The Lost Gardens of Barnsley

Wentworth Castle Gardens and Stainborough Park

Erika Diaz Petersen, Hilary Taylor and Stephen Elliott

The Wentworth Castle and Stainborough Park estate lies to the west of Barnsley, in the heart of a landscape transformed by coal mining, yet remarkably it retains significant aspects of the character of early phases of its development. The Grade I-registered gardens and historic estate are now in the care of the Wentworth Castle and Stainborough Park Heritage Trust and are open to the public, and the Grade I-listed house, Wentworth Castle, is now a college for continuing education.

|

|

| The house from the south with its Palladian front and, below, a plan of its restored grounds |

Growth and decline

The most significant

transformation of Stainborough Park took place in the 18th century

following the purchase by Thomas Wentworth (1672-1739) of the

estate and its manor house from the Cutler family in 1708. Thomas

was a man of wealth, influence and success, who had been thwarted

in an expectation of inheriting the Strafford earldom and the

neighbouring estate of Wentworth Woodhouse. His choice of location

was certainly fuelled by what had become a bitter rivalry. As

it happened, his nephew, who had inherited the title, died young,

and Thomas was ennobled as the 1st Earl of Strafford in 1711.

It was at this point that Thomas began to develop a grand estate

befitting his title. He subsumed the Cutler house within a grand

Baroque edifice and surrounded it with elaborate gardens, monuments,

pools and fountains.

Thomas's son William (1722-1791) inherited the estate in 1739 and continued in the spirit of competition with his cousins at Wentworth Woodhouse. He constructed a new wing in the Palladian style and enhanced the gardens and park with further monuments, more 'naturalistic' planting, and an early serpentine lake to create the illusion of a picturesque river when viewed from the house.

In 1802 the estate was inherited by Frederick William Thomas Vernon (1795-1885), who assumed the name of Vernon-Wentworth. Assisted by the sale of mining rights beneath the estate, the Vernon-Wentworths further embellished the 18th-century landscape, which already represented an unusual survival of early 18th-century tastes in formal gardens. Their most significant contributions in the 19th and early 20th centuries included a conservatory (featured on the first series of the BBC's Restoration), extensive rhododendron planting, and vineries, now lost, as well as other features of the walled gardens.

Following the Second World War, the house, gardens and part of the estate were sold to the Barnsley Education Committee. While the custodianship of the local education authority and council in many respects helped to preserve aspects of the estate, a number of subsequent developments have had a significant impact on the landscape. These have included new buildings and a car park near the house, a sewage treatment plant, tennis courts, a football pitch, and open-cast mining. Much of the surviving 18th-century parkland was lost to farming.

Although efforts were made in the latter part of the 20th century to recover aspects of the gardens, they continued to become overgrown and increasingly shaded by a predominantly evergreen canopy and the vigorous growth of the extensive rhododendron collection. As on many historic estates, the pressures of time and lack of resources led to an inevitable deterioration, despite the considerable effort invested by the people who have worked on and cared for the site, and by the end of the 20th century, several buildings and monuments were on the verge of being lost.

Halting the decline

A partnership was formed between the Northern College and the Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council to further restoration plans for the estate, and in 2002 the Wentworth Castle and Stainborough Park Heritage Trust was formed. Ownership of the main buildings and gardens was transferred to the trust, and in 2004 the Vernon-Wentworth family donated the wider historic landscape as well. During this time, a very successful campaign for funding was initiated to halt the decline and to begin a programme of restoration.

|

The first phase of a challenging site-wide restoration project is now drawing near to completion. The works, with a budget of approximately £15.5 million, have included buildings, landscape and parkland restoration, new college and visitor facilities housed within the Home Farm, two new car parks and a new entrance garden. Funding to support the project has been received from the Heritage Lottery Fund, Yorkshire Forward, English Heritage, the European Union, Natural England, Defra, South Yorkshire Forest, Waste Recycling Environmental Limited (under the Landfill Tax Credit Scheme), the Learning and Skills Council, and others.

The design team included Purcell Miller Tritton as lead design and conservation architects, Hilary Taylor Landscape Associates Ltd as historic landscape consultants, Arup as engineers, Buro Four as project managers, and Rex Proctor & Partners as quantity surveyors and planning supervisors.

Principal contractors were Quarmby Construction Company Ltd (Home Farm and Wentworth Castle), William Anelay Ltd (monuments), P Casey (Land Reclamation) Ltd (access and landscape works), Lotus Construction Ltd (kitchen courtyard and coach house), Practicality Brown (South Avenue planting), and Lowther Forestry (tree works, woodland planting and parkland fencing).

PARK BUILDINGS AND MONUMENTS

There are 26 listed buildings within the grade I-registered landscape. The recently completed monuments project concentrated on the seven monuments in the most perilous state of decay, five of which were on the English Heritage Buildings at Risk Register.

Within the project's main aim of making the monuments safe and accessible to the public, the strategy was to conserve the existing historic features and, where appropriate, reinstate features that represented, contributed to and enhanced the significance and values associated with each period of development. Repairs were designed to respect the quality of materials, performance, techniques and craftsmanship of the original fabric.

Over and above the normal technical challenges that arise out of a project of this nature, the special challenges of the project can perhaps be summarised under four headings: geographical, logistical, ecological and archaeological.

Geographically, the monuments are scattered over 268 hectares of parkland. The Rotunda restoration required the construction of a 500m-long temporary access road, while the Duke of Argyll Monument was only accessible over fields with a tractor and trailer.

Logistically, it had been decided to subdivide the wider £15m restoration project down into smaller and more manageable staggered contracts so as not to overwhelm the design team or one single contractor. It was therefore deemed essential to have the full-time site presence of a resident site architect/co-ordinator.

Ecological constraints were placed on the project by the presence of great crested newts, bats and, to a lesser extent, badgers. This necessitated pre-contract surveys to identify the scale of mitigation necessary prior to licence applications being submitted to Defra.

Newt mitigation consisted of hand searches to remove the creatures from worksites and the erection of special fencing around each monument to stop them returning while work was in progress. Bat mitigation measures resulted in an embargo on pointing work during the August to November mating season.

Lastly, several monuments required archaeological surveys and watching briefs, including Stainborough Castle in particular, as its hilltop location was reputed to have been an iron-age settlement.

|

|

| The two remaining drum towers. The plastered wall shows that this was once its interior. |

Stainborough

Castle

The sham medieval

castle comprising gatehouse-keep and curtain wall with four square

towers (one for each of Thomas Wentworth's children) was built

on the highest point of the estate. It is listed Grade II* and

was constructed between 1727 and 1730.

The gatehouse was not well founded and had to be rebuilt in 1765 by William Wentworth. Nevertheless, from 1956 to 1980 two of the drum towers and great hall gradually collapsed leaving only two drum towers and the entrance vault standing. Subsequent rain penetration into the top of the entrance vault had flushed the mortar from the joints, and the single stone stair, constructed from stone treads bearing into tapering slots in the stone newel, had weathered beyond repair, rendering the whole structure unsafe for public access.

The conservation approach adopted was not only to safely consolidate the structure as a ruin in terms of stone indenting, lime-mortar pointing, rough-racking of exposed wall heads, and the installation of wrought-iron grilles and railings, but also to open up the structure to the public and interpret the ruin.

The entrance vault was consolidated in-situ by inserting temporary propping and installing a mesh-reinforced concrete crust over the top following the shape of the vault. A level reinforced concrete slab was then cast above this, creating a viewing deck in the position of the great hall. The original internal walls, now exposed to the outside, were lime rendered, integrating fragments of original decorative plaster, to make it clear that they were once internal walls.

A new galvanised steel spiral stair with top viewing platform has been installed in one of the full-height towers to reinstate the outward views once enjoyed by the Wentworth family.

|

|

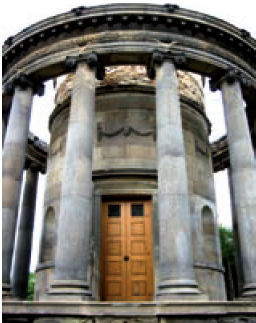

| When the Rotunda lost its roof in a fire, its colonnade became unstable. It has now been tied back with stainless steel ties. |

The

Rotunda

The Grade

II* Rotunda, was probably built by William Wentworth between 1742

and 1746. The design is very similar to the Temple of Sybil at

Tivoli, near Rome, which William may have seen whilst on a 'grand

tour' of Europe after the death of his father. It comprises a

central stone drum over a basement vault with an encircling colonnade

and entablature. A crown fire in the closely surrounding trees

in the 1980s led to the loss of the timber and lead roof. (In

a crown fire, which is the most dangerous and destructive class

of woodland fire, flames rise up the trees and across their crowns.)

This has had a catastrophic effect on the structure. The outer

colonnade was no longer tied to the inner drum and with rain penetration

into the wall heads and basement vault, the colonnade has moved

outwards, the entablature joints have substantially opened, and

the expansion of iron cramps has resulted in spalling of the carved

detail.

As funding was not available to take down and rebuild the colonnade, nor to reinstate the roof, radial stainless-steel rods were installed to tie the colonnade to the drum, and the wide open joints of the entablature were pieced in with stone, but omitting the carved detail to distinguish these as a joint filling. Iron cramps were cut out and replaced with stainless steel, and the spalled stone was made good with modelled plastic stone repairs. The wall heads were capped with lead and the floor over the basement vault was waterproofed, with substructure drainage installed under the colonnade walkway. Finally the monument was cleaned with three per cent hydrofluoric acid to remove the heavy sulphate deposits.

The

Strafford Gate

Perhaps one

of the most controversial proposals of the project was the relocation

of the 1768, Grade II, Strafford Gate, which was erected by William

Wentworth over one of the principal entrances to the estate.

|

|

| Strafford Gate in its new position adjacent to the Menagerie House |

The problem was that the location of the proposed car park (which is discussed below) required the use of this entrance to the park, but visitor coaches would be too large to pass safely through the arch. After carefully considering all the options, it was concluded that the best solution was to move the gate 20 metres into the park on the same axis. This would preserve the tunnel effect of the approach along a tight holly-lined lane and maintain its 'group value' with the neighbouring Menagerie House. Fortunately English Heritage agreed and listed building consent for the move was granted. To assist visitor interpretation the original footprint position of the gate was delineated in stone setts.

The

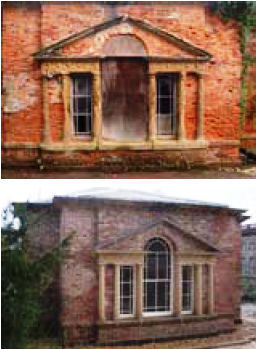

Gun Room

The garden

pavilion, known as the Gun Room because of its Victorian usage,

was originally built in 1732 as a banqueting house or bath house.

It has fine internal decorative plasterwork, and is listed Grade

II*. Over the years the brick and stonework of its western facade

had eroded dramatically as a result of a simple flaw in the original

design which caused the eaves to drip. Soluble sulphate deposits,

salt crystallisation and frost action and the accumulation of

water at the base of the building did the rest.

|

|

| The badly spalled brickwork and external envelope of the Gun Room has now been restored, safeguarding its magnificent interior for future restoration. |

With the monies available the defects of the external envelope were tackled, thus safeguarding the interior for future restoration. The eroded stonework was replaced with new Blaxter sandstone, the spalled bricks were cut out and replaced with matching bricks from stocks held on site, and cement-mortar pointing was replaced with lime mortar. To assist drainage and drying out a field drain was laid in a gravel-filled trench around the perimeter.

Other monuments

Stone cleaning

was also carried out to the marble statue of Thomas Wentworth,

the first Earl of Strafford (1744), the Duke of Argyll Monument

(1744) and the Corinthian Temple (1766). Following cleaning trials,

the Thomas Wentworth statue, by Flemish-born sculptor

J M Rysbrack, was cleaned by Cliveden Conservation using a mild

detergent (five per cent Synperonic solution in de-ionised water)

and an ammonium carbonate poultice to break down the heavy sulphate

deposits. The others, both of sandstone, were cleaned to remove

sulphate deposits using three per cent hydrofluoric acid.

LANDSCAPE RESTORATION

Wentworth, like other historic landscapes, is a complex site with varied significances. These include the multiple phases of its historical development and its environmental, economic and social importance. While Wentworth has been home to the Northern College for many years, the opening of the gardens and parkland to the public introduced both the need to accommodate increased access for people arriving at the site, and the need to make it as accessible as possible for all to enjoy.

The gardens

The philosophy

governing restoration within the gardens has been to rejuvenate

and restore the most significant surviving features from each

phase of the gardens' development, to provide year-round interest

for visitors to the gardens, and to make as many parts of this

very steep landscape accessible to as many people as possible.

Planting in each of the areas has been carefully chosen to be

appropriate to the relevant period.

|

|

| Rysbrack's monument to Thomas Wentworth before and after cleaning and consolidation |

The gardens contain many significant 18th- and 19th-century plants, as well as being home to a variety of protected fauna, including badgers and nesting birds. These sensitivities have particularly influenced the timing and method of working, and ground-intrusive works have also been restricted where archaeological sensitivities are thought to exist.

Works within the gardens have been planned with great care, and limitations have been placed on the size of machinery that may be used during construction works, which have included substantial tree works, the creation of a new entrance garden, and the re-surfacing and creation of a network of footpaths. The paths have been surfaced primarily with an inert self-binding gravel, and fibre-reinforced turf.

The most significant early 18th-century component of the

|

|

| The Corinthian Temple overlooking the south lawn |

gardens is popularly referred to as the 'Union Jack' garden, a rare survival of the type of wilderness garden popular in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. A large sweet chestnut, for which records survive of its planting in the early 18th century, and several yew hedging plants remain from the creation of this garden. However, the yews and several hollies had grown into trees and they have now been reduced in size, and the hedges replanted. An attempt has not been made to restore the planting in this area to its original composition, which included 'shredded' young oaks, maintained with only a tuft of leaves at the top, but instead to provide a garden full of colour and scent within the structure of the original 18th-century garden.

The 19th-century influence on the site is still represented by the extensive rhododendron collection, which has been surveyed

|

|

| View west along the central walk of the southern part of the restored 'Union Jack' Garden, including a semi-mature sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa), planted to mirror the surviving 18th century tree (Photo: IJM Photography) |

and catalogued; an azalea garden; a flower garden (which at various times has contained roses and bedding schemes); and the now derelict conservatory, which is to be restored in the next phase of the project.

The gardens not only represent a remarkable survival of 18th-century landscape design, but are also home to three National Collections of plants: Camellia x williamsii, Rhododendron species, and Magnolia species. The gardens team at Wentworth has undertaken an ambitious programme of reorganising these collections, propagating and transplanting many of the specimens.

The ha-ha wall south of the gardens, constructed in the early 18th century, was one of the earliest features of its type in the country. Now in a very poor condition, it was substantially restored using sandstone from the estate. A new entrance to the gardens was also provided to manage the new influx of

|

|

| The

Duke of Argyll Monument after cleaning and, below, a detail

showing the sulphate deposition on the sandstone that was

removed

|

|

|

visitors passing through the new garden to the east of the house, and a new dry-stone bridge was constructed across the ha-ha, also with site-won sandstone. Its location was carefully chosen to provide an inviting point of arrival into the gardens, and to reveal new views of the house and park.

The park

Stainborough Park is still very much a working estate, with four farmers tenanting land within the grade I-registered park. Two of the farmers have entered into Higher Level Stewardship Schemes this year, reverting arable land to pasture, and herds of deer will be reintroduced.

More than 26 hectares were planted with new trees, restoring the two major historic woodlands on the estate, which were primarily lost in the second half of the 20th century. A principal challenge in restoring the woodlands was the improvement of ground conditions where these had been damaged by opencast mining; 2,535 tonnes of treated composted sewage sludge (TCSS) was employed to help restore the quality of the soil.

Perhaps one of the most ambitious tasks undertaken was to reinstate the early 18th century South Avenue by transplanting more than 50 semi-mature oak trees from elsewhere in the parkland, supplemented by 57 new trees. A large tree spade was employed to lift and move the transplanted trees, which will be carefully monitored to provide them with the best possible chance of success.

Car

parking

Prior to the

first phase of restoration, the only car park on the site was

located immediately in front of the Baroque wing of Wentworth

Castle. It intruded upon views between the house and parkland,

and was not large enough to accommodate the current, let alone

future requirements. A key restoration priority was to reinstate

this area to parkland, and relocate the car park to a less sensitive

location where greater capacity could be accommodated. An early

proposal was for car parking to be located in the historic walled

garden. However, this location was ultimately felt to be too sensitive,

and represented too great a resource for future restoration work

to be used in this way.

Two separate car parks for the college and visitors were ubsequently developed away from key views, following extensive consultation with the local planning authority and English Heritage. The new college car park was sited to take advantage of a natural dip in a field to the north of the castle and gardens, providing direct access to college buildings and space for approximately 150 cars. It will be further screened by a holly hedge and the restoration of a cruciform avenue of trees.

|

|

| Transplanted oaks (descended from original Quercus petraea) along the restored South Avenue (Photo: IJM Photography) |

A relatively poor, early 20th-century wood was identified as the preferred location for the visitor car park. The choice of this site involved particularly detailed consultation, given the requirement for tree felling, issues of parking under trees, and the provision of access. A lack of visibility on the road to the north of the estate meant that it was not possible to create a new junction here, and the only other option was via the Strafford Gate. This option provided the safest solution, although at a cost, as described above.

Removal of the former car park was completed in May 2007. It overlay the site of the early 18th-century octagon-shaped pool and fountain, so its removal was covered by an archaeological watching brief and followed by an investigative archaeological excavation to attempt to locate any remains of the pool.

As of May 2007, much of the grounds has been opened to the public for the first time, and the future of this unique resource as a complete entity is largely assured. Phase II of the restoration project is due to start in 2008, with the first urgent priority being to restore the magnificent conservatory, which is only standing at all thanks to an emergency temporary scaffold. Funding is still being raised for this equally important second phase.