Infill Panels

Two Denbighshire case studies demonstrate common problems and typical solutions

Geoff Broster and Carol Thickins

|

|

| Nantclwyd House, Ruthin (above) following restoration and (below right) one of the many repairs carried out to the timber frame. |

Shropshire and the surrounding counties are fortunate to have a large number of surviving timber framed buildings. This good fortune is enhanced by the wide variety of building types and styles and the variation in methods of construction of the timber frame structures over a long period of time.

Early infill panels are generally either of wattle and daub or, as at Nantclwyd House, of oak staves and woven laths with a lime plaster or daub finish. The wattle typically consists of oak staves with woven hazel twigs, and the daub is likely to contain (in very variable proportions) clay, lime and a mixture of cow dung and straw. Brick is also common, but this is usually a later insertion after earlier daub has failed or alterations have taken place, and is traditionally set in a lime mortar. Of these, daub and lime plaster are most likely to be original and are best suited to timber frame construction because they absorb and release moisture relatively quickly. This allows the frame to breathe and reduces the risk of moisture being trapped against the timbers causing decay.

The most important issues to be considered before embarking on the repair of infill panels include, first, discerning whether the existing infill panels are original or, if not, whether they have developed historic significance in their own right. Second, it is also essential to consider the condition of the panels and of the adjacent framing, and, particularly in the case of the replacements, whether the framing has been adversely affected by the type of panels used.

|

In addition to these issues, and in the light of modern requirements for conserving energy, decisions also need to be made on whether to improve the thermal performance of the infill panels and, if so, how insulation can be introduced without harming the historic fabric. These issues are illustrated in commissions which Donald Insall Associates has recently received to undertake repair and restoration projects to two timber framed buildings in North Wales for Denbighshire County Council; Nantclwyd House and the Tŷ Coch barn. Both projects included repairs to infill panels, the reinstallation of missing sections of framing, and the relocation of external doors to their original positions.

The two buildings are about five miles apart and, according to dendrochronological evidence, both were constructed in the early 15th century. This area of the UK is rich in timber framed buildings of this period, and similar dates have been returned from the analysis of a number of other examples in the surrounding area. However, their similarity ends there: the two buildings have very different functions and forms of construction.

HISTORIC BACKGROUND

Nantclwyd House is a Grade I listed building in Castle Street, in the centre of the ancient market town of Ruthin. Occupancy of the house has been traced back to 1435, but the change in its status came in 1490 when John de Grey, who held the Lordship of Ruthin, granted it to John Holland. Since then the building has passed through several owners in its life.(1)

The earliest part of the building comprises the substantial remains of a medieval three-unit timber framed house with hall and flanking cross wings. As is usual for buildings of such age, extensive alterations had been carried out over the centuries. In this case it is thought that the majority of these date from the second half of the 17th century when Eubule Thelwall enlarged the house, bought Lord's Garden at the rear, and constructed a large summer house in it. However, it seems likely that the north-west range is an even earlier addition than this. Most of the extensions are timber-framed structures, except for the substantial west wing which is constructed mainly in stonework.(2)

In the 18th century, the Wynne family extended the parlour and remodelled many of the rooms. The most recent private owner was Samuel Dyer Gough who purchased the house in 1934 and undertook a great deal of restoration work. It was his widow who finally sold the house to the county council in 1984.

|

|

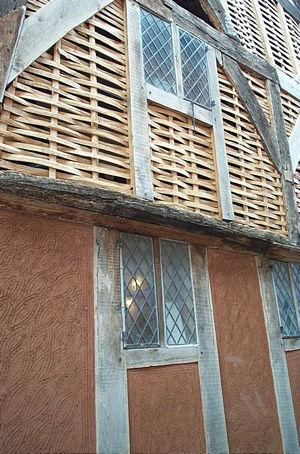

| Reinstatement of traditional split oak lath and daub render panels at Nantclwyd House: the upper storey awaits its daub finish |

The house has seen a wide variety of uses. Originally a town house for wealthy and influential owners, during the 19th century it was tenanted, accommodating a girls' school between 1886 and 1893, and it subsequently became the rectory for the neighbouring parish of Llanfwrog. Between 1834 and 1970 part of the house was also used as judges' lodgings.

The history of the Tŷ Coch barn is less well documented. The barn is in the village of Llangynhafal to the north of Ruthin, and the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales believes that the building was originally constructed as a 'house and byre' of, significantly, five bays (rather than the more usual four bays) using six cruck-trusses, four of which remain. It is thought that the timber box frame replaced the original outer walling in the 18th century, and the trusses were adjusted then, but not moved from their original locations. The building appears to have remained in use as a typical agricultural structure since then, although modified and adapted over the years.(3)

RESTORATION AND REPAIRS

Donald Insall Associates' approach to restoring both buildings has been to combine an understanding of the historical development of each building with a detailed assessment of the condition of its fabric and to use this to inform the extent and detail of the repairs. As a result, the timber box frames and cruck trusses have been sensitively repaired mainly in oak with the minimum of disturbance to the existing fabric and the least possible removal of timber. In places, some more modern repair techniques have been used to effect sound construction joints, in order to avoid removing excessive amounts of timber. Generally, these have involved stainless steel plates and brackets fitted carefully and, wherever possible, in concealed locations.

Nantclwyd House retains two forms of panel infill: interwoven hazel wattle and also split oak staves and laths, both being covered with traditional daub. Following discussions with the conservation officer and Cadw, it was agreed that the existing panels would be repaired as necessary using similar materials to the existing, but where new panels were required, such as where the frame had to be reinstated or where inappropriate earlier repairs had been removed, these would be infilled using split oak staves and split oak laths.

Other alternatives for repair of the panels were briefly considered by the design team, including the use of stainless steel mesh and composite insulation panels, but it was quickly agreed, following discussions with Cadw, the conservation officer and the historical and interiors consultant, that it would be most appropriate to reinstate the panels using one of the original methods. The use of oak staves and laths was preferred as oak lath has greater durability than wattle. (Being all sapwood, hazel wattles are particularly prone to beetle attack.)

Where new infill panels were required, the oak staves were inserted into the existing stave holes in the underside of the timber at the top of a panel and then sprung into grooves in the timber below. The panels gained considerable rigidity as the laths were woven in and pushed down.

The daub or lime plaster was then applied from both sides simultaneously so that it bonded in the centre where the two materials met. The panel was then finished with a lime plaster skim coat neatly scribed into the edge of the timbers.

The mix for the daub used was clay, chopped straw and lime. The use of cow dung as an ingredient was not considered to be necessary and was omitted. It was essential to keep the daub damp and well protected during the curing period to prevent the daub shrinking excessively and cracking occurring. This was achieved by using wet hessian.

Some advantages of a traditional panel of this type are that:

- the thickness of the daub/plaster can be adjusted to cope with variations in the shape and thickness of the framing where less than perfect timbers have been used

- over the years, as timbers move or suffer degradation, gaps around the edges of the daub and plaster panels can be filled with a lime putty

- if hairline cracks in the plaster did appear, they could be filled simply by the regular application of limewash, as is traditional.

|

|

| A section of the cruck frame of Tŷ Coch Barn near Ruthin, prior to restoration commencing | |

|

|

| Part of the north elevation of the barn illustrating the poor condition of the frame: part of one of the cruck blades is visible. |

At the Tŷ Coch barn, holes and grooves are clearly visible in the remaining framing, but unfortunately none of the original infill remains. Most of the panels had been infilled using bricks of a variety of sizes, some of which appeared to be medieval, and may have been the recycled remains of an earlier chimney stack or other feature. They were almost certainly introduced at a much later date, probably in the mid 19th century when the farm complex was enlarged. The end walls of the barn were also reconstructed in stone, probably at this time.

The condition of the external timber box frame at Tŷ Coch was poor, particularly at low level where layers of accumulated dung have accelerated decay of the baseplate. It was therefore necessary to remove all of the brick infill panels in order to repair the frame, with the bricks being set aside for possible reuse. However, the use of brickwork poses a number of problems:

- Traditionally, brick panels relied purely on friction to hold the panels into the frame. They can therefore become unstable if there is movement in the frame. (This can be mitigated by the use of mesh reinforcing strips in some courses pinned to the sides of the framing, but this is still less secure than a woven panel.)

- There is also a tendency for the bricks to hold moisture against the edges of the frame, leading to decay at these points. This is made worse if the brickwork is either built or repaired using a cement-based mortar.

- Bricks also add weight, which may become a critical factor if timber sections are slender or have been subject to some degradation.

- If the framework has distorted (or includes irregular shaped decorative panels) a considerable amount of cutting or packing may be necessary. This is the case with the panels found at Tŷ Coch.

Further research is currently being undertaken before a final decision is made on the type of infill to be used here, but it is likely to be split oak and laths with traditional daub, which is more suitable for the fairly slender timbers found in parts of the wall-framing.

INSULATION

Any requirement to meet modern standards of insulation must inevitably be heavily influenced by the proposed end use of the building, which differs greatly in each of these two cases. The decision also needs to take into account the internal appearance of the external walls and the standard of comfort required.

Nantclwyd House is to become a museum and visitor attraction, with each room depicting a particular period during the life of the building. Internal finishes are therefore now of painted daub with exposed timber or restored and refitted timber panelling of the appropriate period, with some rooms papered on lime plaster finish (where oak laths have been used). Here the standard of comfort takes a lower priority since the building will be minimally heated, and most users will be passing through.

The Tŷ Coch barn, on the other hand, will be let for office accommodation. Although wattle and daub may have been a reasonable insulator for its period, modern requirements are much greater, so here the walls will be dry lined internally using a modern insulating system which will be fixed independently from the timber framing. This allows the external infill to be reinstated in a historically appropriate method, and the modern insulation element is fully reversible: that is to say that it could be removed without affecting the historic fabric further. Windows and doors will also be introduced into the panels as carefully and unobtrusively as possible without disturbing the existing structure and leaving the frame 'expressed'.

We therefore have two very different timber framed buildings passing into the next phase of use in their life, carefully adapted to ensure that they can be used and enjoyed with the least possible impact on their historic character.

~~~

Notes

The following reports have been used as sources of information on the history of the buildings:

(1) CJ Williams, Nantclwyd House, Ruthin, A History for Denbighshire County Council, 2005

(2) R Morris, Nantclwyd House, Ruthin, An Outline Archaeological and Architectural Assessment. Mercian Heritage Series No 172, 2002

(3) R Suggett, report on Tŷ Coch in the National Monuments Record for Wales, July 2006