Medieval Stained Glass in North Wales

and its treatment in the 19th century

Martin Crampin

|

|

| The Annunciation, Clayton & Bell, 1872, lady chapel (north aisle), Church of All Saints, Gresford, incorporating glass of 1498 (All photos by the author) |

It has long been known that a significant body of medieval stained glass survives in the churches of north Wales, and in particular in Flintshire and Denbighshire. This glass was recognised and studied in the 1960s by Mostyn Lewis, whose Stained Glass in North Wales up to 1850, published in 1970, has remained the best source of information on the subject, despite lacking the colour photography necessary to excite the layman.

Mostyn Lewis realised that this survival was significant since, for reasons still not well accounted for, medieval stained glass is rare in the southern half of Wales, and although there are some 14th-century survivals, stained glass of the late 15th and early 16th centuries, which makes up so much of the medieval glass in north Wales, is quite scarce across the border in Cheshire. To put the quantities in context, perhaps a third of all the medieval glass in Wales survives in a single church, at the Church of All Saints, Gresford, near Wrexham. Furthermore, it would easily be possible to fit all of the medieval glass from Gresford into the recently restored east window at York Minster.

The reasons why medieval stained glass has survived in some parts of the country and not in others are often obscured by our lack of knowledge about how widely stained glass was adopted for the glazing of church windows in the Middle Ages. Furthermore, there are several reasons why stained glass was lost or destroyed in the intervening centuries.

Along with rood figures and statues, stained glass was certainly taken out or attacked during the religious upheavals of the mid-16th century. While I expect that this may have happened in Wales – and certainly devotional figures were removed – I have not yet come across a single reference confirming it. Stained glass from monastic houses was particularly at risk, as the fabric of the buildings was sold off as a valuable commodity. For example, at the Cistercian house of Strata Marcella near Welshpool, stone, lead gutters, window glass and lead were sold off as well as bells, the organ, plate and vestments. Not surprisingly, there are no visible remains of the abbey today.

Several 19th-century and earlier traditions claimed that stained glass in parish churches was brought there from neighbouring monastic houses. However, it is more likely that most of these stained glass windows originated in the churches where they are now found, rather than being moved to new locations in the late 1530s. There is better evidence for the destruction of stained glass during the English Civil War, however. Parliamentarian troops were known to have destroyed windows in Wales from Hawarden to St Davids, and the belief that the famous Jesse window of 1533 at Llanrhaeadr-yng-Nghinmeirch in Denbighshire (illustrated below) was removed and hidden in the 1640s may have some validity, as it might not have otherwise survived the presence of Parliamentarian troops in the area in 1646.

The descriptions of churches in Wales written by the antiquarian Sir Stephen Glynne in the 1840s reveal that much more medieval stained glass existed in Welsh churches then than it does today. Together with other written and visual sources from the early 19th century, this demonstrates that losses of medieval stained glass continued well into the 19th century. Consequently, the neglect and loss of old stained glass can potentially be dated to the time when medieval churches were transformed during the great period of restoring and rebuilding in the second half of the 19th century.

|

|

| One of two saints, probably second quarter of the 14th century, in the sanctuary apse of St Mary’s, Treuddyn |

A scenario that illustrates the potential for the loss of medieval glass in the period is recorded in a letter to the Church Restoration Building Committee at Treuddyn, Flintshire. In 1875, the architect, George Vialls, wrote to the committee asking whether they would like the medieval glass salvaged from the old church, before the building was demolished to make way for the rebuilt church. ‘The old work is chiefly made up of odd pieces’, he wrote, ‘but there are some parts of figures that are tolerably perfect’. Use of the old glass, he pointed out, would decrease the amount of new glass that would need to be purchased, and would effectively preserve the old glass ‘& a very good effect of colour at the East end would be gained, although the actual pattern would be for the most part irregular & undecided’. In this instance, the committee evidently decided to have the glass returned, and because of that the earliest figures in stained glass found in Wales survive at Treuddyn (right). Elsewhere, there were no doubt instances where it was decided that the ‘irregular & undecided’ pattern of old glass was not desirable, and thereafter left in a glaziers’ studio or builders yard and ultimately lost.

The church at Treuddyn is one of two churches in the area that have graffito recording the re-leading of stained glass in the late 18th century. This is perhaps another clue to the reasons why some medieval stained glass survived and some did not. The need for re-leading in the 17th or 18th centuries, when coloured pictorial glass of the Middle Ages would not have been valued or admired, may elsewhere have resulted in the decision to discard it in favour of clear quarries. This attitude probably continued into the 19th century in some instances, which would explain why fragments of scenes and figures known in the 1840s seem to have disappeared by the end of the century.

In the process of preserving medieval stained glass, a variety of approaches were employed, and several main methods characterise its survival in churches today. In a few cases, sufficient fragments have survived to enable the reconstruction of a complete window, with either new painted pieces or clear glass inserted to fill in the gaps between surviving parts. Where less glass has survived, these fragments have sometimes been inserted, fairly seamlessly, into entirely new creations made of new painted and stained glass. Alternatively, when there have not been enough fragments to make sense of any larger design, fragments of painted or stained glass, and sometimes unpainted coloured pieces, have been leaded together to make what we would now understand as an abstract design, although when this was done in the 19th century it predated our contemporary appreciation of the aesthetics of abstraction that developed during the 20th century.

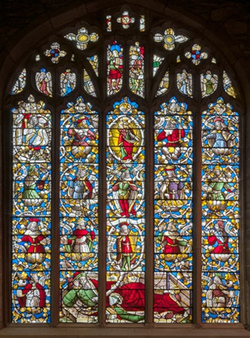

The nearest that we have to a complete medieval window is the justly famous Tree of Jesse at Llanrhaeadr-yng-Nghinmeirch (below). If the window was indeed removed at the time of the civil war, its return to the church might have ensured that the renewed lead and supports would hold it in place for another couple of hundred years. Even here the window is not a single work. There is some slightly earlier work in the tracery lights, which was probably left there when the Jesse Tree was installed in the main lights in 1533.

Remarkably, the other near-complete Jesse window at Dyserth in Flintshire can also be dated to the same year, although the style is different. This window also has figures of a slightly older style in the tracery lights, and in each of the lower sections, where the Jesse figure would have reclined, there is a jumble of assorted medieval glass. This seems to consist largely of decorative surrounds, rather than any part figures, and there has been no attempt to join pieces together at all.

|

|

| The Tree of Jesse, 1533, north chancel, Church of St Dyfnog, Llanrhaeadr-yng-Nghinmeirch, Denbighshire | |

|

|

| Female figure, possibly the Virgin Mary, mid-15th century, nave, Church of Corpus Christi, Tremeirchion, Denbighshire |

We can see evolving attitudes to the preservation of medieval stained glass at Gresford. In the late 18th century, the east window of the chancel was ‘entirely filled with confused remnants of painted glass’ but was restored by the Victorian firm Clayton & Bell in 1867. It was decided that the stained glass should be completely reset, using new glass to reconstruct what were thought to be the original subjects of the window. There were clearly enough remains of the seven main figures in the upper main lights to be sure of their place in the window, but only supposition determined that above there should be a Tree of Jesse, and below the figures representing the Te Deum, although this assumption was still based on what was found in the window. To reconstruct these groups of figures a large amount of new painted and stained figures were made by Clayton & Bell, using an antiquated style to match the late Gothic work of 1500, the date that the east window was commissioned by Thomas Stanley, first earl of Derby.

When the firm returned to the church to restore the east window of the Lady Chapel in 1872, there was clearly more of the original window in situ, including the details of its donation and its date of 1498. This included some near-complete scenes, which in the main lights depicted scenes from the life of the Virgin. Scenes such as the Annunciation creatively use fragments of the 1498 window in compositions largely of 1872, while the Nativity and the Flight to Egypt use hardly any old glass. However, this tendency to fill in gaps was not used when the Trevor Chapel east window was restored in 1915-16. In this window, Clayton & Bell filled the gaps within the four central scenes, two from the life of John the Baptist and two from the life of Anthony, with pieces of clear glass rather than attempt to recreate the missing features. In addition to these principal windows, other windows in the church and porches are filled with fragments which do not generally make sense of them, but were presumably brought together in such a way as to preserve as much of them as possible while still leading them together.

Elsewhere in north Wales we can see these different approaches followed for the preservation of medieval glass. At Llangadwaladr on Anglesey, what appears to be a complete medieval window is in fact only partly medieval. The three-light window of the Crucifixion with Mary, John and donors was patched so skilfully in the mid-19th century, that it is very difficult to tell how much is in fact medieval. By contrast, the east window at the Church of St Mary, Nercwis, in Flintshire, is a 19th-century window, incorporating just a few medieval fragments, such as the head of a saint, some angels and a heraldic lion. The presence of a boar on the opposite side of the lion has suggested a date of 1483-5 for the fragments, the period of the reign of Richard III, but as the boar looks more likely to date from the 1883 restoration by Burlison & Grylls, it may perhaps be a copy of medieval glass that was in too poor a state to preserve, as it would be a curious invention. Hunting for medieval fragments in large Victorian windows such as this might even raise the possibility that perhaps more medieval fragments are yet to be identified among the modern windows of restored medieval churches.

There is little semblance of a complete window at Llandyrnog, where glass from more than one window has been brought together by Charles Eamer Kempe in the east window of the chancel. Here the tracery figures probably occupy their original positions, and while the crucified Christ occupies its original central place in relation to the surviving panels representing the seven sacraments, three of which are still joined by lines of red glass to his wounds, other parts of the window are a jumbled assemblage of figures and other fragments brought together in rectangular panels. The filling of these rectangular panels sometimes emphasises the shape of a figure while patching up the scene with unrelated fragments. This can be done with shaped pieces of decorative borders and canopies. For example, at Tremeirchion in Denbighshire the head of a female figure (above), probably that of Mary, has part of a cruciform halo in silver stain over it, the other half comprising silver stained pieces of decorative patterning, and some feathers, probably from an angel.

Although there is considerable diversity in the way in which medieval stained glass has been preserved in the windows of restored and rebuilt medieval churches, its survival into the 21st century should be celebrated. While we might lament the loss of ‘large figures of saints’ at Llanfair Dyffryn Clwyd seen by Stephen Glynne in 1849, a large number of jumbled fragments collected in a south window do at least offer us a few clues to their identities, and a probable date of 1503. In many other cases, nothing at all remains of those vibrant expressions of medieval faith from other churches, lost to iconoclasm, the elements and neglect.

~~~

Further Information

M Crampin, Stained Glass from Welsh Churches, Y Lolfa, Talybont, 2014 (below)

M Lewis, Stained Glass in North Wales up to 1850, John Sherratt & Son, Altrincham, 1970

|