Ornamental Cast Iron

David Mitchell

|

||

| Cast iron railing detail in the grounds of St Magnus Cathedral, Orkney |

Iron ore was traditionally smelted in a blast furnace, originally using charcoal then later coke and coal, although peat was used on a limited basis in some areas. Limestone was added as a flux to reduce the temperature at which the ore melted, and to assist the removal of impurities in the form of slag. The resulting iron was run from the base of the furnace or ‘tapped’ and run into open indentations in the ground known as pig beds for their fanciful resemblance to suckling pigs. The pig iron was manageable by hand and could be re-melted in a small cupola furnace* to make castings.

The castings were originally made in open sand moulds in the ground (sometimes directly from the blast furnace) but, as the industry developed, specialist moulding boxes and moulding sands were introduced. The last remaining architectural iron founders in operation today largely use the same processes as in the 18th and 19th centuries.

The moulder prepared the ‘green sand’, so called because it was used in its raw or ‘green’ state. High quality moulding sand was highly prized, and was largely recycled in the foundry, actually becoming better with use. It contained clay particles among the quartz grains, which were hydrophilic, making it slightly sticky when damp. Fine coal dust was also added throughout the sand, which burned out as the molten metal came into contact with it, helping to take the gases away from the casting and preventing the formation of gas bubbles in the finished product.

|

|

| Casting using a moulding box | |

|

|

| The pig beds at Gartsherrie ironworks in the 1930s, with blast furnace in the background |

A pattern*, usually made of wood, but sometimes of cast iron, lead or plaster, was placed on a board with a box around it, or used as a ‘loose’ pattern (not on a board but resembling the finished casting). The facing sand was finished in plumbago* which was ‘rammed’ or pressed up against the pattern, followed by successive layers of rammed sand. The pattern would then be carefully removed and the process repeated in the other half of the moulding box. When complete, the two sides of the box would be brought together and the molten cast iron taken from the cupola furnace and poured into the mould through pre-formed gates* and risers*. Once cooled, the box would be opened and the casting removed. The excess metal left by the gates and risers would be removed and the casting cleaned up.

Most architectural cast ironwork uses grey iron* for manufacture. Cast irons have varying degrees of ductility*, but all are fairly brittle. Impact resistance is minimal, although the material is excellent in compression and therefore ideal for columns.

THE ORIGINS OF ARCHITECTURAL CAST IRONWORK

Decorative ironwork was largely undertaken in wrought iron until the latter half of the 18th century, when cast iron became increasingly and the demand for mass-production. The evolution of architectural cast ironwork in the 19th century has its stylistic roots firmly embedded in earlier wrought iron forms, and the significant wrought ironwork of smiths such as Jean Tijou in the 17th century had a lasting influence into the 20th century.

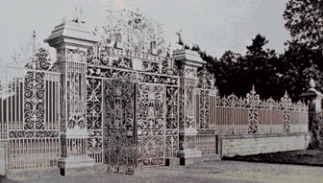

During the first decades of the 18th century, cast iron was increasingly used in component form within wrought iron assemblies, as is the case at Chirk Castle near Llangollen, where the entrance gates and piers by the Roberts brothers erected in 1719 utilised cast iron in the gate pier bases and pediments alone. However, its use as a standalone medium in railings in particular became increasingly important. The earliest significant example of this is generally considered to be the cast iron railings installed around St Paul’s Cathedral in 1714. Cast at Lamberhurst in Kent, the castings weighed 200 tons.

While Sir Christopher Wren disapproved of the use of cast iron to bound his building, the Arts and Crafts architect William Lethaby later praised them highly: ‘I do not see how the railings could have been better. They are heavy and rather blunt as befits the situation and the material of which they are made’. Some of these railings were removed and sold at auction in 1876, but much of the work still survives, and it is a testament to both the design and the material that they remain in excellent condition. As Lethaby suggested, the design and execution of the ironwork at St Paul’s reflects an advanced understanding and appreciation of the material. The construction is massive, perhaps too much so, but the ironwork is assembled and jointed like carpentry; the joints are tight and neat throughout. James Gibbs used cast iron railings of a similar design for the Senate House in Cambridge in around 1722, but unlike those at St Paul’s, here he utilised wrought iron bars inserted between the railings.

Isaac Ware’s architectural treatise A Complete Body of Architecture published in 1756 contains several plates illustrating ironwork in the form of gates and railings. Ware makes comment on the architectural use of cast iron in a decorative context: 'Cast iron is very serviceable to the builder and a vast expense is saved in many cases by using it; in rails and balusters it makes a rich and massy appearance when it has cost very little and when wrought iron, much less substantial, would cost a vast sum'. Indeed, the comparatively low production costs of cast iron compared to the labour intensive costs of wrought iron manufacture are pivotal to the rise of the material in a decorative function.

|

|

||

| Entrance gates to Chirk Castle near Llangollen, 1719 | |||

|

|||

| Cast ironwork at St Pauls Cathedral, 1714 | Castings from patterns by the Haworth Brothers, late 18th century |

COALBROOKDALE AND CARRON

Early castings, which were relatively plain and easier to mould and cast, were replaced by increasingly ornamental and stylised designs as the potential of cast iron was realised at Coalbrookdale and then at Carron, through increasingly fine design and pattern work. This would also have required a development in pattern-making and moulding skills, as exemplified by the work of the Haworth brothers at Carron, brought from London to Scotland by the architects Robert and James Adam.

The rise of the Adam brothers was inextricably linked to the rise of the Carron company and of the Scottish ironfounding trade. Early examples of their work used wrought iron often in conjunction with other metals such as copper and brass, but the influence of cast iron gradually appears in their work towards the end of the 18th century. Details such as decorative cast iron finials, usually to classical motifs, were introduced and used in conjunction with wrought iron railings.

A Scottish example of this can be found at the tomb of James Bruce in Larbert Old Church, where remnants of the original railings enclosing the burial site survive. Erected in around 1786, these railings were delicately forged in wrought iron, intersected by a more substantial wrought iron newel post, and topped with a decorative cast iron urn. They are now badly corroding and delaminating, nevertheless, they provide an excellent illustration of the transition period between wrought and cast iron, as the Adam brothers started to use the mass production benefits of cast iron in the finial detail, while retaining delicacy and craftsmanship in the forged bars and cope rails.

The monument to James Bruce was a large cast iron obelisk, which is itself an early Scottish example of the potential of cast iron as a decorative medium for a striking feature. Unfortunately, it has been moved from its original location adjacent to the graveyard where it sat on a masonry plinth where the family remains lie. It can now be found in the church car park, a less than dignified location for such an important monument.

The Adam family became inextricably linked with Carron in the early 1770s when they became shareholders, with John Adam the most prominent in the affairs of the company. The elegance of their designs was carried over to railings and other architectural work.

The execution of the iron bridge at Coalbrookdale by Abraham Darby and the Coalbrookdale Company in 1779 was a significant datum in the use of cast iron as a construction material and as a decorative medium. However, the decorative work that Coalbrookdale was later to become famous for is not particularly evident on the iron bridge. The central panel was cast in an open mould (there is evidence of porosity in the panel and generally across the bridge components). The iron bridge is important less as a decorative expression in architectural ironwork, than as a pivotal statement in the versatility and use of the material.

|

|

||

| The James Bruce Monument, Larbert Old Kirk, Carron Company, c1780 | Central panel of the iron bridge at Coalbrookdale, Coalbrookdale Company, 1779 |

THE GOLDEN AGE

Significant advances in the technology of smelting and working iron were intertwined with the rise of the material for decorative purposes, its potential so clearly demonstrated by the Adam brothers and Carron in Scotland. The technological advances and natural resources realised in Scotland in the late 17th and early 18th centuries were to create strong foundations for the significant architectural ironfounding industry which was to follow. World-famous names like Walter MacFarlane & Co, Lion Foundry, McDowall Steven & Co and the Sun Foundry of George Smith were established within a 30 mile radius of Glasgow. Coalbrookdale excelled in quality but never matched the range and output of those north of the border.

British firms pre-fabricated cast iron palaces, fountains, bandstands, railway stations and bridges, shipping them to the far reaches of the globe. Specifiers in India or Brazil could order from a stock pattern book, selecting a weathervane or rainwater gutter, a clock tower or urinal. The national output peaked around 1890, although it had really started to accelerate with the drive to improve sanitary facilities starting in the 1850s. While catalogues showed high quality ornamental work, most firms relied on the manufacture of sanitary ware to build their business.

AFTER THE VICTORIANS

The taste for ornamental cast ironwork shifted in the Edwardian period, with most firms responding with more subtle art nouveau stylings. The advent of both wars impacted heavily on the industry, with a loss of customers and skilled labour as foundries shifted towards war work.

The post-war housing boom provided a temporary respite in the manufacture of sanitary ware and baths in particular, but this too was short lived as pressure from overseas imports started to bite. A handful of firms embraced the shift to using cast iron as a constructional medium in building facades, and wonderful examples remain largely unknown in our towns and cities. Selfridges (Oxford Street, London) and Unilever House (Victoria Embankment, London) used large amounts of cast iron, and Burtons the tailors used cast iron extensively in its shop fronts in the post-war period.

After 1950 a series of often acrimonious amalgamations and takeovers alongside a general decline saw the sad demise of a once formidable industry. Some smaller firms did survive and, ironically, saw a resurgence of conservation and restoration work in the 1980s re-instating ironwork removed for the war effort or repairing the profusion of Victorian cast ironwork in our public parks. The resurgence was principally driven by the Heritage Lottery Fund Urban Parks Programme. The handful of surviving firms remains under increasing pressure on various fronts. To retain them we need to use them, and to understand and appreciate the high quality that ornamental cast ironwork can achieve.

~~~

Glossary*

| Cupola furnace | Furnace shaped like a smoke stack |

| Ductility | A metal’s ability to retain its strength when its shape is changed |

| Gate | The point at which the molten metal enters the mould |

| Grey iron | Common type of cast iron in which a high proportion of the carbon is in the form of graphite flakes |

| Pattern | ‘Positive’ original used to produce the desired ‘negative’ cavity form inside the mould into which molten metal will be poured |

| Plumbago | Powdered graphite |

| Riser | Channel in the mould allowing formation of a reservoir of molten metal to compensate for shrinkage as the molten metal solidifies |

Recommended Reading

- A Davey, The Maintenance of Iron Rainwater Goods, Historic Scotland (Inform Guide), 2007

- J Gloag and D Bridgwater, A History of Cast Iron in Architecture, George Allen and Unwin, London, 1948

- R Lister, Decorative Wrought Ironwork in Great Britain, David & Charles, Newton Abbot, 1970

- DS Mitchell, Boundary Ironwork: A Guide to Reinstatement, Historic Scotland (Inform Guide), 2005

- DS Mitchell, ‘Iron Structures in Urban Parks: Conservation and Restoration Challenges’ in Preserve and Play, US National Park Service, 2006

- DS Mitchell, Walter MacFarlane & Co, Historic Scotland, 2009 (forthcoming)

- J Starkie Gardner, English Ironwork of the 17th and 18th Centuries, Batsford, London, 1911

- I Ware, A Complete Body of Architecture, T Osborne and J Shipton, London, 1756