The Mausolea & Monuments Trust

A small charity with a very big mission

Roger Bowdler

|

|

| The Nash mausoleum at Farningham, Kent: one of the Mausolea and Monuments Trust’s early acquisitions |

The highly-esteemed director of the Soane Museum, Tim Knox, once described the Mausolea and Monuments Trust (or MMT) as ‘the dottiest conservation cause in the land’. Speaking then as the chairman of the MMT, he knew as well as any the daunting challenge faced by the fledgling charity in its attempts to make a difference in the realm of funereal architecture. Most readers will be well aware of the issues facing graveyards and cemeteries in terms of the conservation deficit. They will also be aware of some of the worthy endeavours to rescue collapsing tombs at a local level. This article looks at the work of a national charitable body that was set up to address one of the most serious conservation causes: the plight of the mausoleum.

The MMT was set up by the late Dr Jill Allibone (1932-1998) in 1996. The authority on the Victorian architects George Devey and Anthony Salvin, and a long-time stalwart of the Victorian Society during its campaigning heyday, Jill had identified a particular issue attending the nation’s many mausolea. In short, their legal owners didn’t want to know about them. Often of exceptional design quality and intricacy, they were frequently seen as irrelevant encumbrances by their reluctant inheritors. More demanding in terms of maintenance than most memorials, these little buildings devoted to the dead (as specific a definition for this building type as we probably need) require regular inspection and upkeep. As the excellent MMT gazetteer of mausolea (compiled by Teresa and David Sladen) illustrates, many of them are now in poor condition.

MAUSOLEA IN DECLINE

Why are mausolea a problem? What are the particular issues that attach to them? At least four issues can be identified.

First of all, the mausoleum is as far removed from the humble grave as it is possible to get. All monuments are tributes to vanity, as well as to love and memory. This is particularly true of mausolea: they are among the most self-serving and attention-seeking of all building types. A sort of post-Reformation successor to the chantry chapel, they are private structures devoted to exclusive family use. Inside their strong walls are limited places for the deposit of stoutly coffined remains, placed on pantry-like shelves. These were dynastic buildings, marking out the family resting place from the rest of the Anglican congregation, which was generally placed in the ground to mingle in the dust as a final act of parish communion. Some of the grandest mausolea were built in private grounds, thereby marking an even greater separation from the church and graveyard. Mausolea were thus deliberately exclusive and private: as archaeologists say, they were ‘high status’. Some might see their decline as striking a note of hubris.

A second, related point is the very privacy of the buildings. As the embodiments of dynastic pride and lineal provision, they are strongly connected to the concept of the family. Legal responsibility for the upkeep of memorials descends to the heirs-at-law. If we stop to reflect on the mobility of modern society and the infrequency of direct succession to estates, we soon realise the likelihood of memorials becoming the charges of quite distant descendants. Some of us may be legally responsible for monuments while remaining utterly unaware of that responsibility. This is not always the case: the Earl of Yarborough attends to the superb Wyatt-designed mausoleum at Brocklesby, dating from the mid 1790s, and the Molyneux family has recently renovated the imposing Gothic octagon in Kensal Green Cemetery, designed by John Gibson in the 1860s.

But for every monument or mausoleum in regular receipt of active care, there are many which languish. To all intents and purposes, they have been abandoned. How many of us are aware of the burial sites of our forebears? The family burial plot is less important a marker of status and continuity than it once was, and the mobility (both geographical and economic) of modern society discourages us from the age-old rituals of grave attendance and upkeep. In practice, then, how many monuments have any practical guardians? Genealogy might be opening up family connections at a faster pace than ever, but full legal responsibility for the maintenance of monuments is a very rare spin-off. There is a void of care in this area which it is hard to overstress.

Is it right to expect parishes to make up for this deficit? Probably not. Congregations face a daunting task in keeping church buildings in a fit state of repair, and the days of the sexton, busying himself with stitch-in-time maintenance as well as the digging of graves, are well and truly over. It is all too easy for graveyard maintenance to end up near the bottom of the parish list of priorities; and the higher-than-average maintenance demands of a mausoleum make it all the more likely to be sidelined or forgotten.

|

|

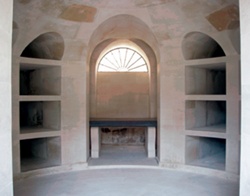

| The restored crypt of James Wyatt’s 18th century Darnley mausoleum at Cobham, Kent

|

A fourth factor which operates against the mausoleum is its uncertain status as architecture. Too small to be a proper building, and all too often locked up, it falls outside the run of conventional appreciation. A residual unease surrounding death and mortality still lingers in modern society, despite decades of discussion on the subject. The MMT’s late patron, Sir Howard Colvin, published Architecture and the Afterlife in 1991; its present patron, James Stevens Curl, wrote A Celebration of Death as long ago as 1980. But these things aren’t everybody’s idea of merriment, and we must accept that matters funereal are probably a minority interest. All the more important, therefore, to make the case for this particular building type. Not only are they some of the most atmospheric of structures, they can possess design quality of a very high order indeed. The unforgettable Darnley mausoleum of 1785, designed by James Wyatt at Cobham, Kent, has just benefited from a major programme of restoration funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund. Its crisp classical pyramidal profile is once more secure after decades of decline. However, a brief look at the latest English Heritage Heritage at Risk publication will reveal many mausolea in a much less happy condition.

STEPPING INTO THE BREACH

The widespread attitude of acceptance towards decay and decline in grandiose monuments; questions surrounding family responsibility for these buildings; the inability of parishes to take on the burden of caring for them; and the prevailing unease with death: these are the main factors specific to the mausoleum which contribute to their present and lamentable lot, as Jill Allibone recognised in the mid 1990s. The scale of the challenge is therefore daunting. What can be done?

Jill’s vision was for a body which would step into the breach. It would use its conservation alertness to concentrate on worthy candidates, and assume responsibility for the friendless structures. It would draw on its knowledge of conservation organisations and processes, and apply for grants. It would campaign to bring the plight of mausolea to wider attention. And it would employ the best of architects and conservators to carry out works which would be of enduring benefit to the structures in question.

|

|

|

|

| The exterior of the Sacheverell-Bateman mausoleum, Morley, Derbyshire (top); and restored stained glass inside the mausoleum (below) |

Candidates for acquisition quickly presented themselves. Foremost among them was the Sacheverell-Bateman mausoleum at Morley, Derbyshire. Designed by G F Bodley and built in 1897, the refined Gothic structure was conserved over a ten year period at a total cost of just under £50,000 (a whisker under the original estimate). Anthony Short and Partners, a respected Midlands practice, were the architects; Mark Parsons was the lead partner. With elaborate glass by Burlison and Grylls, complex ironwork, extensive masonry repairs and re-roofing all being called for, this was clearly a demanding case with which to open the MMT’s account. In keeping with the wishes of the founder, a thorough job was carried out. The roof was replaced in tern-coated steel as a security measure, and it is hard (in this age of soaring scrap values) to rue this decision. A major grant from English Heritage was vital in making the project happen, as was the commitment of Teresa Sladen, who took over many of the responsibilities following Jill Allibone’s death in 1998. The result is an exemplary scheme and a secured mausoleum, which honours the memory of the MMT founder as well as that of the Sacheverell-Batemans.

Other early acquisitions included the Nash mausoleum at Farningham, Kent and the Wynne Ellis mausoleum at Whitstable by Charles Barry junior, acquired in 1997. Wynne Ellis of Tankerton Tower lies within a massive battered sarcophagus, with steps leading to the burial chamber below. Its doors were damaged and its security threatened, so the MMT re-made the doors, using the original bronze grilles and whatever timber could be salvaged, and has carried out regular sycamore clearance within the enclosure. The Nash mausoleum, erected in around 1778 for the uncle of architect John Nash (and quite likely an early work of the great Regency architect), was taken on by the MMT after the death of the last surviving trustee and restored with the help of English Heritage, Sevenoaks District Council, the Pilgrim Trust, the Leche Trust, the Georgian Group, and the MMT’s own (pretty limited) funds.

More recently, the 1771 Heathcote mausoleum at Hurley, Hampshire, entered into the MMT’s care, and has recently been fully conserved at a cost of £58,000 thanks to grants from Hampshire County Council and Winchester City Council, which permitted the brickwork to be re-pointed and the complex domed roof to be re-covered. The Guise mausoleum at Elmore, Gloucestershire is an important early neoclassical structure, built after Sir John Guise’s death in 1732, with baseless Doric columns supporting a pyramidal roof. Only the lower parts of the columns remain standing: of all of the MMT’s holdings, this is the most challenging. Most recently, in April 2008, the Boileau mausoleum at Ketteringham, Norfolk joined the portfolio. It came to us through the offices of the late chairman Dr Thomas Cocke, an eminent architectural historian. The Boileau mausoleum was transferred to us after a very impressive programme of restoration undertaken by the South Norfolk Building Preservation Trust.

THE TRUST’S EVOLVING ROLES

Working in partnerships like the one with South Norfolk Building Preservation Trust at Ketteringham, represents a fruitful avenue for the MMT to explore, and full credit is owed to those other parties who have done the all-important rescue work. The MMT is not able to tackle the conservation demands of many cases, but can perform a helpful role in assuming long-term guardianship of these formerly friendless structures.

Another important form of partnership is with parishes: local care and occasional maintenance lies at the heart of successful management. Another role that the MMT wants to develop further is that of encouraging interest in the genre of funereal architecture. Its highly commended gazetteer, compiled by Teresa and David Sladen, is an exceptional resource: easy to use, fully illustrated and with brief condition surveys, it amply displays the uniqueness, variety and abundance of the mausoleum type. The trust also wants to promote more visits, lectures, and events of interest to its growing band of members.

|

|

| The Wynne Ellis mausoleum, Whitstable, Kent |

CHURCHYARD AND CEMETERY MONUMENTS

The observant reader will have registered that while there are two M’s in MMT, all discussion above has been of mausolea. Why include the word ‘monument’ in the title if this is an area that the MMT has yet to engage with? This is a fair point, and is one that the MMT is beginning to discuss. We lack a national body to champion the cause of churchyard and cemetery monuments, and it is increasingly evident that this is one area of the historic environment that is in persistent and irreversible decline, with only partial signs of rescue in all too few places.

GATHERING STRENGTH AND SUPPORT

The MMT is fortunate to have two distinguished scholars as its patrons: Professor James Stevens Curl and Tim Knox at the Soane Museum, as well as learned and determined trustees. The work of the trust is made possible by the diligence of its secretary, John St Brioc Hooper, and by the financial direction of Ian Johnson. It is supported by a regular newsletter, expertly compiled by Signe Hoffos.

A seemingly infinite amount remains to be done, and the MMT is still a young and fledgling charity. But the trust has already built up a strong reputation as a conservation charity that achieves its projects and it draws great strength from the realisation that it can draw on the enthusiasm of growing ranks of supporters.

As family obligation dies away, others must step up to the mark. Jill Allibone identified a pressing issue and laid down a challenge to all who cherish this often overlooked aspect of our heritage. Readers who would like to help to ensure the survival of an endangered mausoleum can find out how to get involved at the MMT’s website.

Recommended Reading

- Howard Colvin, Architecture and the Afterlife, Yale University Press, London and New Haven, 1991

- James Stevens Curl, A Celebration of Death, Constable, London, 1980

- Sarah Rutherford, The Victorian Cemetery, Shire Library, Oxford, 2008