Trompe l'Oeil Marble

History and Conservation of 19th-century Marbling

Francis Stacey and Jane Davies

|

|

| The Drawing Room, Osborne House: the specialist decorator Thomas Kershaw is known to have undertaken marbling here. (Photo: English Heritage) |

Marbling is a specialist painting technique that imitates the colours, patterns and lustre of polished stones and metamorphosed limestones. It has been used for many centuries to enrich the appearance of interior, and occasionally exterior, architectural elements. It may have been used when the cost or weight of genuine stone would have been prohibitive, but appears also to have enjoyed popularity as a high quality, visually appealing finish in its own right.

This article briefly describes the history of painted marbling, but focusses principally on the use, techniques and conservation of 19th-century marbling.

HISTORY

Marbling has a long history and many examples survive from the classical period, including a number at Pompeii. In the UK, archive references from the medieval period onwards record the extensive use of marbling to decorate palaces, grand houses and places of worship. It was a popular baroque motif during the 17th century and was frequently applied to columns, pilasters, pedestals, chimneypieces, wainscots, door architraves and staircases.

Marbling declined in popularity during the first half of the 18th century but was reintroduced during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It became very widely used during the 19th century and even today thousands of humble Victorian terraced houses retain marbled panels as part of their original fireplaces. Grander buildings often contain examples of more impressive features including entire ‘marbleised’ staircases – an early example, from the beginning of the 19th century, can be seen at Sir John Soane’s Museum, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, London.

Marbling techniques grew in sophistication over time. Very early examples tend to use opaque colours and are decorative allusions to patterned stone as opposed to trompe l’oeil illusions. The primary intention was perhaps to add a sense of opulence, enlivening surfaces with colour and pattern, rather than to imitate the fine detail of stone. By the mid-19th century, however, examples using diluted opaque paints and transparent glazes applied with a variety of brushes and subtly manipulated with feathers, leathers and rags, were being produced which could pass for real stone, even to an experienced eye.

During the 19th century, artist decorators who specialised in faux painting techniques could earn substantial sums and great status through commissions from wealthy clients and their work could receive plaudits from civic and professional bodies. For example, apprentice decorator Thomas Kershaw (1819-98) saved enough to purchase specialist painting tools and moved from Lancashire to London in 1845. He won first prize for his marbling examples at the Great Exhibition in 1851, and gold medals at the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1855 and the International Exhibition of 1862.

Kershaw set up his own firm and won numerous commissions including marbling at Buckingham Palace and Osborne House. He became an elected liveryman in The Worshipful Company of Painter-Stainers, was granted the Freedom of the City of London in 1860 and died a prosperous gentleman. Examples of his work can still be seen on the staircase to the British Galleries in the V&A Museum and at Bolton Museum, Lancashire.

|

|

|

||

| Left: a recently painted example of Brèche violette showing the typical dark purplish broad veins and very fine white veins worked over a pale cream ground. Centre: a brèche violette panel being worked with a sponge to modify surface glazing. Right: A plinth dated to the late 19th century on stylistic grounds. It is probably a demonstration piece intended to display a range of different marble finishes and may have been produced by an apprentice painter as his masterpiece. | ||||

19TH-CENTURY TECHNIQUES

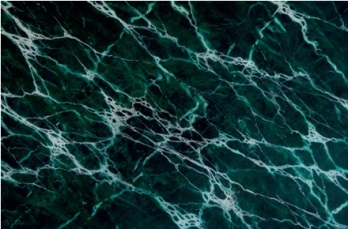

Decorative marbles were categorised by various types, the main ones being: laminated, brecciated, crinoidal, serpentine and variegated. Each has its own distinctive range of shades and textures and many are naturally decorated by colourful veining or the inclusion of fossils.

By the 19th century, students were expected to study geological specimens to produce imitations that were as realistic as possible. As the best quality marbling was intended to be highly naturalistic, painting techniques evolved which relied on the use of transparent layers to create visual depth. Writing in 1878, the master painter-decorator AR Van der Burg commented: ‘the marble-painter must take it as a fundamental rule that marble, the colour of which is transparent, can only be imitated by glazing or some similar process’.

For marbling to have the waxy sheen associated with polished stone, the surfaces to be decorated had to be carefully prepared to present a very smooth surface. The preparatory layers of priming and ground layers would consist of a drying oil binder (usually linseed oil) and pigments such as lead white, rubbed smooth once dry.

Grounds also had a colour function and would influence the appearance of the translucent patterning paint. The majority were off-white but a few, such as vert de mer (a dark marble with green veins) and ‘black and gold’ (a black marble with gold veins such as Porturo), would have a dark colour ground.

|

|

| Paint sample from the imitation violet marbling on the shaft of the plinth illustrated above. On the photomicrograph the off-white ground, smooth on its upper boundary, is coated by a violet layer, modified on its surface by translucent white glazes. A discoloured varnish layer is visible on the surface of the sample. Chunks of red lake and dark purple mortuum kaput are visible. |

Paradoxically, recommendations for some dark marbles suggested a light ground, so the techniques can be carried out as light over dark or dark over light. The surface of the ground would be worked over (or ‘clouded’) using either well-diluted opaque or naturally translucent pigments in order to create irregular and varied patches of colour, copying the natural appearance of the marble.

Any visible brush strokes would be softened with a badger-hair brush. The shades of the principal colour were applied to look ‘either like lumps, veins or plain spots, intersected here and there by dark, lighter or white veins’. The correct application was clearly a skilled job despite its deceptively natural appearance. Van der Burg comments ‘the paint is loosely put on in a rolling way; the more freely and artlessly this is done, the better it will serve the purpose’.

A variety of brushes were used: the ‘spotting or marbling’ brush, flat ‘French’ brush, round ‘mop’ brush, sable brush (or pencil brush), glazing brush (a wide but thin brush) and a flat, long-badger-haired brush serving as a softener. The broad veins were put on with the flat French brush or the glazing brush, the finer veins with a sable brush, gently softened to one side with the badger brush, giving the effect of one hard and one soft edge to the veins. Van der Burg also describes an interesting technique where the marbling brush is dipped in turpentine and pressed out on the edge of the cup so that its bristles are splayed, the brush was then dabbed into sequential colours on the palette so that ‘with one stroke these different tints may be laid on sharp or flowing’.

Techniques such as spotting (covering both light and dark parts with spots of diluted paint) allowed the marbling to be subtly augmented and the softening brush was used to ensure that no unintended hard edges were present. Once these had dried hard, a glazing coat of paint ground in oil and well diluted with turpentine was applied to give the desired transparent tint and to make subtle enhancements to the design. The glazing layer was further worked with additional diluted paints. It could also be partially wiped out with a rag, a ‘veining horn’ (a rolled soft leather cloth or a piece of wood with a rounded end) or a natural sponge to modify its appearance.

Binding media

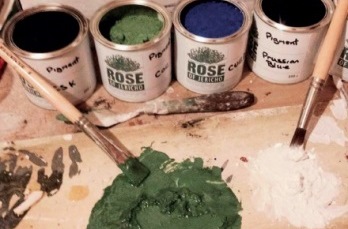

In common with both 19th-century architectural painting practice and easel painting techniques paints for marbling were made from pigments ground into a drying oil and diluted with turpentine. Normally, linseed oil was used as it was capable of forming a relatively quick drying and strong paint film, especially in combination with siccative pigments, such as lead white. Victorian treatise recommend, again as was common practice, the addition of a little boiled oil or driers if slow drying (non-siccative) pigments, such as mortuum caput or vine black were to be used. Some authors suggest the use of poppy oil with white pigments such as zinc white, as it was less prone to yellowing than linseed. However, in well-lit rooms or exterior work, linseed oil was recommended as best for all whites as it formed more durable paint.

|

|

|

| Above left: a recently painted example of marbling in imitation of green vert de mer marble, which owes its name to the form of its veining which suggests the waves of the sea. This was an expensive marble and was often imitated during the 19th century. Above right: Dry pigments are ground into linseed oil to form a paint paste that is then diluted with turpentine for application. | ||

Water colour may also have been exploited to produce effects not easily obtainable in oil, often in the preliminary stages, and the work completed in an oil medium, with perhaps a final glaze in watercolour.

Pigments

The pigments used were those generally available to the Victorian artist, while sensible economies were made in order to respect the size of faux marble panels to be prepared and the consequent costs. For example, in recommending pigments for Brèche violette Van der Burg lists zinc white, black, ochre, chrome-orange, red mortuum caput (a purplish iron oxide), ultramarine blue and organic red lake pigments. He goes on to say:

The painter knows very well that lake fades away by a strong light and that the colour which is of great importance in this marble should be durable. We therefore advise to paint a work, which is much exposed to the sunlight, with caput mortuum as much as possible, and to use the fading (organic lake) colour as little as possible, though it cannot entirely be dispensed with…

Varnishes and waxes

Varnishes were applied to intensify the appearance of the paint layers and to provide a degree of protection to the delicate surface finish. By the 19th century spirit varnishes produced by dissolving tree resins, such as dammar or mastic, in solvent were widely used. Traditionally varnishes are clear, however, their appearance can be modified by the addition of pigments and other materials. The inclusion of wax, for example, produces a less glossy varnish film. Natural waxes were also used to give a saturated polished look to marbled surfaces.

CONSERVATION

Many examples of Victorian marbling survive in historic buildings, but this does not detract from its significance. Many of these examples are in reasonable condition and can simply be maintained and cared for using preventive conservation measures. However, as with all architectural painting, faux marbling is part of the building structure and is especially vulnerable to moisture both as a fluid (entering through leaking roofs for example) and from cycles of changing relative humidity (caused by fluctuations in visitor numbers for example). At a low level it is often subject to abrasion through everyday use, and occasionally damage occurs due to well-intended but ultimately destructive routine cleaning.

Advice from qualified conservators is essential if any conservation or redecoration is being considered. Interventive treatments such as conservation cleaning to remove discoloured coatings need to be considered carefully given the multi-layered composite nature of the technique. The application of highly diluted glazing results in thin layers which are vulnerable to solvents and cleaning agents. Original protective varnish layers may have been re-worked so that part of the design may overlay the varnish.

|

|

|

||

| Left: Castle Howard, Long Gallery, c1811: uncovering trial following paint sampling, revealed painted marbling on a pilaster skirting, which was intended to match the fossil marble of the mantelpiece. Centre: detail of the fossil marble mantelpiece in the Long Gallery. Right: Paint sample from the imitation marbling. The paint sample was prepared in cross-section, polished and photographed under dark-field reflected light at 200x magnification. The upper white and pink surface layers date from the 20th century. The orange red layer is from the late 19th century when the room was wallpapered. The thin translucent dark layer is varnish, over pink grey on a grey ground. | ||||

The use of organic pigments can result in irreversible fading upon exposure to ultraviolet light. In contrast, the use of linseed oil as a paint medium can result in darkening and yellowing of the paint in areas with poor natural light. Original or later applications of resin varnishes will have a tendency to darken over time but attempts to remove them may jeopardise the thinly applied glazing layers below. An understanding and acceptance that marbling will almost inevitably have altered in appearance with time should underpin its preservation. However, marbling was often waxed after completion and a light cleaning and re-waxing can achieve good results.

If there has been damage and loss to areas of marbling, highly skilled decorator/ conservators can recreate the design. Law restricts the use of certain historic pigments, such as lead white but obsolete or unobtainable pigments can be replaced with substitutes. Where marbling has been damaged this can be coloured in, or where larger sections have been lost these may be worked into blending old with new, using intervention layers like synthetic varnish to separate the original and the repair.

Recommended Reading

H Binns, ‘A History of the British Decorators’ Association’, British Decorators’ Association, 1994

I Bristow, Architectural Colour in British Interiors 1615-1840, Yale University Press, London, 1996

J Fleming and T Taylor, The Life and Times of Ernest Dobson, Grainer, Marbler, Decorative Painter, Fleming & Taylor, Clitheroe, 2006

A Roy and P Smith (eds), International Institute for Conservation 1994 Ottawa Congress: Preventive Conservation – Practice, Theory and Research, Archetype Publications, London, 1994

AR Van der Burg and P Van der Burg, School of Painting for the Imitation of Woods and Marbles etc, London, The Technical Press Ltd, 7th edition, 1936