Limewash and Distempers

Elizabeth Hirst

|

|

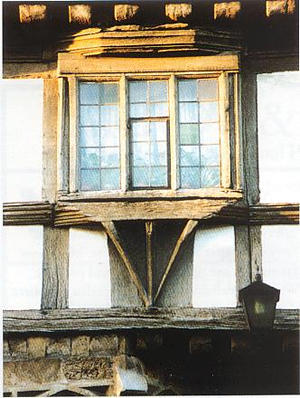

| Ochre limewash on the infill panels of the timber framed pub at Naunton in the Cotswolds, which is owned by the National Trust |

For many years the use of traditional lime-based paints was restricted to those involved in the conservation industry, but more recently these paints have enjoyed a renaissance with the consumer due to increased publicity in interior design and home magazines. Their textured, matt finish and distinctive pastel colours provide an interesting alternative to modern paints, and they are particularly in keeping with the character of old and vernacular buildings.

These paints have much more to commend them than their appearance, as their unique properties make them suitable for various remedial solutions. In particular, their high porosity and permeability enables walls to breathe, reducing the risk of damp.

Externally, limewashes were the most common choice for the walls of buildings particularly in rural areas and small towns prior to the development of modern paint systems. Lead paints were mostly used on joinery and metalwork but are also found on exterior walls of the 18th and 19th centuries.

Internally, limewashes and distempers were used to decorate the walls of most ordinary houses and all but the principal spaces of the most important houses. Even fine wall paintings and decorative schemes found in 17th century interiors such as the Merchant's House in Marlborough (see illustration) were commonly executed in lime-based paints.

LIMEWASH

The basic material of limewash, lime, is derived from limestone or chalk (both are forms of calcium carbonate) which is 'burnt' in a kiln to form quick lime (calcium oxide). This highly reactive material is then 'slaked' by adding water, a process which produces a great deal of heat, causing the water to boil violently. The resulting material (calcium hydroxide) is known rather confusingly as 'slaked lime', 'hydrated lime' and 'non-hydraulic: lime', or even simply as 'lime'. In the wet form in which it is usually kept it is also know as 'lime putty'. To make limewash this material is then further diluted with water to form a thin paint of brushable consistency.

Slaked lime is the principal active ingredient of both limewashes and mortars. It hardens as it dries out by reacting with carbon dioxide in the air, slowly reverting to the stone form of lime, calcium carbonate. Additional binders are frequently added to limewash for a number of reasons, for example to provide greater adhesion and binding of the paint layer, more flexibility, and variations in porosity.

Different quarry sources provide different qualities of lime; high calcium (pure lime) is usually preferred for its consistency of material and its white colour. Other limes may contain impurities and be inconsistent, but can also be used to produce lime paints and may be white or off-white in colour.

As slaking quick lime is a hazardous operation, current awareness of health and safety issues means that this process is less frequently specified by architects. Most now favour the use of the ready mixed product which is available through specialist suppliers.

The

two types of limewash most frequently specified are tallow and casein.

|

|

| The George, Norton St Philip, Wiltshire, showing unpigmented limewash on the exterior walls. |

Tallow limewash

Tallow is a type of animal fat. It is incorporated during the slaking process as the heat which is produced melts the fat enabling it to be evenly dispersed throughout the product.

It can be used on either interior or exterior surfaces, but it is more popular for exterior use as it is slightly less porous than other forms of limewash and can prevent excessive water penetration. It also tends to brush off on clothes, making it less popular for interior use than some other types of limewash, such as casein.

Other oils and waxes can be incorporated as an alternative to tallow. Linseed oil is a popular alternative as it provides durability, some flexibility and better adhesion to some substrates.

Casein limewash

Casein is essentially the solid component of milk. Traditionally it was precipitated from skimmed milk by adding a weak acid. The material reacts with the lime to form a calcium caseinate, improving the binding capacity of the limewash. It can be applied to the inside and outside of buildings but is particularly popular for interior use as it adheres better and is more porous than a pure calcium carbonate paint layer.

In its wet form casein limewash is particularly susceptible to mould formation so a biocide should be added if the mixed product is to be stored for long.

Other variations

Hydraulic limewash may be desirable where setting and hardening is required in wet conditions, as it sets by chemical reaction with water. This product can be made with or without additives by mixing hydraulic lime powder and water. (This product should not be confused with hydrated lime, which is a dry powdered form of calcium hydroxide.)

Modified limewash may incorporate a variety of one or more additives such as oil, resin, wax, polyvinyl acetate or cellulose.

Limewash is compatible with a wide range of building surfaces, including brick, plaster and stonework. It was used historically as a readily available, easy to use and cheap product, making it popular for outbuildings as well as for domestic use. Its slight antiseptic properties also made it desirable as it prevented mould and discouraged insects and vermin.

Limewash's tolerance of damp substrates or newly carbonating plaster was also recognised. Its use is still favoured on damp walls because it has a vapour permeability of at least ten times that of modern resin paint. This allows a faster evacuation of moisture and can minimise the deterioration of the surface and substrate which can be caused by trapping of moisture.

Limewash is used in the conservation of historic building fabric for all the reasons mentioned above and, depending on its formulation, can be used as a consolidating and sacrificial material on crumbling limestone. To simulate the appearance of stone the lime-based coating is frequently tinted with finely crushed stone.

|

|

| The George, Norton St Philip, Wiltshire: detail of wall painting, probably executed in soft distemper |

Application

The surface should be brushed or washed down to remove any loose particles and sprayed or brushed with water to reduce suction. Old limewash or lime plaster will need more damping down that less porous surfaces such as stonework.

The paint is usually applied thinly by brush although airless sprays can be used. It is sem-transparent when first applied and then dries to form an opaque coating. Problems are frequently encountered when decorators try to brush on a visible, thicker layer, as this is likely to craze and crack on drying. It is important that the material is thoroughly brushed out and worked to a wet edge, as limewash abutting a dry edge will become more apparent on drying. Each coat is affected by the suction of the underlying layer and each subsequent layer tends to become lighter on drying; an effect which is particularly noticeable with pigmented limewashes.

Smooth surfaces such as polished limeplaster or gypsum may require a bespoke primer to provide a key for the paint, which can be susceptible to failure through lack of adhesion in these conditions.

DISTEMPER

Glue bound distemper, or 'soft' distemper as it is sometimes called, is one of the most porous forms of distemper paint. It is usually produced from powdered chalk (calcium carbonate) and size (gelatin) such as rabbit skin glue. According to Ian Bristow (see recommended reading), alternatives to chalk have included lime (calcium hydroxide), white lead (lead carbonate) and satin white (made by adding alum or aluminium sulphate to slaked lime). Synthetic glues such as polyvinyl acetate and polyvinyl alcohol can be used instead of animal glue.

This material was often specified to provide a temporary decorative scheme on new lime plaster which is still carbonating, because of its vapour permeability. However, it is inappropriate for walls which have continual damp problems, as eventually the glue binder will become depleted.

Distemper is generally used on sound plaster, wallpaper or previously painted inside surfaces. It is easily marked and discoloured, and it cannot be washed down, which makes its use favoured for ceilings or on wallpaper, but not in children's rooms! It can provide subtle tints and enhances the walls of many fine drawing rooms.

Oil bound distemper

The addition of oil with an emulsifier such as borax (sodium borate) created a more durable and often washable distemper depending on its formulation, which can be considered a predecessor of modern resin based emulsions. It became popular as an interior paint in the early 19th century when a number of manufacturers began to produce it commercially, and it remained in common use until after the Second World War when it was finally superseded by vinyl and acrylic emulsion paints. It is now popular once again for its visual qualities.

Although less porous than limewash, oil bound distemper retains excellent porosity, and it is suitable for a variety of interior surfaces including timber. This material may be known by different names depending on its ingredients: modified limewash, water paint or, if it contains casein, milk paint. The additives are generally the same as those used in limewash. Traditional recipes that utilise casein have included lime (alkali) to dissolve the casein. (Water is lost in drying and the casein hardens to its insoluble form.) Other variations include the use of alkali silicates to emulsify oil, and plasticisers such as glycerine may be added. In recent years other products such as anti?foaming agents have sometimes been incorporated. Traditional recipes are interesting but the reasons for the incorporation of some additives is not always clear; some recipes may have been regionally produced and passed from generation to generation without being questioned.

It should be remembered that limewashes and distempers, with the exception of glue bound distemper, are generally insoluble when dry.

Application

Glue bound distemper is mixed with water and left overnight to allow for gelling. It should be used on a clean, dry surface and previously soft distempered surfaces must be thoroughly removed by washing down with warm water. Uneven or high suction surfaces may be given a coat of claircolle (or clear coat), which is a size coating with some water or pigment added.

Distemper should not be watered down prior to painting as it needs to be applied in its gelled state. It is usually applied by six-inch brush in vertical strips, cutting in the leading edge, the corners, top and bottom edges. It should be flowed on in one direction, finishing top to bottom in one stroke. The leading edge should be kept open and an entire flank or surface finished without stopping or allowing a dry edge. Never brush out or cross the dry work.

PIGMENTS

For both limewashes and distempers, pigments or colouring material may be incorporated from animal, vegetable or mineral sources, provided that they are alkali resistant. Lamp black and natural earth pigments were commonly used in the past as they were cheap and readily available. These included a wide variety of ochres such as sienna, burnt sienna, umbers and yellow ochre. Blue limewash rarely appears until the Victorian period, following the introduction of the first alkali resistant blue pigment, French ultramarine, in the 1830s. Nevertheless, pigments which were not alkali-resistant such as Prussian blue and indigo were also sometimes used in external limewashes which, in any case, have to be renewed regularly.

MODERN TECHNOLOGY?

Weakly bound modern matt emulsions are frequently labelled with 'period' names to entice many to decorate and recreate a fashionable 'traditional' interior. In effect they are frequently using matt alkyd resin based paint with reduced vapour permeability and a restricted palette of colours. Unfortunately, many a proud owner may be disappointed with this alternative material, which fails to mimic the subtle texture and effect for which they were aiming.

Where the external walls of historic buildings can only be painted from scaffolding it makes sense to consider modern alternatives that will last longer than limewash. Silicate paint systems such as Keim provide an alternative as, like limewash, they also allow the structure to breathe and are alkali resistant, but last for decades.