade and grounded paper. This is time consuming but it is the best way if only one wallpaper is involved. However, a project with a suite of rooms to recreate would require a substantial budget or perhaps giving up some papers in favour of simple paint schemes.

An alternative approach would be to recreate designs using a combination of traditional and contemporary techniques to produce modern papers that are at least sympathetic to the originals, but easily distinguished by historians and conservators. For example, by hand printing with laser-cut blocks on continuous paper, or screen printing, considerable savings can be achieved. In this case, the primary objective is for the viewer to feel that the paper is correct in its setting, enabling an interior to be presented in a manner that is close to the original in concept.

Artwork and layout copied from the old design is best drawn by hand to capture textural variations and irregularity that are important in the original. The line quality of computer generated artwork can be quite static. First the design unit to be repeated over the paper is established. Each colour to be used is next drawn or ‘separated’ onto a sheet of clear film where accurate overlays can be adjusted as they build up, including any additional patina or embossing effects required. Once the separations are complete they are sent for block carving or ‘stepped up’ into additional repeats for screen making before printing.

CASE STUDY 1: AN 1850s SILK-EFFECT PAPER

|

||

| Screen-printed reproduction of the Trellis and Ribbon Border papers for the National Trust at Uppark: the scale and colours were taken from a small fragment of the original paper found in a shoebox, while the border was recreated from photographs with the aid of a magnifying glass | ||

|

||

| Hand screen-printed reproduction wallpaper commissioned by the National Trust: the paper replicates the patina and faded state of the Tapestry Room wallpaper before the 1989 fire at Uppark | ||

|

||

| A fragment found behind a painting showing the original unfaded colours of the machine-printed wallpaper (c1850) in the Tapestry Room at Uppark |

A French or German wallpaper installed in a Norwegian drawing room by the current owner’s great grandfather in around 1850 was recently found under several layers of later finishes. The paper was a watered silk effect on duck egg blue ground, over-printed with delicate bouquets of wild roses and grasses alternating with bud sprigs. These had been block printed in metallic gilt leaf then finely engraved by metal block or plate to create a shimmering light and shadow effect depending on the angle of view. The original production method was expensive and relatively short lived as few examples appear to have survived in Europe or America.

Metal embossing was prohibitively expensive, but the delicate gold detail can be partially simulated today by screen printing. Two screens were needed for gold highlight and shadow with a third light printed moiré or rippled effect on the darker duck egg ground. The floral motifs were first photographically enlarged to exactly 1.5 times actual size for tracing by hand using a pen of the correct nib size. The shadows of darker gold, which formed the first colour print, were drawn on clear film, followed by a second overlay for the bright gold embossed horizontal lines. Both were then reduced back to actual size to achieve the scale and delicacy of the original before vertical and horizontal repeats were created across the width of the screens for printing.

The original paper had been hung incorrectly and was reinstated in the same manner: the design should be hung as a half drop with the large bouquets staggered, not side by side.

CASE STUDY 2: THE UPPARK PAPERS

After a disastrous fire gutted Uppark, a magnificent late 17th-century house in West Sussex, the National Trust commissioned Hamilton Weston Limited to recreate five of its original wallpapers and one border as part of the extensive programme of restoration. Most of these were in the private family apartment on the first floor. A sixth wallpaper was printed by Farrow and Ball and Allyson McDermott was responsible for the conservation, rehanging and insertion of recreated portions of the Red Drawing Room’s flocked wallpaper.

Photographs of each room had been taken before the fire for insurance purposes showing architectural elements as well as wallpapers. These visual records were extremely useful in reconstructing the lost designs. Painstaking research revealed a variety of other useful sources.

A nearly complete repeat of the Yellow Bedroom paper in original colours was traced to the Musée Forney in Paris. The original 21 colour hand blocked paper (c1850) was reproduced by screen printing. Mid tone colours were achieved by overlaying light over dark, reducing the number of screens required to 14, considerably reducing production costs. A full size photograph obtained from the museum was invaluable for colour separations, while the missing section of the pattern was reconstructed from the Uppark insurance photos using a magnifying glass.

A record photograph of the family dining room on the first floor showed the trellis paper and 1840s ribbon border used continuously around the perimeters of the room. The photo had been taken obliquely into one corner and showed separate elaborate corner bows. Recreating the full five colour repeat of border and corners while compensating for distortion was possibly the most difficult design problem the project presented. Photographs of both the paper and the border showed dull grey tones but the lucky discovery of a fragment of the paper in a shoebox determined the complete restoration of the room in delicate shades of mauve. Two further bedroom papers were traced to the Victoria & Albert Museum’s wallpaper collection. Many off-cuts from the papers used in the house had been donated to the museum by the family some years before.

At the end of the project, family members were thrilled to see the familiar wallpapers in place in rooms that had seen all other contents and finishes destroyed. The wallpaper reproduction project at Uppark demonstrates the value of systematic recording procedures and meticulous historical research. Combined with a little good fortune, these efforts allowed Uppark’s lost historic interiors to be faithfully recreated.

~~~

Recommended Reading

- G Beard, Upholsterers and Interior Furnishing in England: 1530–1840, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1997

- L Hoskins (ed), The Papered Wall: The History, Patterns and Techniques of Wallpaper, Thames & Hudson, London, 2005

- M Miers, The English Country House: From the Archives of Country Life, Rizzoli, New York, 2009

- RC Nylander, Wallpapers for Historic Buildings, Preservation Press, Washington DC, 1992

- T Rosoman, London Wallpapers: Their Manufacture and Use 1690–1840, English Heritage, London, 1992

- G Saunders, Wallpaper in Interior Decoration, V&A Publications, London, 2002

- C Thibaut-Pomerantz, Wallpaper: A History of Style and Trends, Flammarion, Paris, 2009

- P Thornton, Authentic Décor: The Domestic Interior 1620–1920, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London,1985

For more information on this subject, please visit the Wallpaper History Society’s website: wallpaperhistorysociety.org.uk.