Limework at St Cwyfan's Church-in-the-sea

Ned Schärer

|

|

| The ancient church of St Cwyfan, Llangwyfan before limewashing, with the mountains of Snowdonia in the background |

On a quiet area of the west coast of Anglesey, between the villages of Aberffraw and Rhosneigr, a tiny walled island projects from the rocky shore out into the Irish Sea. On it, battered by the elements, stands the ancient church of St Cwyfan. When the tide is high the church and its island churchyard are surrounded by the sea, and even the narrow, boulder-strewn causeway which connects it to the shore is frequently submerged. It is a dramatic setting, and as hostile an environment as any faced by soft lime mortar and limewash in the British Isles.

By the spring of 2005 when the current programme of conservation work was due to commence, the exterior fabric of the building was in a poor state of repair. The walls had been pointed with a hard cement mortar, and the windows replaced with polycarbonate sheet. The programme of works involved repairs to the external envelope of the building, including new leaded glazing, and some internal decoration, although this article will focus on the exterior treatment of the walls. To the architect Adam Voelker and contractors Cadwraeth Schärer Conservation it was clear from the outset that very little in this job would be plain sailing. While the contractors were busy planning how to get 15 tonnes of materials across the causeway between high tides and up the steep stone steps, and all the rubble back to the mainland, other people had different concerns. The specification included removal of the heavy cement pointing, re‑pointing with lime and then limewashing. A small but determined group of local people was unhappy about the limewash, because no one could ever remember the church being white, and they campaigned vigorously against it. Cadw was involved in the funding of the project, and the specification had to remain unchanged – there was no room for compromise.

The work was not finally given the go ahead until July 2006, over 18 months late and well into the short summer working window available on such an exposed site. With hindsight this may well have been for the best; inevitably, problems arose very quickly with the onset of autumn conditions. Had the contract been given a clear run at the height of summer, the problems may not have become apparent so quickly.

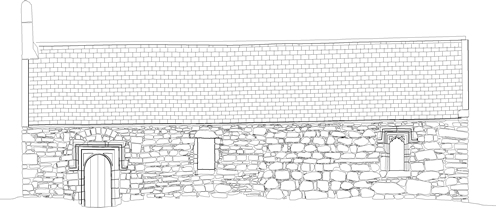

The most exciting part of the project was always going to be the removal of the old cement mortar: as this would provide the archaeologists with a rare opportunity to do a detailed survey of stonework that had not been properly visible for hundreds of years. The old pointing was removed in early August, very carefully, using only hand tools. This sounds straightforward, but the truth was that the weather made every process difficult. The raking out was hard on the wrists, but the dust blown out of the joints by the sea breeze resulted in constantly irritated eyes. Safety glasses protected the stonemasons from bits flying off, but not from the swirling dust – swimming goggles worked, but vanity dictated that the masons only wore them at high tide when there were no visitors. When the raking out was finished the contractors left the site for a couple of weeks to allow Gwynedd Archaeological Trust to do its work.

|

|

||

| Above left: the arcade begins to re-appear. Above right: the north wall as the hard cement is removed | |||

THE EVIDENCE UNCOVERED

It is unclear why the church is where it is; it is certainly not the most convenient of locations – a new church was built for the parish in 1872 a little way inland. There are dozens of ancient churches and religious sites on Anglesey, and this site, despite the presence of a noisy race track on the adjacent headland, and the proximity of two RAF bases, must retain as much of a spiritual atmosphere as any. Those of us working on the job, especially when we camped there because of the tides, and visitors who came across the causeway, almost always commented on the very special feel of the place.

Aberffraw, a mile to the south east of St Cwyfan’s was once a maerdref or manor house belonging to the kings of Gwynedd, and the building may have received some kind of royal patronage. During the 12th century and again during the 15th century, after the havoc dealt by the Black Death in the middle of the 14th century, Gwynedd was relatively stable and prosperous. These periods coincide with significant archaeological findings.

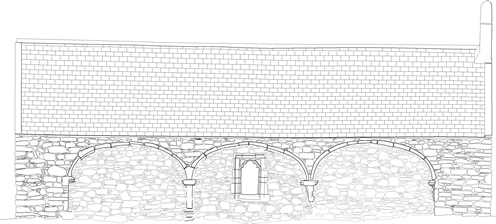

There are two types of stone used in the building: sandstone grit thought to be from the Bodorgan Paradwys area on the north side of the Malltraeth estuary, about four miles from the site; and schist, a metamorphic crystalline rock which exhibits a layered structure and is found plentifully on the shoreline at Llangwyfan. The archaeologists believe that the evidence points to the earliest stone church on the site being built in the 12th century using the sandstone. There is a clearly defined projecting string course of very weathered moulded sandstone half way up the wall on either side of the door, to just beyond the first window. There is a similar feature in remaining 12th century masonry at Aberffraw church. It has long been known that the present door arch, although very old, had been fitted into a larger and older arch, and when the old pointing was stripped away it was possible to see the earlier doorway with its distinctive semi-circular arched head – which is possibly 12th century. It was also possible to see clearly that the lower courses of the west gable, and the westerly half of the south wall, were constructed with small neatly cut sandstones; and it was easier to see the string course. (This is shown in the archaeologist’s drawings below).

|

|

| Gwynedd Archaeological Trust's records of the north wall (top) and the south wall (bottom) |

During the later part of the 14th century it is thought that the church was repaired or extended to its present length using large and irregular pieces of local schist, while some of the squared sandstone from the original building was incorporated into the quoins. By the end of the 15th century the church had changed yet again, with the addition of a second aisle on the north side linked to the original church by an arcade of three arches. This second aisle was demolished sometime between 1802 and 1846, presumably after an unsuccessful struggle against the sea and the elements. The shape of the three sandstone arcade arches was always visible from inside the church, but had been hidden in modern times by the outside mortar.

REPAIR WORK

Once the archaeologists had finished, the contractors were able to complete the next stages of the job: minor repairs to the roof and the re-pointing. The specification for the pointing was 1 part naturally hydraulic lime (NHL) of strength class 3.5, to 2–2.5 parts sharp, well-graded sand (3-4mm grit) from Cefn Grainog quarry south of Caernarfon. Shells from the beach were washed to remove the salt and added to the mix to match the original mortar. Visual analysis and a quick dissolution test suggested that the original mortar was very lime rich and that the sand looked identical to that found on the beach. We do not know whether the water in the original mix was fresh or straight out of the sea.

The decision was taken early on that the work would be as low-tech as possible, mixing the mortar by hand using a larry and shovel in a plasterer’s trough on the island. The mix was well worked and left to fatten up for a few hours; it was then knocked up again into a stiff mortar which would be easy to work and compress into the joints.

After doing small masonry repairs and dubbing out a few areas, the mortar was finished flush to the stonework and then worked into the edges of the stone with hessian or a stiff brush when it was slightly soft, to get a good bond and to weatherproof joints with efficient run-off for the rain and sea-spray. Once the mortar had firmed up enough, it was beaten with a churn brush and the aggregate brought to the surface by scraping back with a trowel and leaf (a small pointing tool). It was then kept damp for a week under hessian sheets. The weather was difficult to deal with especially when the protecting hessian blew away. The masons had to work quickly and cover the mortar immediately from the drying wind and sun. Fortunately, it was possible to staple-gun the hessian to the wall plate – without which the wind would have caused a real problem.

As the intention was to limewash the walls afterwards, it was decided to experiment with three different types of hydraulic lime, St Astier, Castle and Singleton Birch, partly to test their workability, and perhaps also their longevity. All three worked well, but the British lime, Singleton Birch, was the nicest to use in these conditions because it stayed workable for longer and made a slightly fattier mortar.

The re-pointing had gone to plan and even transporting the materials to and from the beach across the causeway did not present too much of a problem – everything from a horse and cart to a helicopter had been considered, but in the end a dumper truck solved the problem. By now it was mid-September and the weather was worsening. With some apprehension an attempt was made to limewash the north, east and south walls, only to find that with a day or so of heavy rain, most of the limewash, particularly on the exposed south wall, was washing off.

It was clear that a re-think was necessary and after talking to the vicar Canon Madalaine Brady and Adam Voelcker the architect, it was decided to do some trials over the winter to see what would work best. At this stage the two most sheltered sides, the north wall and the east gable wall were reasonably well covered with limewash. The long south wall was very patchy; at that stage no attempt to limewash the west gable wall had been made.

At that time the problems with the limewash were very disheartening, but a year later I can say that the learning experience and experimental tests proved to be of great interest and will, I hope, help others in similar circumstances. The problem was twofold – the difficulty of limewashing large expanses of wall with full exposure to the ever-changing weather, and the non-porous schist. The wind proved to be the hardest of the elements to deal with: windbreaks were tried, but they blew down as the wind changed direction so often; hessian sheets stayed in place, but they flapped against the fresh limewash and rubbed it off. As for the stone, the schist, a non-porous metamorphic rock simply would not take the limewash: it was as if it had been sprayed with a water-repellent.

To find the best constituents, trials were carried out on the south wall over the winter. These included a shelter coat mixed in an ordinary fat (non-hydraulic) lime and one with a binder of casein, a shelter coat mixed in a feebly hydraulic lime, and a straight hydraulic limewash. Each sample patch had five coats. After six months of winter and spring weather, the shelter coat mixed in a feebly hydraulic lime was the most successful, and all the trials had worked better than the straight non-hydraulic limewash.

In the summer of 2007 the team set to and re-limewashed the whole church. The south wall was brushed back with a stiff brush and all the weakly bonded previous limewash removed. Five coats of the shelter-coat were applied, consisting of one part Singleton Birch NHL2 to two parts fine sand. One stroke of luck was that the shelter coat dried a very similar colour to the Ynys Mon pigment – a naturally occurring material from Parys Mountain near Amlwch which had been in the specification.

The benefit of using a hydraulic lime was that it went off more quickly and therefore could cope with the weather sooner. With the slight set of the hydraulic lime the hessian protection did not cause as much abrasive damage, and we were able to damp down the surface sooner on dry and windy days. A week was allowed between each coat so the limewash could fully carbonate. After each application the craftsman went over the surface with a dry stock brush to remove any loose material, then wetted down the wall and repeated the process.

The shelter coat was almost a slurry in consistency and had to be applied with the brush from a plastic dust pan and brush set, because the sand clogged normal brushes. The speed with which it could be applied in this way meant that there was extra time to look after the fresh walls and keep them damped down. Another added attraction of this method is that it is closer to the old-fashioned local method of using a long-handled broom to apply limewash. I shall try it again in the future, or possibly even flick the shelter coat on, as in the manner of harling or rough cast.

|

|

|

|

| Top: the south and west wall with its bright new limewash seen from the churchyard. Above left: the south side in January 2007 showing the Norman arch over the entrance. Above right: the south and east walls seen from the shore | |

Work on the exterior eventually finished in the summer of 2007, and at the time of publishing this article the church looks complete, with the soft whiteness of the limewash constantly changing, lightening and darkening as first one wall and then the next is lit by the sun, or wetted by rain or sea spray.

There have been times over the past year or so when I wondered if we were taking the best course of action for the building in the long term. Of course removing the cement was essential, but I wondered if it might have been better to have either left the masonry and new pointing bare without a shelter coat, or to have gone further than we did and fully harl the building. In the end I think we got it right: we have protected the building from the elements and the sea spray but at the same time the archaeology can still be read.

However, for all this work to have been worthwhile, the shelter coat, particularly on the two most exposed walls must be re-applied regularly. Over time, if it is done properly, the layers will build up like a shell and it should be possible for the intervals between applications to become longer. The building would be in an even better state if funding could be found before too long to remove the cement patches and areas of emulsion paint from the inside walls, and replace them with lime mortar and limewash.