Ledger Stones

Julian Litten

|

||

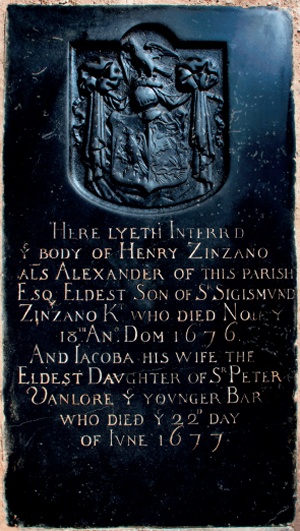

| Zinzano ledger stone of 1676 at Tilehurst, Berkshire: a fine ledger with carved armorial (Photo: Julian Litten) |

If your church was built before 1800 there’s every possibility that it contains at least one ledger stone, a large black or white marble slab set into the floor and inscribed with the names of those interred in the brick grave beneath.

Sometimes known simply as ‘ledgers’, they can be highly decorative, incorporating the deceased’s armorial bearings, while others have a funerary motif such as an hourglass with wings or a death’s head wearing a laurel wreath. Most, however, consist simply of an inscribed legend without attendant relief-sculpture. Whatever form they take, the genealogical information they bear is of paramount importance.

INTRAMURAL BURIAL

As a rule of thumb, ledger stones began appearing in churches in the 1620s. However, it was during the Commonwealth (1649-1660), when faculty jurisdiction was suspended, that the middle classes looked to the interior of their parish church as a place of secure burial. Permission for intramural burial would be sought from the incumbent, the individual deemed the most worthy arbiter of suitable candidates for such a privilege.

With the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 the practice of intramural burial was so established that the ecclesiastical authorities thought it best not to interfere, apart from requiring a faculty for the creation of a brick grave or vault (often simply a double width brick grave) and for the laying of the ledger stone, although in practice such faculties were rarely sought.

We shall never know precisely how many bodies have been buried within our medieval parish churches because burial registers were not introduced until 1538 (and most churches did not take up the practice until legally required to in 1598). Few burial registers, however, give the location of the burial unless it was in the large dynastic vault of a noble family.

Nevertheless, a hint as to the differentiation between those buried in the church and those in the churchyard can be found in the burial register entries because those individuals afforded intramural burial almost always appear with a title of courtesy. Thus a ‘John Smith’ or a ‘Janet Smith’ would be churchyard earth burials, whereas ‘Mr John Smith’ or ‘John Smith Esq’ and ‘Mrs Janet Smith’ or ‘The Hon Mrs Janet Smith’ would be intramural burials.

With hindsight, understanding the usage of a church as a place for intramural burial would have been made much easier had Ralph Bigland’s recommendations of 1764 (see Recommended Reading) been carried out:

Many grave-stones are often half, and others wholly covered with pews, &c. many also are broken, and by the sinking of graves not only inscriptions are lost, but the beauty of the church defaced; all these and many other evils might be remedied, in case every parish was obliged to have, in like manner as abroad, a monumental book, under the inspection of the minister officiating; for which purpose a fee should be paid: nor would it be amiss, if every parish had the ichnography of the church on a large scale, with proper reference to each person’s grave or family vault. This ought especially to be done when any old church is repaired, or pulled down in order to be rebuilt. (p79)

|

|

| Densely packed ledger stones in the north choir aisle at Norwich Cathedral (Photo: Roland Harris) | |

|

|

| 18th-century ledger stones in the Church of St Thomas and St Edmund, Salisbury: chipped edges often resulted from the use of crow-bars to reopen a vault after the original burial. (Photo: Jonathan Taylor) |

Intramural burial was an expensive exercise. In addition to the fee paid to the incumbent for the privilege, one has to consider the cost of digging the grave, lining it with bricks to a depth of, say, ten feet for two coffin deposits, and the purchase, lettering, transport and laying of the ledger stone. Translated into today’s prices this could cost up to £25,000, which was a substantial outlay on the part of the purchaser and which, no doubt, explains why there are so few ledger stones in churches.

Indeed, the ledger stone phenomenon was short-lived, for the Burial Act of 1854 prohibited intramural burial in favour of municipal cemeteries, although there was a caveat in the act that where space was still available in a vault or brick grave constructed prior to the date of the act, it could be used until all of the space had been taken up at which time it would be deemed ‘full’. Generally, then, ledger stones were in use between 1625 and 1854.

TYPES OF LEDGER STONE

Most ledger stones are quite large, measuring 76 by 183cm, although as they were cut in the age of Imperial measurement this can be translated to 30 by 72 inches. Types of stone vary; the most common is black marble, although they were also available in white marble, Purbeck stone and Portland stone and there are also examples in cast iron.

Black marble ledger stones sometimes incorporate other coloured marbles, for example in the form of an inset roundel of white marble at the head end of the stone depicting the armorial bearings of the deceased. Some ledger stones have infilled lettering, usually of white mastic, while others have brass lettering and there are still a few which bear traces of gilding.

While most ledger stones are marble some are freestone (usually a local fine-grained limestone or sandstone), but in the main these were only used as temporary sealing stones. Many survive simply because the family had relocated. Indeed, the majority of such stones were laid following the burial of a child during the early years of a couple’s marriage and while the grave was intended for further use this rarely took place if they had moved to another town. Unfortunately, freestone does not retain inscriptions well and many of the legends have now eroded.

INSCRIPTIONS

Ledger stone inscriptions are usually in English but some, particularly those commemorating the clergy, are in Latin. There are also some Huguenot burials in City of London and Norwich churches whose ledger stones are inscribed in French, but these are very rare.

The standard legend begins ‘Beneath this stone lies…’ or ‘Here lies deposited the remains of…’ . It was standard practice for the font size of the name of the deceased to be larger than that of the rest of the inscription, sometimes in italics, and the usual initials denoting academic honours, such as ‘BA’ or ‘MA’, were frequently used, although the longer forms ‘Bachelor of Arts’ or ‘Master of Arts’ were occasionally used.

Some ledger stones begin with ‘HJ’ or the fuller ‘Hic jacet’, which means ‘Here lies’, although ‘HLD’, for ‘Here lies deposited’ is sometimes seen. The use of initials was, at least in part, a question of economy: the cost of cutting ‘HLD’ would have been far less than for the 17 letters of ‘Here Lies Deposited’ when one was being charged by the letter. Similarly, a Latin translation of an English inscription could land the purchaser with a bigger bill if it made the inscription longer.

Some ledger stones have exceptionally short inscriptions, but this does not mean that the lettering is any more crude than those with a longer legend. Probably the shortest would be the name of the deceased and the year of death, such as:

JOHN SMITH

1801

whereas those which were to be read in association with an adjacent mural monument had simpler markings, such as:

J S

1801

merely to indicate the place of burial. Furthermore, if the mural monument is signed by a sculptor, that may give an indication of the artist also responsible for the lettering on the ledger.

LETTER-CUTTERS AND MASONS

The provision of ledger stones, particularly in the 18th century, was usually limited to letter-cutters working in the larger towns. Much of the black marble used was imported by merchant ships as ballast so letter-cutters’ yards were often based in ports. For example, the Stanton family of letter-cutters had their yard in Holborn, close to the wharfs along the commercial stretch of the River Thames. Similarly, Britain’s extensive system of navigable rivers and canals was used to transport the finished items to their destinations. Indeed the cost of transporting a heavy ledger stone to a remote rural church was almost the same as the cost of the stone itself.

|

||

| Polished ledgers in the Bouchon Chapel, Norwich Cathedral (Photo: Roland Harris) |

The inscriptions usually begin with the name of the prominent male in the grave and it is not unusual to discover from the inscription that he died some years after the death of his wife, which is further evidence of the use of a temporary freestone ledger before the final one was put into position. However, there are examples of black marble slabs which have space left at the top for the primary name, which is an indicator that the husband married again and is buried elsewhere with his second wife. Subsequent inscriptions were usually cut in situ, which explains the use of a different ‘chisel’ or letter-cutter’s hand if the original letter-cutter was no longer in business.

Laying a ledger over a brick grave was a delicate operation for they were bulky and unwieldy items, frequently as much as 15cm (6 inches) thick. Once the temporary stone had been lifted and discarded, three or more wooden bars were placed across the width of the grave and eight men, holding the ends of four lengths of canvas webbing passing beneath the slab, would take the strain as the wooden bars were removed. The slab was then manoeuvred into position.

Subsequent re-openings of a brick grave can often be identified by the chips around the edge of the ledger stone where crow-bars were used to lift it onto wooden rollers for temporary removal.

LOCATION

The location of burial places in the church depended on the role and status of the individual being interred. Consequently, ledger stones over the graves of clergymen are usually to be found in the sanctuary or chancel, although some benefactors were also afforded that position. Prominent members of the community are usually found either in the centre alley of the nave or, if they required a more substantial vault, at the east end of the nave side aisles or at the west end of the church. The spaces in the side alleys of the nave were usually reserved for wealthy bachelors and spinsters. This was merely a general rule and was not necessarily sacrosanct.

It also has to be borne in mind that many churches were re-paved in the 19th century and some architects were not averse to clearing all of the ledger stones into the churchyard. This was the case at Great Massingham, Norfolk when the architect Daniel Penning restored the church there in 1863. Many ledgers were merely transferred to the west end of the building, as at Saffron Walden, Essex in 1859-60 when RC Hussey restored that building. The fashion in the mid-19th century for elevating chancel altars on three steps saw the obliteration of some ledger stones, many of which are now only half visible, and heating programmes also saw the removal and re-siting of ledgers in the way of the heating pipes.

Late 20th-century re-orderings have also been responsible for ledger stone relocations, although perhaps the saddest cases are those where churches have decided to smother their floors with broadloom carpeting, thus obliterating the very presence of the ledger stones and making them almost impossible to record.

CARE

Ledger stones are easy to clean, although water should never be involved. The simplest and most efficient approach is to vacuum them, having first released the years of dust from the cut inscriptions by means of a medium-hard stencil brush. That done, an application of beeswax will seal the stone and, once polished, will bring it up looking as good as it did on the day it was laid. From then on a weekly dust with a dry mop will suffice.

At all times it should be remembered that ledger stones are important items, for not only do they mark the resting place (in the main) of those they commemorate but they also contain valuable genealogical information on the deceased within the brick grave. They should not be used as a convenient hard surface for the stacking of chairs, nor for flower stands, drum kits or sections of staging. Nor, worse still, should they be used as a convenient hard-standing for lavatory pods (as noticed recently in a church in Norfolk).

It is essential, especially in those more rural and isolated churches which do not have efficient heating systems, that they are not covered by carpeting. In cold weather the burial space beneath a ledger stone gives up dew and it is not unusual for the stones to be powdered with dew-drops in the early morning. If a church has laid broadloom carpeting over such stones then this will only lead to rapid decay of the carpet, so it is always prudent to let such stones breathe naturally or, if necessary, to cover them with rush matting.

THE LEDGERSTONE SURVEY

It has been estimated that there are about 250,000 ledger stones in England and Wales. The monumental brasses in the United Kingdom have already been fully recorded and it was in 2002 that the Ledgerstone Survey of England & Wales was established to do the same for ledgers.

NADFAS church recorders now include ledger stones in their church surveys but anyone can take part (see www.lsew.org.uk for more information and to download a copy of the recording form and guidelines). Recording ledger stones will give you hours of pleasant pastime, will help to document a much-neglected form of funerary commemoration and will, I trust, prove that ledger stones are not quite the ‘ugly duckling’ of the monument trade some would claim.

Recommended Reading

R Bigland, Observations on Marriages, Baptisms, and Burials, Richardson & Clark, London, 1754