The National Plant Collection Scheme

Ros Johnson and Simon Gulliver

|

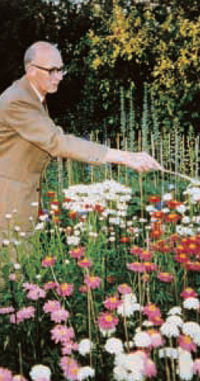

| Collections are maintained in different ways. At Marwood Hill the National Collection of Iris ensata is incorporated into mixed beds in the bog garden and streamside planting (Marwood Hill Gardens); while Gerald Goddard nurtures his collection of Tanacetum (previously known as Pyrethrum) in specialist beds, where they don't have to compete with more rampant growers. (G Goddard) |

Britain and Ireland's wealth of great houses is well known but how often do we consider their magnificent settings - their gardens and parks - as a plant treasure trove of equal value? The owners of great houses, both the landed gentry and the industrial and mercantile nouveau-riche of the Victorian age, were the patrons of British botanists, plantsmen and famous nurserymen of the past. The result of these centuries of study and patronage is an unparalleled assemblage of garden plants that forms the nation's horticultural heritage. But this kaleidoscope of variety (and the unique biodiversity contained within its genes) is under threat. Plants, especially those requiring special care, are transient and need constant attention to ensure their preservation. Every year unique plants are lost from historic gardens, some bred, others collected from the wild, simply because their value is not recognised.

WHAT IS THE NCCPG?

The National Council for the Conservation of Plants and Gardens (NCCPG) was established in 1978 to arrest the decline in the range of plants available to the public. The self-supporting charity consists of a network of 41 local voluntary groups which work actively to promote garden plant conservation, promoting local specialist nurseries and important garden sites. Their fund raising efforts support the work of the charity and the administration of the National Plant Collection® scheme, within which tens of thousands of historically important cultivars and species grow happily for future generations to enjoy. The number and range of plant collections has grown steadily over the past 22 years despite constant funding difficulties, and now consists of approximately 630 collections held on 450 sites, safeguarding approximately 70,000 species and cultivars.

WHO ARE THE NATIONAL COLLECTION HOLDERS?

Collection holders come in all shapes and sizes, including the National Trust, National Trust for Scotland, English Heritage, botanical gardens and arboreta. The Royal Horticultural Society holds a number of collections, as do many horticultural colleges and local authorities. Other guardians include charitable trusts and landowners of historic gardens with significant mature plant collections. Although the proportion of collections held by small specialist nurseries and private individuals is steadily rising, established collections in internationally recognised gardens are still the backbone of the scheme.

|

|

|

| Collection holders are many and varied. The National Collection of Erica is held at United Distilleries' Cherrybank Gardens (NCCPG) while the Burnby Hall Trust curates the Nymphaea Collection at Burnby Hall Gardens. (NCCPG). Sizergh Castle in Cumbria, a National Trust property, is home to collections of Asplenium scolopendrium, Cystopteris, Dryopteris and Osmunda; some of the ferns seen here are planted on a 1920s rock garden. (John Sales) |

WHAT DO THEY DO?

The majority of collection holders protect living material of one plant group such as maples or snowdrops, contributing to the scheme's systematic representation of cultivated plants in the UK. Occasionally collections are based around a prolific plantsman or nursery. Sir Harold Hillier's Gardens and Arboretum holds the collection of plants raised by Hillier Nurseries Ltd. Worthing Borough Council protects a collection of plants selected by the famous plantsman Sir Frederick Stern on the site that was his garden. Collection holders search out old and new plant varieties, ensuring that both modern and heritage strains will be alive and available in the future. They also investigate their plants' growing conditions and research historical and cultural associations.

DUPLICATE COLLECTIONS

A common misunderstanding of the scheme is that there is only one collection in each genus. Collections which are not covered by the scheme are welcomed, however, having multiple collections ensures that all our conservation eggs are not in one basket. Extreme climatic events like hard frosts or storms and disease can severely affect a collection - those in the South remember only too well the 'great storm' of 1987 - and duplicates give potential for restocking from unaffected sites. A geographical spread also enables hardiness to be studied and makes the collections more accessible for the public to view. The Malmaison carnation is a plant that is no longer fashionable, however many estate gardens historically would have had whole greenhouses devoted to it. There are now two National Plant Collections®; one in private ownership in Gloucestershire, the other at Crathes Castle, a National Trust for Scotland property. Both protect the five surviving Malmasion carnation cultivars from extinction.

'FAKE' PLANTS

Collection holders not only protect the plant material, but also work to authenticate the varieties they are protecting. Plants sometimes masquerade under an assumed name as, unlike historic documents or buildings, they are ephemeral, and their propagation is vulnerable to human error. A wrongly labelled seed batch or tray of cuttings can mean a wrongly named plant in the trade. Also, the majority of named cultivars are clones and can only be propagated vegetatively, as seed grown offspring will have different features from their parents. It is not uncommon for a seed grown plant to be distributed under the name of its cultivar parent. When wrongly named plants enter the commercial cycle of propagation and sale, and the changeling predominates, the error can lead to the extinction of the original. It is here that the old collections, particularly of shrubs and trees, supported by historical records can be so valuable in identifying the true plant that was introduced or bred many decades or even centuries ago. Without collection holders' research, record keeping and careful propagation, many more plants would be lost forever.

ORNAMENTAL OR SYSTEMATIC DISPLAY

The visual value of a collection is secondary to its conservation value, and consequently the collections, which must be available for viewing by the public and professionals alike (sometimes by appointment only), are displayed in many ways. Whilst collections distributed in general garden plantings are decoratively valuable, they often make comparisons between plants difficult, hence many collections, particularly herbaceous ones, are held in display beds where close proximity highlights variations between plants. Such collections can be a blaze of colour in season, but are of only academic interest at other times of the year. Collections held by nurseries or plant breeders may not be specifically displayed at all, being held within their stock beds and research fields.

PLANTS THOUGHT TO BE LOST

|

| Papaver orientale 'Charming' is one cultivar that was almost lost, at one time held only by the mother of an NCCPG member in her Wiltshire garden. There is much need to protect these plants, which make up our rich and diverse garden heritage. |

|

| Thought to be lost: the magnificent clove-scented Malmaison carnations were a favourite of the Empress Joséphine, but were superseded by more vigorous strains. Collection Holder Jim Marshall first became aware of these plants over 30 years ago and has since managed to obtain five cultivars. There are now two National Collections of these: Jim Marshall's and one at Crathes Castle, National Trust for Scotland. |

One of the main ways of advertising that a rare plant is being looked for is its inclusion on the Pink Sheet. This is a list of plants that are thought to be lost, though may be found innocently growing in a garden or nursery; the name long since forgotten, its original breeder and owner dead. Leucanthemum x superbum 'Fiona Coghill', a shasta daisy cultivar with an unusual small greenish centre, was thought to exist only as a description until a keen NCCPG supporter, Reg Maxwell, realised that he had a plant in his care. He had received it from Philip Wood, the man responsible for propagating it when it was marketed in the 1960s. Named after the breeder's granddaughter, it is now commercially available once more.

The importance of period plants and the records associated with them cannot be underestimated in our historic gardens. There are literally thousands of irreplaceable plants that are not protected, and every time garden records are thrown away a part of our history is lost. The NCCPG and its Collection Holders are working to preserve this diversity so that historic landscapes and gardens can be faithfully restored, our cultural heritage is retained, and the biodiversity it contains is protected.