Europe’s Jewish Architectural Heritage

and the work of the Foundation for Jewish Heritage

Michael Mail

STANDING ON the bimah of the Great Synagogue of Slonim in what is now Belarus is a profound and moving experience; the ghosts swirl, someone in our group is crying.

The Nazis set out not just to annihilate the Jewish people, but also to destroy their culture, consigning their very existence to oblivion. In places like Slonim you feel that they succeeded. Nothing is taught today in the local schools on the Jewish history of the town and the local museum does not mention the Holocaust, yet Slonim in 1939 had 17,000 Jews in a town of 25,000. It was a thriving Jewish centre noted for its Rabbis and scholars, including a famed Hassidic dynasty. Very few survived the mass executions that took place during World War II, brutally extinguishing a community which stretched back centuries.

The only surviving witness to this Jewish history is the Great Synagogue itself. Built in the 1640s, it remains a brooding presence in the centre of the city – shattered, yet majestic. Following the war it was used to store furniture but for the last 20 years it has lain abandoned.

So what do we do with the Great Synagogue, with all these synagogues across the landscape of Europe that so tragically lost their communities of users?

There are many who will question why we should bother with buildings that can no longer serve their purpose. Yet the Jewish presence in Europe goes back over 2,500 years. The Jewish people evolved a distinct and rich culture which made a unique contribution to wider European civilisation and remains a remarkable legacy to this day. Jewish heritage sites – synagogues, Jewish quarters, communal buildings, cemeteries and monuments – are repositories of Jewish life, art and customs. Many are unique and beautifully constructed reflecting real architectural and artistic accomplishment.

The Jewish story in the 20th century became one of transitions, with massive and often tragic population loss and displacement, culminating in the catastrophe of the Holocaust. In the 19th century, nine out of ten Jews lived in Europe, today it is one out of ten. In countries such as Poland and Lithuania which were once the heartlands of the Jewish people in Europe, entire communities have largely disappeared and the architecture of the places they lived and worshipped has become the last testament to a vibrant Jewish past. If this heritage disappears, it will mean there will be no physical evidence of Jewish existence.

By saving this heritage we remember, celebrate and honour these lost Jewish communities. These sites offer invaluable insights into Jewish life and its impact on wider society, and they can be used as powerful places of education. Crucially, they can help build greater understanding and empathy, while also combating the worrying tide of prejudice and intolerance which is re-emerging across Europe. Jewish heritage can be used to serve an urgent contemporary purpose.

This is the view that drives the work of the UK-based Foundation for Jewish Heritage which was established to work internationally on the preservation of Jewish heritage. It has attracted distinguished support and its Trustees include Sir Simon Schama, Lord Daniel Finkelstein, Dame Helen Hyde and the Rt Hon Jim Murphy and features as Friends Sir Anish Kapoor, Lord Julian Fellowes, Stephen Fry and Simon Sebag Montefiore. It also has 57 heritage specialists serving on its International Advisory Panel.

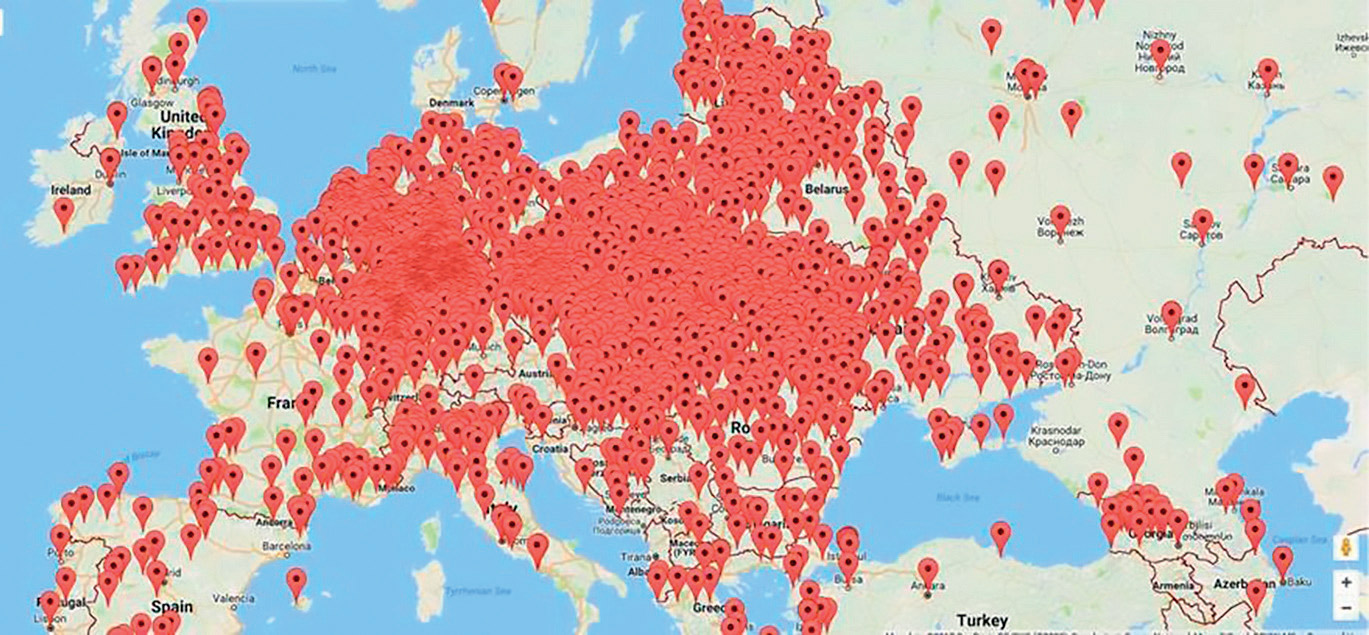

Ground breaking research undertaken by the Foundation for Jewish Heritage led to the production of a map charting all extant historic synagogues in Europe. Each surviving building has been rated in terms of condition to identify those most at risk.

The Foundation took the early decision to focus its efforts on synagogue buildings. These are the most emblematic feature of Jewish communities and much more than simply a place of worship. The synagogue was the main public space of the Jewish community and its symbolic representation. Jews and wider society assigned the synagogues special importance as the embodiment of Jewish communal and religious life.

The urban situation and exterior appearance of the synagogue often reflected the position of the Jewish community within the structure of local society, ranging from assimilation to ‘ghettoization’. Cultural assimilation became more prevalent with the Enlightenment which brought Jewish emancipation to Europe. During this period synagogues went through a major visual transformation as Jews sought to demonstrate that they were now full European citizens, often deciding that the synagogue should match the church in look and splendour.

As a first task, the Foundation therefore commissioned unprecedented research to map all the historic synagogues of Europe. Importantly, this included rating each in order to identify the most important sites in greatest danger.

The research identified 3,237 historic synagogue buildings remaining in Europe today, compared to 17,000 synagogues on the eve of World War II – less than one in five. Of those that had survived, 757 – nearly a quarter – were in sufficiently poor condition to be deemed at risk, with only 718 still functioning as synagogues: more than three-quarters are being used for other purposes or are abandoned.

Since the main architectural characteristic of the synagogue is its large prayer hall, it is a highly adaptable building type. The survey found that those no longer serving their original function had been put to a wide variety of uses, from places of worship for other faiths to cultural, domestic, and commercial premises. Regardless, 300 former synagogues stand today abandoned.

The percentage of synagogues that survived the war significantly differs from country to country and, in general, it is much lower in the east of Europe compared to the west. Especially tragic was the fate of former synagogues in countries under communist rule where many were demolished, reconfigured, or left derelict.

Although the state of preservation is significantly better in the west, reduced Jewish communities have often struggled to maintain numerous synagogues. In Britain, unaffected by the Holocaust, the migration of the Jewish population from smaller to larger cities and from city centre neighbourhoods to the suburbs has left many historic synagogues neglected, sold and in some instances demolished. A prime example of this shift can be seen in Merthyr Tydfil in Wales.

In the 19th century Merthyr was the industrial powerhouse of Wales and its largest town. There had been a Jewish presence here since the 1830s and the construction of a synagogue in the 1870s reflected a community that was growing and prospering. Today, the building is Grade II listed, and is not only the oldest purpose-built synagogue in Wales but it is also considered to be one of the UK’s most important architecturally.

However, the region’s economic decline in the 20th century impacted the Jewish community too, leading ultimately to its demise. The synagogue was sold in 1983 and used for various purposes, but for the last 16 years it has been lying empty, its condition deteriorating to the extent that it became formally designated as at risk. The Foundation recently stepped in and bought the building with the widely supported idea of restoring it and creating a Welsh Jewish Heritage Centre that will present the special 250+ year history of the Jews of Wales and provide a new cultural venue for the town.

There are also historic synagogues with active communities that have recognised that they can make a wider contribution to society going beyond simply being a place of worship for its congregants, like the remarkable Garnethill synagogue in Glasgow.

Garnethill synagogue, situated in the city centre, is a stunning grade A listed Victorian ‘cathedral’ synagogue and the jewel of Scottish Jewry. It is currently in the process of becoming the base for a Scottish Jewish Heritage Centre, with the bulk of funding provided by the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

The Centre will present the history and contribution of the Jewish community in Scotland, and explore issues of diversity and cross-cultural understanding. In addition, reflecting the important mid- 20th century history of Jewish refugees to the city, the project will also contain within it a dedicated Holocaust-era Study Centre that will be an important resource available to schools, colleges and universities throughout Scotland.

The traditions of the ancient Jewish community of Turkey is now essentially Sephardic. This is a result of the Ottoman Empire absorbing a huge influx of Jews in the 15th and 16th centuries following their traumatic expulsion from Spain in 1492. This Sephardic Spanish influence can be seen most profoundly in the magnificent synagogues that were built, and nowhere more strikingly than in Izmir.

The Etz Hayim synagogue is the most ancient of a cluster of nine beautiful Sephardi synagogues in the old quarter of a city of almost 4.5 million. The Foundation is supporting efforts led by the Israeli-based Kiriaty Foundation to save the Etz Hayim. The project forms part of a broader vision to restore all the historic synagogues of the city and create a ‘Jewish Cultural Quarter’ as a visitor destination with a museum at its heart.

The Foundation’s work has entailed following the trail of the Sephardi Jews back to pre-expulsion Spain.

The former synagogue in Hijar in Aragon dates from the medieval period, and is one of the very few pre-1492 synagogues to have survived. Recent archaeological research has revealed astonishing wall murals from that time not found anywhere else in the country.

After the expulsion the synagogue was absorbed into the Catholic church and for the last 500 years its former role was a hidden history. Today the building is used for church services only once a year and the Mayor, along with local activists, would like to re-purpose the site as a Sephardic heritage educational and cultural centre documenting, memorialising and celebrating its medieval Jewish beginnings.

The Council of Europe recently undertook research into the state of Jewish heritage preservation today across Europe, and the Foundation was appointed the expert body to assist this process. The Report approved by the Council’s Parliamentary Assembly highlights the issues and the challenges as well as the opportunities afforded by these sites and ends with a number of important recommendations. Its conclusions include the following comment –

Jewish cultural heritage forms an integral part of the shared cultural heritage in Europe and therefore requires a common responsibility to preserve it. By ensuring the survival of Jewish historic sites, collective memory would also be preserved. Valuing and having a deeper understanding of Jewish culture and heritage, which reveal significant cross-cultural exchanges and mutual enrichment with other cultures, will also contribute to inter-cultural dialogue, promoting inclusiveness and social cohesion, and combating ignorance and prejudice.

The Foundation for Jewish Heritage exists to play its role in saving Jewish history. We want to find solutions for these historic buildings that can bring them back into use, and in a way that serves educational purposes, for the benefit of the Jewish people and wider society. We are dealing with the past, but are future focused, taking buildings that had become meaningless and making them meaningful once more.

Buildings are stories, and these stories – dramatic, tragic, profound and glorious – are vital for our world of today.