The Ceiling Paintings of St Mary Magdalene

Polly Westlake

|

||

| Conservators removing the darkened layers of varnish from the nave ceiling panels: the paper holds the cleaning gel in targeted areas. (Photo: Cliveden Conservation). | ||

|

||

| The nave and chancel today |

ENTERING THE church of St Mary Magdalene at Paddington, the visitor is struck by the great abundance of decoration. The chancel is particularly elaborate with every possible surface decorated, from the painted plaster ceiling to the painted brick walls, paint and gilding on every beam and column, stained glass windows and ornate alabaster wall tiles. The visitor is dazzled with a richness of colour, texture and fabric; precisely what the architect, George Edmund Street intended when he commissioned the leading artisans of the time to provide an inspirational place of worship to serve poor neighbourhoods around Paddington. This is also what made conservation at St Mary Magdalene such an exciting and diverse project.

Now Grade I listed, the church was built between 1867 and 1873 and consecrated in 1878. It is located on the Grand Union Canal, and its red and white striped needle spire is visible from Paddington Station and the Westway.

Inside, Street accentuates the highly decorative chancel and the upper levels of the nave by contrasting these elements with the austere red brick and white stone of the exterior and lower nave walls. Within the nave, the visitor’s eye is directed up to the statuary of Thomas Earp and the vast painted ceiling by Daniel Bell. In the chancel, the painted ceiling is attributable to Clayton and Bell, while the stained glass windows are by Henry Holiday.

In the years that followed, additions and changes were made to the church such as the elaborately decorated St Sepulchre Chapel by Ninian Comper (1890s) on the south side of the undercroft, and the Lady Chapel inside the transept porch by Martin Travers (1920s).

When the surrounding neighbourhoods were dispersed in the ‘slum clearance’ of the 1960s, St Mary Magdalene church became isolated. Following several decades of decay the church was placed on Historic England’s Heritage At Risk Register.

THE PROJECT

A programme of works to improve facilities and to undertake conservation was coordinated by the Paddington Development Trust and St Mary Magdalene church, supported by Westminster City Council and the Archdeaconry of Charing Cross, while funding came from the Heritage Lottery Fund and many other generous donors. A new ‘Heritage Wing’ was designed and built at the west end by Dow Jones Architects, linking the adjacent primary school with the church. This houses a kitchen, café and other facilities that enable the entire space to be used as a cultural hub for the community.

As the new building was being constructed, work to conserve and restore the original fabric of the church was commenced by Cliveden Conservation under the supervision of Caroe Architecture Ltd. The project lasted for more than six months and at its peak 17 conservators and interns were conserving the ceilings, with at least another six working to remove paint from bricks in the undercroft, repointing the exterior, and undertaking stone repairs and other works.

CONSERVATION OF THE CEILINGS

A large part of the conservation project focused on cleaning and conserving the painted ceilings in the nave and chancel.

The nave ceiling is divided into 24 bays, 12 on the north and 12 on the south side. Each of these is divided into an upper and lower tier, with painted timber ribs separating the bays. The timber ceiling is painted with bold, floral motifs using stencils, while 72 busts of saints have been painted on canvas and adhered to the substrate. These canvas paintings, or marouflage, depict female saints on the north side, and male saints on the south.

The chancel ceiling is strikingly different from the nave in form and style, with painted plaster spandrels separated by stone ribs: groups of saints are depicted at the east end, flanking the figure of Christ above the altar, while angels decorate the west end of the chancel. Here the style of painting is more delicate and narrative compared to the bold, almost cartoon-like design in the nave.

Both ceilings had received layers of varnish over the years which had yellowed with age and was now obscuring the paintings. In the case of the nave there was an even older organic varnish which had now turned dark brown. This was still visible on the ribs but it had been partially removed from the painted bays using cleaning materials that had adversely affected the paint layers, leaving numerous drips and losses. There is no record of when this cleaning intervention took place, but it seems likely that a modern synthetic varnish was applied over the bays at the same time. The same yellowed modern varnish covered the chancel ceiling too.

Varnish removals and reductions

Cliveden Conservation undertook a condition assessment of both ceilings and conducted a series of treatment trials, focusing on removing the deteriorated varnish. The most challenging aspect of this removal was finding materials that solubilised the varnish but not the paint layer below. A range of solvents and cleaning agents were trialled, beginning with the least hazardous and the lowest concentrations of materials, before gradually progressing through the available options.

It was found that the method of delivering the cleaning agents was just as important as the selection of active materials themselves. This was particularly true across the chancel ceiling, where the plaster substrate had been left intentionally uneven in order to reduce glare on the paintings from candlelight. This uneven surface meant that varnish and dirt collected in the troughs and made swabbing incredibly difficult. A selection of gelling agents, poultices and sponges were trialled to determine how best to apply conservation materials; each was held against the surface to maximise its cleaning action, while clearing the solubilised varnish and dirt from the surface with minimal mechanical action.

Various materials and methods were developed to address the organic and synthetic varnish layers of the nave. Different approaches were taken for each ceiling: in the nave, the oldest organic varnish was removed from the ribs using low concentrations of alkaline cleaning agent. This was typically applied using conservation sponges; however, where the varnish was thick and less easily removed, xanthan gum was added to form a gel which could then be left on the surface for a short period of time to increase efficacy.

The yellowed synthetic varnish that covered the painted wood and marouflage saints was extremely difficult to remove. It did not respond to most cleaning agents; some solvents caused whitening of the surface and others solubilised the paint layers almost immediately on contact. After extensive trials a mixture of benzyl alcohol and white spirit was finally selected. This was applied using xanthan gum to create a semi-viscous gel that could be left on until the varnish became grey and began to shrink away from the surface, at which point it could be carefully brushed or swabbed away. Due to the sensitivity of the paint layer, the treatment was timed to ensure that the solvent did not dwell for too long on the surface. However, it was primarily down to the skill of the conservators to monitor and remove the varnish at the optimal moment.

Removing varnish from 72 marouflage saints was a huge undertaking. These paintings had been executed off site and then adhered to the substrate using adhesive and small nails. Although they were created using templates, the placement of the figures and the size and shape of the gilded haloes demonstrate a high level of skill, as well as a fairly diverse palette and pattern range. Once the varnish was removed, details became visible that had previously been completely obscured, such as delicate facial features, attributes and drapery designs.

In the chancel, the alkaline cleaning agent was again found to be most effective at varnish reduction. In order to mobilise the varnish in the pitted plaster surface, it was found that applying the material as a gel and using brushes to agitate the solution was the most effective. As with the nave, treatments were timed but mainly depended on the skill and sensitivity of the conservator to determine how long to leave the cleaning agent on the surface, or whether a second application was safe.

While the painted wood of the nave was relatively smooth and permitted swabbing, the pitted texture of the chancel meant that achieving an even clean overall became quite challenging, so the decision was made to reduce rather than remove varnish from the chancel ceiling. As a result, instead of returning the ceiling painting to its original aesthetic (vibrant reds, blues and greens above an off-white background), the ceiling retains an element of the yellow colour imbued by the deteriorating varnish. Nevertheless, the lightening of the yellowbrown varnish was dramatic, allowing colours that had been hidden for many years to re-emerge, and the legibility of the entire scheme was much improved. The decision to retain its non-original yellow appearance does raise ethical considerations concerning the extent to which a conservation treatment should affect the original intention of the artist.

Another consequence of the decision not to wholly remove the varnish was a white bloom that developed following the cleaning treatment. After analysing a sample of the paint layer, it was confirmed that the bloom was caused by moisture trapped in the remaining varnish as it re-hardened after the cleaning process. Conservators developed a method which involved brushing the edges of an area after cleaning to ‘feather’ the remaining varnish, as well as targeting problematic areas with a re-application of the cleaning agent to further reduce the varnish.

|

||

| A gilded boss in the chancel during cleaning to remove the yellowed varnish (Photo: Cliveden Conservation) |

Retouching missing paint layers

For both ceilings retouching was kept to a minimum due in part to the fact that small areas of loss are not visible from the ground. Where loss was substantial and would hinder legibility or be distracting to the viewer, existing details were emphasised and lines continued where the design was certain. Reversible watercolour paints were used for this, sometimes with the addition of ox gall, a wetting agent, to improve adhesion of the paint. The most significant area of retouching was on the figure of St Matthew, which had sustained severe damage and loss during earlier interventions. Care was taken not to ‘invent’ any part of the composition; the saint was re-created using existing lines, matching the tone and colour of its features, such as the hair, to tone down losses.

Retouching was also necessary along the ribs towards the west end of the nave, due to more aggressive cleaning in this area historically. Watercolours were again used for the painted sections, while mica was added to Regalrez 1094 synthetic varnish to tone down losses to the gilded decoration.

Stabilisation

In addition to varnish removal other conservation treatments were undertaken. In the nave, the edges of the marouflage paintings that had separated from the substrate were re-adhered by injecting an adhesive between them, then pressing the fragile canvas back into place using gentle heat from a heated spatula, before using wooden props to hold the canvas in place while the adhesive set.

In the chancel, stabilisation was required within two south west areas that had severe damage to the paint and plaster layers due to soluble salts. Consolidation was carried out by injecting adhesive behind the flakes of paint and carefully re-adhering them using the heated spatula.

The nave, after conservation (Photo: Anthony Coleman)

The nave, after conservation (Photo: Anthony Coleman)

Cleaning the gilding

There was a large amount of gilding in the church, from relief decorations within the painted ceiling, to bands and polka dots on the ribs and beams, as well as bosses on the chancel ceiling. The cleaning solutions used on the painted surfaces were found to dull the gilding or solubilise the size below, leading to loss, so different materials and methods were sought. Swabbing with Tri Ammonium Citrate (TAC) at a low concentration effectively reduced the organic varnish and worked to return the gilding to its original colour and shine. The chancel bosses were cleaned using a proprietary cleaning solution containing synthetic saliva and TAC, which was left on the surface for a short period of time before clearing and buffing. Flakes of the gilding were re-adhered using an adhesive and heated spatula.

|

||

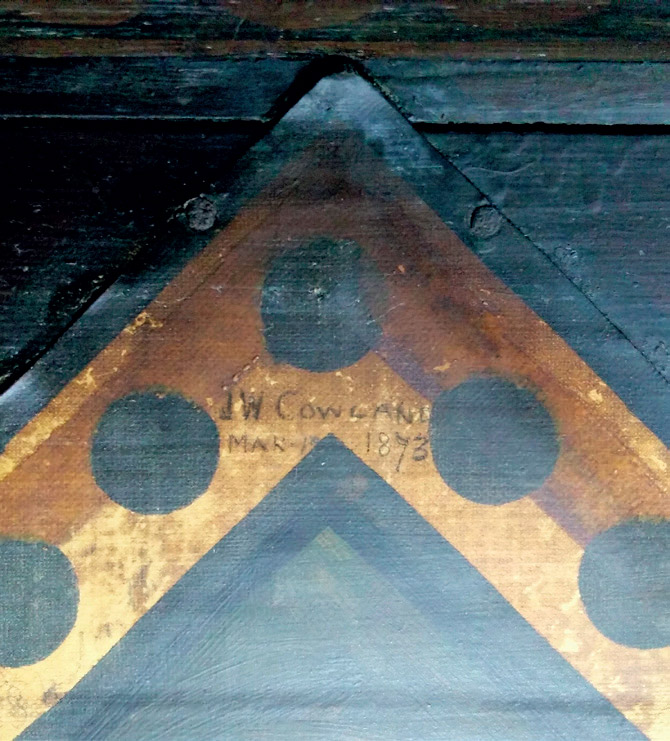

| The signature and date of an artist is visible in the centre of an internal wall. (Photo: Cliveden Conservation) |

CONNECTING WITH THE PAST

The choices made by those artists responsible for the incredibly rich decoration of St Mary Magdalene perfectly meet the challenges posed by its architectural setting in terms of distance, scale, materials and function within the religious setting of the church. Each decorative element attracts the viewer in turn and directs their gaze upwards towards the chancel. Conservation, however, revealed glimpses of the very human aspect of its decoration; artists’ signatures and notes, aids such as compass marks, templates and grids, mistakes and corrections, that give intriguing insights into the teams who originally undertook the work.

Close study of this intricately layered building provided invaluable opportunities to broaden knowledge of late 19th century architects and craftspeople. Its conservation has offered the opportunity to develop skills and to contribute to the continued joy that this wonderful church brings to the community and congregation.