Mortgage Valuations on Historic Buildings

Stephen Boniface

|

|

|

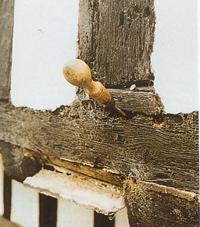

| A timber framed house with panels re-rendered using a hard cement: the panels allow rain to penetrate the walls at their junction with the exposed timbers but restrict its evaporation, causing extensive decay | ||

In recent years many

conservation officers and conservation organisations such as the Society

for the Protection of Ancient Buildings have expressed concern that purchasers

of historic buildings are not being given the best advice by surveyors and

other professionals. In part their concern relates to the advice given in

detailed building surveys, but it also relates to mortgage valuations which

make recommendations that are inappropriate and could ultimately be damaging.

Whether or not a more detailed survey is commissioned, the purchaser relies

on professional advisors to understand the type of property they are dealing

with and to provide appropriate advice. Unfortunately where listed buildings

are concerned, this trust is often misplaced. This is for two reasons. Firstly

those of us in the property professions are not usually taught to deal with

historic structures. Most training courses concentrate on modern buildings

and there is rarely any detailed consideration of those defects and construction

problems which are peculiar to traditional structures. Secondly, many repair

techniques which are still being used are now known to damage traditional

structures, and unless a surveyor has kept abreast of recent developments

in our understanding of historic buildings, his or her advice may be out-of-date

and even damaging.

VALUATION SURVEYS

There are around half a million listed buildings in the UK and millions

more unlisted buildings in almost 10,000 conservation areas. Each year a

proportion of these buildings will be sold subject to a valuation survey,

which is the minimum survey acceptable to banks and building societies for

a mortgage. It is estimated that only 15 per cent of all purchasers opt

for a more detailed survey at the time of purchase, although the proportion

may be slightly higher with historic building purchases.

Surveyors and

valuers undertaking mortgage valuations are guided by what is commonly known

as the 'Red Book' (RICS/ISBA Appraisal and Valuation Manual). This provides

helpful guidance on what valuers should do when faced with a listed or historic

building. However, it is clear that not all surveyors and valuers follow

this guidance, and often they will be unaware whether an historic building

is protected in any way. At present, only a couple of building societies

include a question on their valuation report forms to establish whether

a building is listed or in a conservation area.

The valuation survey needs to be carried out by a suitably qualified professional

who has relevant, up-to-date experience, and who has trained on one of the

specialist post-qualification courses now available to the professions for

the following reasons:

- A value cannot be properly placed on any building unless a basic assessment of the building's condition has been made. To make this assessment the valuer needs to understand the building's construction, the defects which are likely to arise, and, their financial implications.

- Sometimes surveyors and valuers will place a provisional value on the building, subject to further 'specialist' reports. Without a detailed knowledge of the nature of the construction, its probable defects and appropriate solutions, the valuer is unlikely to request the most suitable report and may misunderstand its findings. A non-specialist valuer may accept or even recommend a 'free survey' by 'specialists' who have a vested interest in finding work.

- If the valuer's analysis is incorrect or if the lending institution incorrectly interprets recommendations, inappropriate or even damaging conditions may be imposed on a mortgage offer. There is also the possibility that a building owner will misinterpret the valuer's comments.

- Inappropriate advice may also lead to the employment of a contractor who does not have the appropriate experience and the work itself may therefore be executed poorly or inappropriately.

In England and Wales, each of these potential problems is compounded by

the need for a purchase to be completed as quickly as possible, leaving

little opportunity for survey results and mortgage requirements to be challenged.

In Scotland the situation is improved by the requirement for the survey

to be carried out by the vendor in advance, and alterations to the requirements

south of the Border are being considered.

|

|

|

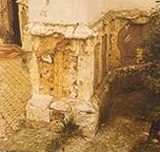

| The crumbling stone walls of a converted church: the walls had been rendered with a hard cement mortar externally and tanked internally, with a solid concrete floor; as a result moisture could only escape through the stone details | ||

INSURANCE

Most mortgage valuations also include an assessment of the 'reinstatement

cost' for insurance purposes (the sum for which the building should be insured).

At present, the only published guidance on the calculation of this cost

relates to buildings constructed around 1900 onwards, and very few mortgage

valuers have a detailed working knowledge of repair and re-building costs

for historic structures or have access to such information. The Royal Institution

of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) is presently working to improve this situation

by providing guidance. In the meantime unless the mortgage valuer concerned

has appropriate specialist knowledge, it would be advisable to have the

insurance reinstatement this cost within a mortgage valuation re-assessed

independently by a specialist.

Some mortgages are directly or indirectly linked to specific insurance policies,

not all of which cater for historic buildings. As soon as some companies

realise that a building is historic or different in some way their premium

is increased because they believe that there is a significant increase in

their risk. However, an increasing number of specialist insurance companies

do understand the risks involved. Provided that the basic insurance reinstatement

cost assessment has been properly undertaken, these companies can provide

competitive rates and are likely to raise fewer problems if a claim has

to be made in the future, due to their specialist knowledge.

SOME COMMON MIS-DIAGNOSES

Dampness

|

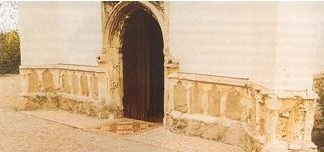

| DETAIL SHOWING THE REMAINS OF A TIMBER FRAME WITH A FLINT PLINTH. The replacement of the floor with a solid concrete slab had forced underlying moisture into the surrounding walls, which acted like wicks causing the sole plate to rot. |

|

| DETAIL SHOWING THE DECAY OF A TIMBER FRAME caused by the introduction of hard cement render and a lead flashing. Both alterations had been designed to prevent the timber frame becoming damp, but in fact had prevented them from drying and therefore had caused the timber to decay. |

The fabric of historic buildings tends to have a higher moisture content

than the fabric of modern buildings because traditional construction techniques

rely on natural evaporation to control damp. The use of a dense 'renovating

plaster' following the injection of a chemical damp-proof course masks the

damp from a moisture meter, so higher than normal moisture meter readings

usually indicate that an old building has not been treated, regardless of

whether there is a the damp 'problem'. Unfortunately, many mortgage valuers

fail to investigate beyond the use of a moisture meter and immediately recommend

a 'specialist damp report'. As this is often carried out by a damp and timber

decay contractor as a free service, rising damp problems are regularly misdiagnosed

and some historic buildings have been needlessly damaged by chemical injections.

Whilst it is imperative that the problem of dampness is not underestimated,

neither should it be misdiagnosed. Dampness is perhaps the single most important

issue and potentially the most damaging problem to an historic building.

Therefore it is most important that it is always properly treated.

Pointing

Masonry walls of stone or brick bedded and pointed in a traditional lime

mortar are often re-pointed with ordinary Portland cement with disastrous

results. In one recent case the re-pointing of a 14th century building was

recommended simply because the mortar was 'soft'. The valuer, who had actually

undertaken a detailed building survey as well, had fundamentally failed

to understand that he was dealing with lime mortar. If the client had followed

the advice to re-point in a cement/sand mix the result could have been quite

devastating.

Structural movement

Almost all historic buildings undergo slight movement throughout their life,

and not all signs of movement indicate ongoing problems: traditional structures

are not as rigid as modern ones and can tolerate a surprising degree of

movement; and cracks may be historic, indicating old movement which ceased

many years ago. However, occasionally movement will be ongoing, so the preliminary

assessment by the valuer once again requires a good understanding of traditional

building construction and how it functions. Misdiagnosis can lead to structural

reports being called for unnecessarily, which wastes the clients' money

and causes further delay. Then there is the added problem that the majority

of structural engineers, like surveyors, are not trained in historic building

defects: employing an engineer without the appropriate experience can lead

to further misdiagnosis, compounding the problem.

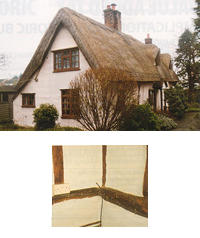

A TIMBER FRAMED THATCHED COTTAGE which had been rendered both externally and internally with a hard and impervious cement render. As a result the underside of the sole plate (the bottom member of the frame) had begun to rot. |

Timber treatment

Many historic buildings have had some form of beetle infestation more or

less since they were constructed. In many instances the infestation will

no longer be active, and misdiagnosis will lead to unnecessary treatment.

It is generally advisable only to use insecticides where active infestation

is present and where it cannot be dealt with by other means.

Replacement joinery

There is a tendency for surveyors to take the easy option in dealing with

necessary repairs by simply recommending replacement of damaged components.

For example, if a small amount of rot is noted in the bottom rail of a sash

window it is rarely necessary to replace the entire window. If the building

is listed the loss of any historic feature (including interior and exterior

features) would constitute a criminal offence unless listed building consent

has been obtained.

Roofs

Many historic buildings can have quite complex roof structures and typical

problems are often missed. On the other hand, inappropriate works are sometimes

recommended: many historic buildings have roof trusses that might be considered

weak by modern-day standards and yet still function satisfactorily.

It is clear that there are many opportunities for problems to be misdiagnosed

or for typical defects to be missed altogether. If faults are missed and

the cost of present repairs and the implication of future maintenance are

not properly understood at the time of purchase, the purchaser may not be

able to afford to maintain the building adequately later on. Conversely,

if faults are diagnosed (correctly or incorrectly), purchasers may face

the imposition of conditions with a mortgage offer. Sometimes these are

simply requirements to undertake certain works within a period of time,

but the lending institution can also retain a proportion of the loan until

certain works are completed to its requirements.

Before accepting any such conditions or 'retentions' the purchaser should

seek specialist advice from a suitably qualified professional.

GUIDANCE TO PURCHASERS

- Choose your mortgage institution carefully: first check that the lending institution offers mortgages on the particular type of property.

- If the lending institution proposes to appoint the valuer, ask for assurance that the valuer will be a specialist who is qualified to advise on historic buildings. If assurance cannot be provided, ask whether the institution would accept a valuation by an independent professional of your own choice.

- Check whether the mortgage is tied to a specific insurance policy, or whether an insurance valuation by an independent professional would be acceptable.

- Do not rely on a mortgage valuation alone. Without a more detailed building survey it is not possible to fully understand the nature of the building you propose to buy, its existing defects, and the type of defects and problems that could arise in future.

- Make sure that the person carrying out the full survey is suitably qualified. He or she should have undertaken specialist training in conservation (such as one of the post-graduate courses), or should otherwise be able to demonstrate current, up-to-date experience in the survey and specification of repair and conservation of listed buildings. Any alteration or repair requirements indicated by a specialist are also more likely to be accepted by conservation officers.

- Surveyors should have a sound working knowledge of the Red Book in order that any advice and recommendations can be set in the context of its guidance. Advice given in this way will be given more weight when being considered by the lending institution.

- Do not appoint companies such as damp-proofing and timber-treatment

contractors to carry out 'free' surveys as they will have a vested interest

in finding problems.

THE FUTURE

With increasing interest in conservation there are signs that the situation

is improving. More people are aware that historic buildings have special

requirements, and more courses are beginning to include the study of historic

building construction and defect analysis.

Within the RICS the Building Conservation Group now numbers around 500 members.

In addition, the RICS operates an accreditation scheme for those who are

particularly experienced or qualified to deal with historic building conservation.

The Conservation Group publishes a journal and organises training days,

and a series of articles is being prepared to appear in the professional

press which specifically addresses the problem of mortgage valuations. Further

amendments are also being made to guidance in the Red Book.