Material Assets

Rob Robinson

|

|

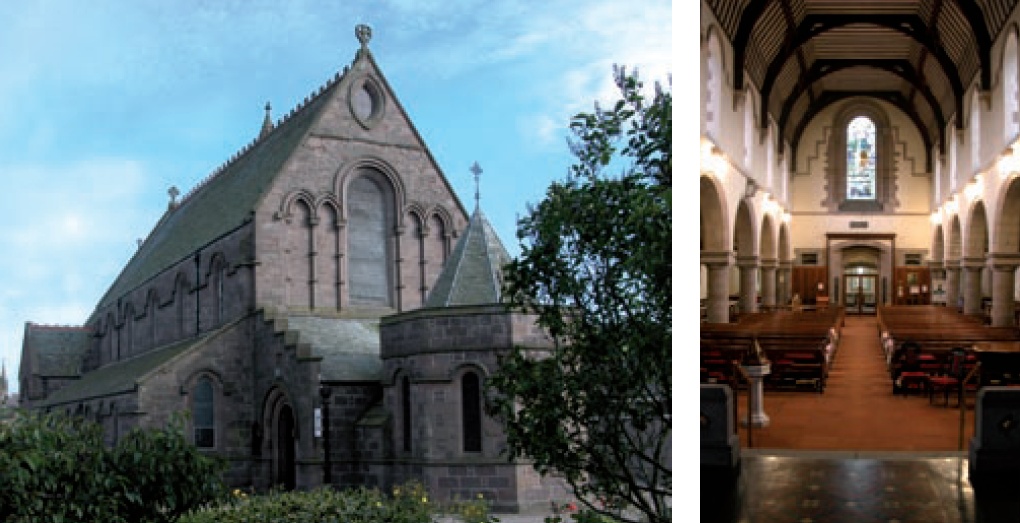

| St James's Church, Stonehaven. The empty nave (right) could be reinvigorated by careful adaptation to incorporate church hall facilities |

Many of our most treasured churches are in a perilous financial situation and brave decisions are required to secure their future. The proceeds of the beetle drive fall far short of meeting the repair costs for the roof, the heating or the damp walls, and it is becoming increasingly common for our historic churches to look beyond the obvious for sources of income. For many churches it is time for the irreversible decision: what can we sell? As in a game of Monopoly, selling assets is generally a last resort but it can often provide a great opportunity to save the church, release capital for better investment elsewhere and, importantly, reintegrate the church back into the heart of the community. It may even draw in a few new members to the congregation along the way.

There is no denying that a considerable proportion of our historic churches are facing some degree of financial crisis, and while the isolated parish church may be suffering most, many of the UK’s urban churches are facing equally troubling times. At its simplest, the cost of repair and maintenance outweighs the income generated and any funds held in reserve. The problem is exacerbated by the growing costs of conservation and building work and the falling numbers of people attending or using the church; the latter is frequently a result of external forces, such as the changing demographics or land use of the surrounding area, but it can also be a result of the church failing to fully engage with its community.

Churches that do not have the tourist pulling-power of York Minster or a Dan Brown connection cannot charge for admission, and the voluntary contribution of visitors and the occasional postcard sale is a poor substitute. Fundraising on a major scale is the principal alternative, and the best results will be achieved by using a professional fundraising body. But it’s often easier, quicker and more certain to release capital from – dare I say it? – leasing or selling off historic fabric, if the church and congregation can stomach it.

Whichever approach is adopted, the importance of historic fabric as an asset must be considered. Generally the first choice is to examine ways of generating income while retaining all assets through leasing part of the building to a worthy enterprise. At Bangour Village Hospital Memorial Church in West Lothian this was investigated and the most profitable option was to adapt and lease the north range as office space.

Providing that a large sum of money is not needed quickly and that the nature of the church buildings is suitable, leasing can be a good option. It provides a steady and long term source of income, increases the use of the church, particularly amongst those who may not normally attend, enables the retention of all assets and can bring benefits in the form of small businesses with new skills, such as website developers, accountants or event co-ordinators.

Unfortunately, more money is often required and more quickly than leasing can deliver. In some cases selling property may be an option. The greatest single asset other than the church itself is often the church hall. There are many examples of churches of varying sizes where the hall and its functions have been successfully amalgamated into the body of the church, and the notion is well championed by Sir Roy Strong in his book, A Little History of the English Country Church.

At St James’s Church, Stonehaven, after careful consideration the recommended option was to sell the hall for residential development and move the hall function inside the church. Despite church and hall both being fairly well used, neither was anywhere near capacity. With a renegotiation of time slots, the functions of both buildings could be brought under one roof with a variety of additional complementary uses. A clever architectural approach by Simpson & Brown Architects has made incorporating the hall’s functions within the church relatively easy: the challenge will be to negotiate planning permission for building a small apartment complex on the site of the church hall. Although a precedent is close by in the form of a converted building, the new development would be much closer to the listed church.

|

|

| The old school house, St Andrew’s Cathedral, Aberdeen |

‘Enabling development’ as it is known, is a common recourse for owners of a wide variety of historic buildings. As a result, English Heritage published useful guidance on the issue in 1999. This document states that the capital to be released through the development should not be available from other sources, and that the profit from the development should not exceed the amount needed to safeguard the asset. Clear guidance such as this can be helpful when considering the options available, although in Scotland, from where the examples have been drawn in this article, there is no such standard approach and all sites are considered very much on their own special circumstances.

Churches frequently possess other assets beyond the hall, such as rectories, schools and plots of land. Any ancillary buildings owned by a church often simply pass from use to use generating a small (and decreasing in real terms) income, slowly falling into a state of disrepair; as the conservation needs of the church take priority. At St Andrew’s Cathedral in the heart of Aberdeen, the diocese’s holdings include the old school and a row of historic residences (now the John Skinner Centre), both of which have in part been adapted and reused by a visual arts organisation. An economic development study investigated a number of short and long term routes to finance with the objectives of providing capital for essential conservation needs, a reasonably secure long term source of income and to further the church’s mission and place in the community.

The study investigated a number of options for the buildings with a variety of uses, ownership shares and routes to development and culminated in a ten-point plan to take the project forward. The recommended option comprises a major mixed-use development including the retention of ownership of the old school and the north part of the John Skinner Centre, and the sale of the southern part of this building.

A major development project like this is, quite rightly, a very daunting prospect and raises the important question; how will the church or cathedral go about making it happen?

Most rectors are not natural property developers: the two roles have little in common and require very different skill sets. Bearing this in mind, as well as the usual need for developer finance, it is generally recommended that the church employs an independent property developer or development consultant to act on its behalf. As at St Andrew’s, this person can prove invaluable as a negotiator and advisor in setting up the partnership and contract between the church and the selected developer who will take the project forward.

|

|

| The site of a recommended mixed-use development at St Andrew's Cathedral, Aberdeen |

In the case of St Andrew’s, the cathedral is well placed; located centrally within a desirable city that commands high property prices. This creates a number of options and generally means that the cathedral and developer will be able to achieve good returns on investment over the short term through sales, and the longer term through rents. However, not all churches are so lucky.

St Salvador’s in Dundee, one of G F Bodley’s seminal urban churches, is a good case in point. Surrounded by tightly packed tenements when it was built, the Hilltown area in which it sits has seen a gradual change towards light industry and the construction of tower blocks which are now becoming increasingly vacant as they reach the end of their lives. Consequently the local community from which to draw on has gradually declined, leaving the church increasingly disengaged.

The diocese has a number of assets including the rectory, a hall, an old school building and a vacant plot of land. Despite having more land and buildings to consider and a greater flexibility of use due to the nature of the site, maximising the assets’ financial potential faced a crucial problem – the land value and any subsequent property sale values were simply too low to generate a worthwhile return on investment. The only way in which a development would be viable was for a housing association to act as developer, utilising Housing Association Grants to build a Homestake Housing scheme. The recommendation in this case was to sell only the vacant plot of land to a local housing association which was already involved in a development on an adjacent site and to use this money to make enhancements to the church hall to enable greater community use.

The low land and property values in this project meant that, despite having a number of assets, their sale would not create a sizeable lump sum for conservation. The capital released would, however, enable the church to more fully engage with its community through its hall and over the long-term it gains from a secure income through rents. However, the conservation of the church will still require a major fundraising campaign.

Just as each church is different, each financial crisis is best met with an approach specific to the needs, circumstances and assets of that church. There is no one-size-fits-all answer. Where the sale of a property seems to provide the solution, remember of course that once it’s gone, it’s gone, and that applies to both the church and its associated assets. The questions will be: is it worth sacrificing the old school, the hall or the rectory to save the church? And is there really no alternative? In the end, however, the sale of an asset can give the church a new lease of life and help it to play a fuller role in the community as it takes on additional functions, which surely has to be a good thing.