Let There be Light

Roger Gardner

Funding

support from the Millennium Commission has enabled over 400 churches in

England, Scotland and Wales to realise floodlighting projects for the Millennium.

The Church Floodlighting Trust Ltd was set up to administer the grants,

provide technical support for the churches involved, and ensure that the

floodlighting was of a high standard. This was a unique experience for the

Trust's lighting engineers, who, in collaboration with the Trust's Technical

Panel, have each supervised about 50 installations from conception to completion.

Some of the insights gained from this unprecedented number of designs, realised

over a limited period, are summarised here for the benefit of others who

may be considering floodlighting their church or chapel.

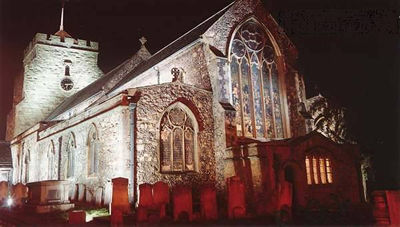

St Mary's, Eastbourne. First floodlit with gas lamps for the 1937 coronation, the current scheme uses metal halide projectors with some in specially designed stone housings. The interior lighting is used to advantage to add interest to the east elevation, which cannot be wholly floodlit |

DESIGN CRITERIA

The following questions need to be considered when discussing design criteria - the issues they raise are common to the floodlighting of all buildings:What are the principal elevations and viewing directions? Which facades cannot be seen and need not be lit?

- Which is the most appropriate light source to employ? (This entails assessing the colour rendering and perceived warmth - the 'colour temperature' - of the lamps available, and the effect of these characteristics on the materials used for the building) Where might floodlights be positioned and where may they not be placed? How much light is needed? (taking into account local ambient light and the reflectivity of the surfaces to be lit)

- Are there architectural rhythms that should be acknowledged? (Relevant floodlight positions can reinforce such elements and increase appreciation of the architecture)

Modelling of the structure and revealing textures of surfaces enhances the visual effect and requires particular positioning and angling of the floodlights.

LIGHT SOURCES

The choice of light source and how much light to use are both crucial for a successful design and need further explanation:

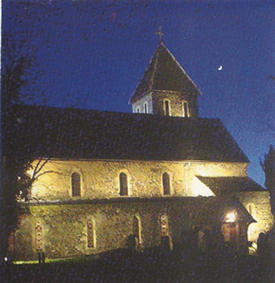

St Mary's, Northolt. A suburban church but situated in a park, illustrating the importance of designing for the correct level of ambient light and the use of good colour rendering lamps |

Light sources can appear

to be warm, neutral or cool. These descriptions are usually applied to lamps

having a colour temperature below 3,200 degrees Kelvin, around 3,500 degrees,

and above 4,000 degrees, respectively. 3,000 degrees is a good target for

a warm effect and 4000 degrees and above may be suitable for a cool or 'moonlit'

effect. Colour rendering is assessed by means of the 'colour rendering index'

which ranges from under 30 (poor) to 100 (excellent) and must be related

to the building's materials and surfaces. A light source may flatter one

material and detract from another's appearance, so it is often advisable

to conduct trials before confirming the most appropriate lamps for a project.

Guidance on how much light to use can be found in a joint CIBSE and ILE

publication Lighting the Environment. The amount of light in the

vicinity effects the quantity of light needed, as does colour, reflectivity

and cleanliness of the building. For example, dirty red brick requires far

more light for effective floodlighting than a clean white surface - sometimes

up to ten times as much, depending on the colour properties of the light

used. Less light is needed for floodlighting in rural areas than in towns,

where there is more ambient light with which to compete. Typically, some

20/30 lux of incident light might be appropriate in a village and more than

100 lux in a city centre.

Running costs are important, involving energy charges and the cost of replacing

lamps. Hence the efficiency of the lamp and any associated control gear

must be considered as well as lamp life when choosing the most appropriate

lamp.

Having considered these general points, what special needs do churches have

and what are some of the pitfalls to avoid? One practical way of answering

these questions is to list some important points that emerged as the Millennium

scheme proceeded.

Davington Church. A little light goes a long way: only eight 35w CDM-R lamps were used for this elevation |

In the Church of England, the permission of the Church (known as a 'Faculty') must be obtained for all alterations including floodlighting, and other denominations might only require local consents. The church architect will be able to advise which authorities to consult. Planning permission is usually needed when column mounted floodlights are two metres above ground and when floodlight housings are higher than one metre, but there is no common approach by local authorities. Some require planning permission to be obtained, others do not, but it is always advisable to notify of an intention to floodlight a building. Conservation areas and listed buildings will involve special restrictions, and in certain smaller denominations the introduction of floodlights may also require listed building consent if the church is a listed building.

Many designers, installers, and manufacturers proposed floodlights that were far to powerful. Frequently, generous numbers of 400w wide angle 'area floodlights' were recommended. Usually power reductions were possible and fewer controlled beam projectors were eventually installed. This gave improved modelling and energy savings, as well as minimising glare and light pollution through better control of spill light. Concealing floodlights by burying often seems an attractive option, but presents some disadvantages:

- spacing between units, and the offset from the wall to be lit, has to be restricted to minimise light 'scalloping' on it. Tilting projectors slightly reduces this effect.

- setting lamps too close to the building produces long shadows from even minor projections which can conceal other features.

- a return at first floor level will not be lit, and supplementary floodlights may be needed to reveal it.

- most flush floodlights are limited in power to control the temperature of the front glass.

Surface mounted designs

are normally more economical in capital and running costs, as fewer and

cheaper surface mounted fittings are usually necessary.

In the Millennium schemes considered by the Trust, the appearance of small

discrete floodlights was not usually a problem. Designers were usually

able to position them inconspicuously using existing trees, shrubs or

even headstones and monuments. Landscaping and additional shrubs were

introduced only when necessary. Floodlights mounted on buildings were

normally hidden behind parapets and in gullies, but if unavoidably exposed,

finished to blend with their surroundings.

Projectors with inappropriate light distributions were frequently specified.

Often this was due to incorrect assessment of the district brightness,

lack of calculations in design, or because the correct power/ light distribution

was not available from a specific manufacturer, a typical example being

wide angle, symmetric beam, trough floodlights lighting a tower or spire.

Narrow, asymmetric beam projectors would be more effective, using less

power, minimising light spill.

The choice of floodlights was often restricted by the lack of appropriate

baffles and spill shields. As independent lighting designers are not confined

to the limitations of one manufacturer's range, they are well placed to

advise on the selection of suitable equipment.

Unsuitable lamp colour rendering and ambience sometimes lead to undue

distortion of appearance. Here the most common mistake was to use high

pressure sodium lamps which were perhaps chosen for their efficiency,

very long life and warm appearance. Many wanted their premises to look

'warm and inviting', but when interpreting

this desire, designers frequently overlooked the all-pervasive yellow tinge

and poor colour rendering of this source. A limited range of high pressure

sodium lamps is available which have better colour rendering but these still

present a very warm appearance. Other lamps can provide a much more natural

effect, such as the CDM type of metal halide lamps, which have excellent

colour rendering properties and are available in either warm or cool colour

temperatures. These were found to compliment nearly all materials encountered.

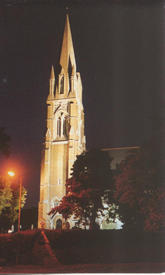

St. Mathew's, Redhill.Narrow beam metal halide projectors lighting

a lofty tower and spire

St. Mathew's, Redhill.Narrow beam metal halide projectors lighting

a lofty tower and spire |

Mixing different light sources or varying colour temperatures in the same

project needs to be approached with care. Ideally only one or two suitable

features should be treated and should always be subject of a trial before

installation.

Vandalism cannot be ruled out in any situation. Accessible floodlights are

best protected with front grilles or enclosing structures such as cages,

even if there has been no trouble in recent years.

Finally, one of the most important points of all: a trial should always

be conducted as it is essential to position and angle floodlights precisely

to get the best possible results. Often only small adjustments are required.

Trials are best done in the early stages of design, but failing this, they

can be carried out immediately prior to installation using the floodlights

intended for the project. They may reveal natural shields such as shrubs,

trees and headstones which help to conceal light sources and screen light

spill, as well as other issues which are not always apparent at the design

stage and require experimentation to resolve. You cannot expect an installer

to position floodlights exactly from a scale drawing: there is no substitute

for positions agreed during a trial and marked accurately on site. A final

aiming and commissioning visit with designer, installer and client on site

is also invaluable for achieving a good design and client satisfaction.

Recommended Reading

- Lighting the Environment: A guide to good urban lighting, The Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers

- ILE Lighting Guide 6: The Outdoor Environment, The Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers

.