New Stone for Old Techniques for Matching Historic Stone Finishes

Jamie Vans

|

|

| Batting by a student from City of Bath College,' the mallet and chisel are of the type used for the work. The open texture of Stoke Ground base bed can be seen (Jamie Vans) |

Stone decay is a common problem which lurks expensively in the background for many congregations particularly if, as is often the case, the rainwater system has not been properly maintained. In some areas of the country the local stone decays very freely when saturated, in a sort of slow motion explosion, losing all coherence and strength, but where it has not been saturated it often survives so well that every mark of the chisel, axe or drag with which it was dressed is still visible.

Unfortunately the workmanship of stonemasons and builders is not always seen to its best advantage where the common task of replacing severely weathered and damaged stones on historic buildings is concerned. No matter how good the intentions of the owners and the architect may be when carrying out repairs, it can be difficult to achieve a style and standard of work which does not in some way mar the appearance of the building. However skilfully it is carried out, the insertion of new stone into a weathered wall is likely to have a substantial impact on its appearance. Indeed, the visible differences between old and new may actually increase with time especially if materials have not been carefully chosen or if stone from a suitable source is not available. Even the most essential improvements such as the provision of an efficient rainwater system may perpetuate and accentuate any differences by preventing the weather reaching the new stone, inhibiting or occasionally increasing the accumulation of dirt, and preventing the growth of lichens. Some disruption to the surrounding fabric is also likely, in the form of damaged arrises, slight movement in the surrounding joints, and holes made to insert the necessary temporary support for the remaining structure.

|

|

|

It is clearly necessary to preserve as much of the original stonework of an old building as possible, and if replacement is unavoidable, new work should normally be kept to a minimum.

Sad to say, not every builder or stonemason is capable of carrying out properly the work in which he claims to be a specialist. It is extraordinary that so often the owners of a building will entrust its care and repair to a complete stranger chosen by competitive tender from a list of other strangers. Taking up references and visiting at least one job of a comparable nature offers no guarantee of quality workmanship but it must be the least that anyone in that situation should do before adding a company name to the tender list.

The fact is that, while it is often easy to see that a repair is unsuccessful, it is not always so simple to specify a method which would have achieved a better result. A number of difficulties stand in the way of anyone trying to write a clear description of, for example, a particular style of chiselled surface. Technical terms are often imprecise: when describing the texture of chisel-marks for example, language is as infuriatingly uncertain as when dealing with colours or flavours. Regional differences in craft teaching and local practice, which are an essential part of the diversity of vernacular building, only add to the difficulty of a specifier attempting to describe what he wants the job to look like.

THE WAY FORWARD

The essential first step before undertaking any stonework repairs is to establish the cause of the problem and to determine whether work is really necessary. The cause of any damage must always be dealt with as the first priority; in some cases, simple improvements to rainwater goods or minor repairs to a protective cornice or string course above an area of damaged stone may make expensive structural repairs unnecessary.

Decisions on which and how much stone to replace inevitably have to be made as work proceeds, largely based on the skill and judgement of the subcontractor. The appointment of stonemasons who are able to interpret the requirements of the building and the professional is therefore vital.

SELECTING A CONTRACTOR

Before work on the Grand Stair repairs at Woodchester Mansion, near Stroud, Gloucestershire was undertaken, members of Woodchester Mansion's fabric committee visited the workshops and a current work site of ten contractors before inviting a short list of six to tender for the contract. Only then could the committee be confident that any of the chosen companies could be relied on to provide workmanship of the right quality in all the relevant trades.

A delegate at a recent COTAC[1] conference described the 'two envelope' system of tendering, according to which each contractor returns his bid in two separate envelopes. The first to be opened contains the names of the key personnel who will be involved in carrying out the work; the second, which is opened only on condition that the first has given satisfaction, contains the figures.

It was also suggested at the conference that both clients and contractors might benefit if it was made clear from the outset that the tender accepted would be not the lowest bid but, for example, the bid closest to the average figure. This would help to ensure that a sensible figure was arrived at, rather than trying to do quality work on the cheap.

It is common practice to build a trial section of walling or to work some exemplar stones to be approved before they are inserted into the building, but even this is far from infallible. Any panels of sample stones will usually have been treated as of great importance and carried out with particular care, often by one of the more experienced and skilled craftsmen available; the main job, the really important bit, may not get the same treatment. Impressive trials are therefore not a guarantee of success, but they will help to eliminate some unsuitable contractors.

Clients should particularly beware of the practice widespread in the stone trade of employing unqualified personnel such as bricklayers for fixing stonework. It is essential that the person who fixes the stone should be a qualified mason; only then will he fully understand the importance of careful handling and accurate bedding and be aware of any details which need adjustment.

Working on site (Figures 4 & 5) is by far the most effective way to achieve an accurate reproduction of all forms of original masonry detail and should be standard practice where a very high degree of replication is required. If this is really not possible, a site visit for masons working on the project is essential to allow them to see what is required of them, and rubbings and photographs may be used to assist back at the workshop. The extra expenses of working in this way may be compensated for by the improved likelihood of achieving correct results first time.

SELECTING YOUR STONE

In some areas such as the Cotswolds, where the stone can vary sharply in character and quality from one small quarry to the next only a few hundred yards away, the matching of stone on historic buildings has become something of a nightmare. In the whole of the Gloucestershire Cotswolds, south of the A40 from Burford to Gloucester, there is no longer any source of dimension stone - that is, stone of sufficient size and quality to be sawn for worked masonry - apart from one heroic company which quarries Tetbury stone. Minchinhampton and Painswick stones, from which Gloucester Cathedral was built, are long gone, as are Leckhampton, Dowdeswell, Stroud, Nailsworth and many others. The stones of the North Cotswolds and from the Bath and Corsham area usually allow the specifier to achieve a reasonable match for colour and texture but the special character of many local materials is lost, probably for ever. On the other hand, the more uniform output of these larger quarries now in production certainly simplifies the choice. Selection of stone is often dictated by availability above all.

For the Grand Stair at Woodchester Mansion it was impossible to achieve a close match from sources currently available in England or France. The stone originally used has a characteristic banding of fine and coarser shelly material which apparently does not occur outside the quarries of the Stroud area. Rather than use another Cotswold stone with a strong but different character, Monks Park was selected for the interior ashlar, which is the finest grained of the Bath stones available. On the exterior, where weathering was a factor, the top bed of Stoke Ground stone was used. In both cases the effect is rather more bland than the stone of the original building and the texture more regular. Availability of stone of sufficient bed height was another factor in this selection.

Centuries ago, quarrymen and masons found that the more shelly and open textured limestones were often more resistant to weathering than fine-grained stones and scientific testing tends to confirm their view. It is, it appears, not so much porosity (air space) in the stone which causes problems but micro-porosity (very small spaces in which water can get trapped). For copings and other weather surfaces, the original builders used a shelly, often crystalline stone of the sort usually referred to locally as Minchinhampton stone. The closest match for this might have been Clipsham but the Stoke Ground base bed, which has a coarser texture than the top bed, will weather in convincingly in a few years.

TECHNIQUES

In the past, when stone was worked by hand from an early stage, the finish was often the end result of the production process itself. Because the mason who made the original tool marks was trying to get rid of the excess stone, he went at it with a will; his tool marks were often bold and deep as a result. Today stone will very often be sawn to size and the finish will be applied by the mason as a sort of distressing of the surface in the belief that he has only to dent the 'perfect' sawn surface to achieve the appearance required -indeed to do more would be considered 'wrong' as his straight edge will tell him. Furthermore, the mason's tool tends to leave only a superficial mark as it skids off the smooth sawn stone. Working from an already flat surface also tends to lead to a uniform and mechanical style of tool marks. In these circumstances it may be that the masons have to be encouraged to relax and to worry less about straight lines and strict accuracy; with practice and a more relaxed hand, a mason will still achieve good results.

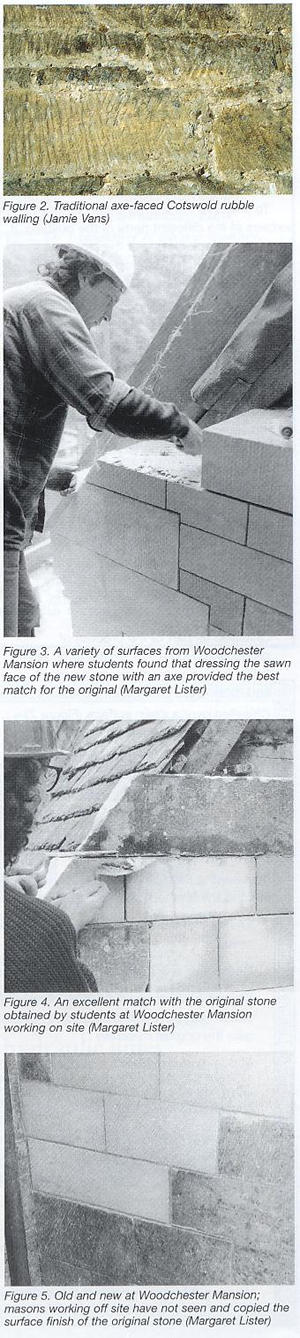

Careful observation of the nature of the surface to be copied is essential if the final result is to be a good match. Chisel and axe marks can usually be distinguished by, for example, the shape of the mark made by the tool. When the heavy Cotswold-style axe is used in the traditional way for stone production, rather than simply dressing the face of a stone, it makes broad, flat marks, unevenly distributed and often radiating slightly as the mason has turned to reach along the stone rather than moving his feet. Beds and joints are cut roughly square with the axe. The result (Figure 2) is a very lively surface which was then normally flush pointed and limewashed to protect it from the weather.

To preserve the characteristic surface textures of the different parts of the building, a mason must look closely at the stones around the work area and to develop a method of matching their character. Observation, experimentation and practice are essential. It may well be necessary to experiment with different tools and techniques, using different chisels, weight of hammer or mallet or sometimes an axe.

The most common stone finishes used on vernacular buildings constructed of limestone fall into seven main categories (although these might or might not be understood by another mason in the same way):

- Axed as part of the process of stone production - marks usually broad, unevenly spaced and varying considerably in direction (Figure 2)

- Axed over a sawn surface (Figure 3), for cosmetic effect only - more regularly spaced marks with a shallow scoop, often with flats between the marks

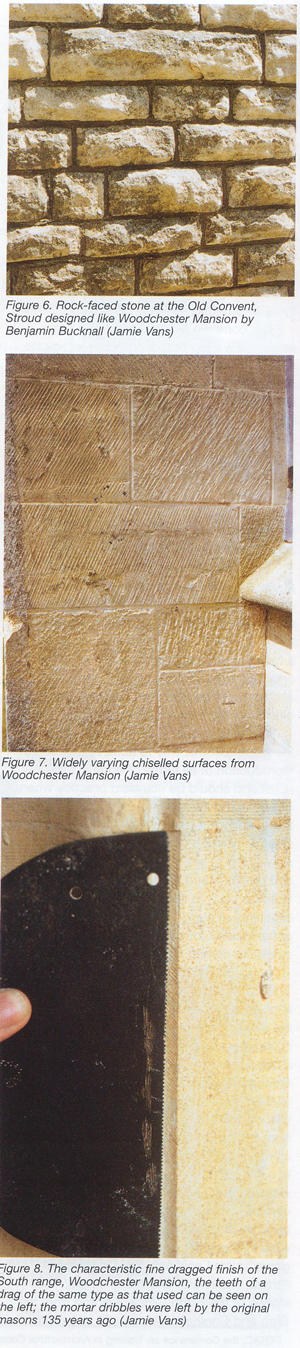

- Chiselled as part of the process of production (Figure 7) - similar to an axed finish, but usually with marks narrower and more regular

- Chiselled over a sawn surface (Figure 7) - often the chisel is driven into the stone rather than taking out a scoop

Special chisel finishes:

- Batted (Illustration at start of article) - regular chisel marks at consistent angles and in straight rows

- Batted margins (around the edge of the stone only; used commonly in Portland but rarely in the Cotswolds)

- Dragged (drags are also known as combs) - often used for dressings with rubble walling and for ashlar (Figure 8)

- Pitch-faced or rock-faced, mostly on 19th century buildings (Figure 6)

- Claw chisel marks are also occasionally seen though these would not normally be considered to be correct (confusingly, claws are also sometimes known as combs).

This list is undoubtedly far from exhaustive, but it may help to draw attention firstly to the variety of finishes which have been commonly used, and secondly to some of the techniques which may be employed to match the works.

| Key Points for Specifiers |

| The following key recommendations may help to bridge the gap between the vision of one man and the finished job of another: |

|