Patent Slating

Terry Hughes

|

|

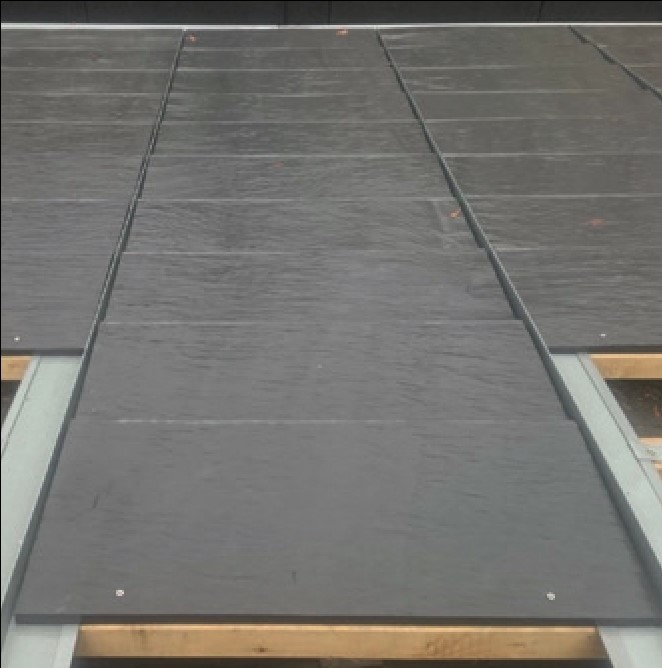

| Fig 1: Rawlinson’s system of patent slating on St George’s Church, Everton. Left: the roof before repair showing a run of slates on the right which have all been cracked, probably by someone walking on them. Right: the same roof during stripping, showing how wide slates were but-jointed over the iron rafters and the gaps oversealed with narrow slates. In the foreground the slabs which form the ceiling can be seen, supported by the iron rafter’s lower flange. (Photos: Terry Hughes) | |

When, in 1772, Charles Rawlinson of Lostwithiel in Cornwall was granted Letters Patent for a New Invented Method of Covering Roofs with Slates he may have believed he had invented something new. No doubt he was unaware that the same system had a long history in Scandinavia, Caithness, Orkney, Ireland and probably many other places. Not only is it a vernacular system but it also came to be re-invented many times after Rawlinson.

THE PATENT SYSTEM

RAWLINSON’S RECIPE FOR UNCTUOUS CEMENT |

A cement for near the sea coasts where the rain penetrates and is driven with great violence. To make a hundred weight, take 66lb of best whiting, 12lb of sea coal or wood ashes sifted very fine, 10lb of hard brick or tile sifted fine, 6lb of white lead; put all into an iron pot, and heat it over the fire, till the moisture is entirely evaporated. Keep it stirring all the time; and when well dried, put to it three quarts of boiled, and six quarts of raw, linseed oil. Mix the above with the hand in a tray, or on a board; then well beat it till it becomes tough and soft; mould it thoroughly with the hand, and examine whether all the parts are well incorporated: if they are, it is fit for use. |

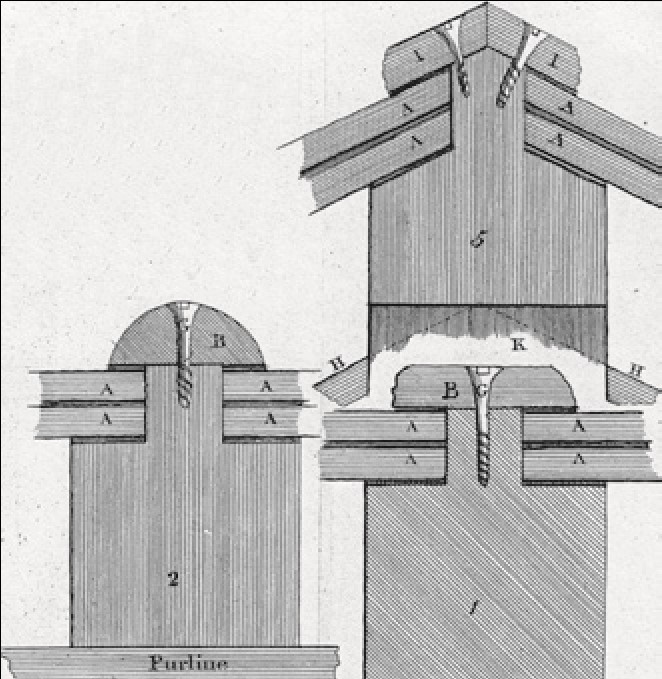

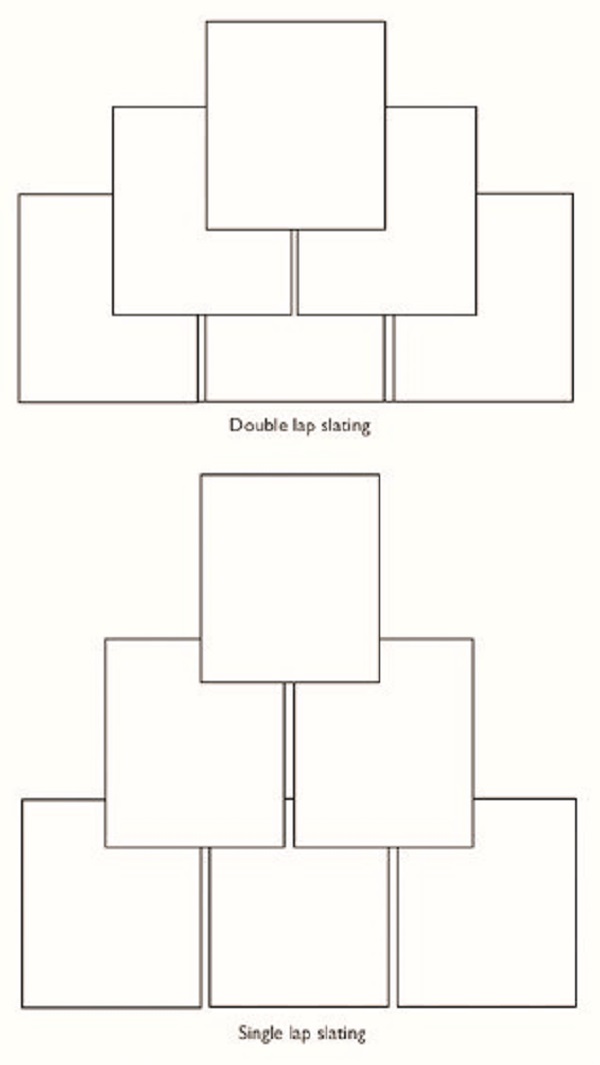

Patent slating is single lapped, so each course of slate only overlaps the course immediately below, like pan tiles (Fig 1). However, single lapped slates do not overlap sideways as pan tiles do, so the perpendicular joints are open and would leak unless they are weathered in some way. Rawlinson chose to do this by bedding narrow slate strips onto the butt joints. This is known today as over-sealing. The alternative is under-sealing (Fig 2). In the more conventional double-lap system of slating the perpendicular joint issue doesn’t arise because each course of slates overlaps the next-but-one course below, so that the overlying course acts as a cover flashing and the underlying one as a soaker (Fig 3).

|

|

| Fig 2: Single-lap slating in Caithness with the vertical joints protected by under-sealing | Fig 5: An example of over-seal slating in Sweden (Photo: Anna Blomberg & Kristina Linscott, Riksantikverieambetet) |

It is interesting to speculate how Rawlinson came to devise his method as he is unlikely to have known about vernacular single-lap slating. He would certainly have known rag slating2 as he refers to ‘slates or rags’ in the patent. This method which is common in Cornwall and Devon uses very large slates of up to 1.3m wide which are nailed directly to rafters without battens. As a result, when fixed in the normal double-lap method they have very large side laps, far wider than necessary. Generally, side laps of no more than 160 mm are needed to prevent leaks in even the most severely exposed situations. As the rags are random sized the actual side lap depends on how the slates are laid together, but even so it would be obvious to any roofer or quarry operator that the width of lap would far exceed what’s necessary. So, wherever large slates or stones were available – from south west England to the far north of Scotland and Scandinavia – single lapping was adopted (Fig 5) and the side gaps were weather-sealed in one way or another.

|

|

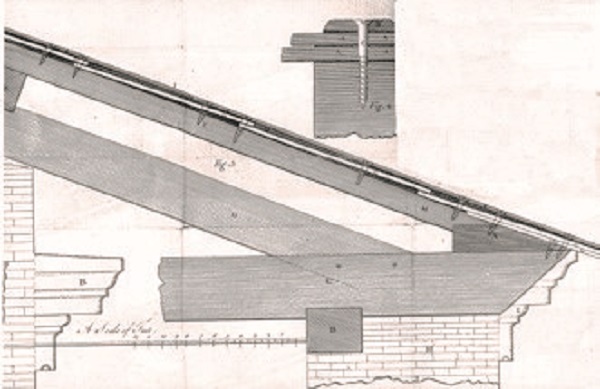

| Fig 4: In Rawlinson’s patent the slates fit into rebated rafters set at centers to fit the slate widths. Later examples simply bedded them on top. | |

Rawlinson slating adopts the same general approach, with rag slates supported between the rafters on either side, into which they were rebated (Fig 4). In practice, the rag slates needed to be available in, or sorted into, sets of equal width sufficient to cover a rafter length, but there could be sets of different widths for each run. Once the widths were known, the rebated rafters were fixed at centres to support the runs of adjacent slates. To seal the butt joints the slates were bedded in ‘unctuous cement’ and screwed to the rafters. Capping slates were bedded and screw-fixed over the perpendicular joints. Rawlinson provided recipes for cement for more and less exposed areas (see box on this page).

HISTORY OF USE

SOME PATENT SLATED ROOFS |

Liverpool churches by Thomas Rickman & John Cragg: St George’s church, Everton, 1813–14, St Michael in the Hamlet church, Aigburth, 1815 St Phillip’s church, Hardman Street, 1815–16 (demolished 1882) London buildings Derby Gate (Formerly Whitehall Club), 47 Parliament St, London, 1864–66, Charles Parnell Reform Club, Pall Mall, London, 1837–41, Charles Barry (roof replaced with clay tiles c2005) Others Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 1841–45, Charles Cockerell Colley House, Reigate, 1840, TR Knowles senior Penoyre House, Nr Brecon, Powys, 1846–48, Anthony Salvin |

As far as is known Rawlinson’s system wasn’t used extensively for roofing in his hometown or in the south-west generally where it is only known (at least to this author) as wall cladding (Fig 6). However, by 1788 patent slates were being made at Penrhyn Quarry in North Wales (as referenced in Welsh Slate by D Gwynn, p44). This was during the time when the Wyatt family of architects was influential in the quarry. Samuel Wyatt was given the job of modernising the medieval hall at the Penrhyn estate and his brother, Benjamin (1745–1818), was appointed general agent to the estate. From this a specific arrangement was established with Lord Penrhyn allowing Samuel and his other brother James (1746–1813) all the slate they required before any was supplied to his Liverpool agents. They promoted many uses for it including patent roofing4. It isn’t known whether Samuel and James Wyatt had seen Rawlinson’s patent or whether the system was invented independently but it was promoted by James and adopted by many architects on buildings in London and further afield (see box on following page) in the first half of the 19th century.

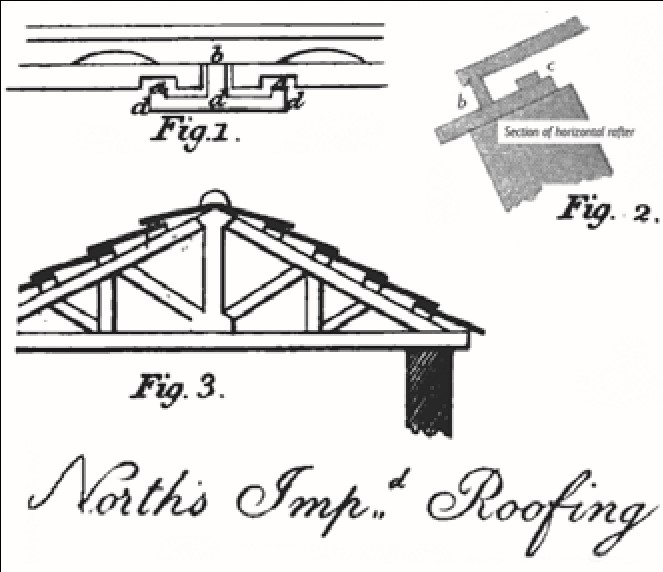

In 1843 another patent was granted to William North which incorporated what today would be called interlocks or water bars made of slate or metal to weather the lateral butt joints rather than using slate rolls. It also included slate or metal strips at the tail of each slate which were ‘scalloped to allow ventilation’ (Fig 7). In a further variation of unknown origin used at Colley House in Reigate, (Fig 8) the slate slabs were not overlapped vertically. Instead they were butt jointed over a slate noggin let into the rafters and sealed with putty. This was still in place in 1999 although the bedding had deteriorated resulting in leaks.

|

| Fig 3: In double-lap slating each course overlaps the next-but-one course below, so the perpendicular joints are weathered. In effect the bottom course acts as a soaker for the middle one, and the top course acts as a cover flashing. In contrast, in single-lap slating the perpendicular joints are open and have to be weathered by over-sealing or under-sealing. |

Rawlinson’s original concept had been for the slates to be screwed to timber rafters positioned to accommodate various widths of slates. However, in Liverpool the ironmaster John Cragg realised that, provided the slate slabs could be made to a specified size, it was ideal as a modular system using cast iron frames. Happily, slate quarries were able to supply 1.5m-wide slates and slabs for the three churches he designed with Thomas Rickman. Two of these, St Michael’s and St George’s have recently been reslated by Finlason Partnership Architects. The third, St Phillip’s in Hardman Street, was demolished in 1882. At St Michael’s the brick walls were also clad with slate fixed behind mouldings in the iron structure and with cramps and spikes. These were almost all removed subsequently, and the brickwork pointed.

CONSERVATION AND REPAIR

Rawlinson predicted that the durability of the timber rafters would determine the life of the roofs. Unfortunately, this wasn’t so: it was the aging and embrittlement of the unctuous cement which eventually led to leaks. More often however, the slating has been assumed to have been the cause when in reality the leaks were the result of other defects. In the Liverpool churches leaks were associated with the structural cast iron gutters which stood on top of the walls. These problems have been repeatedly compounded by people walking on the low pitch roofs to try to locate the assumed leaks in the slating and breaking the slates (Fig 1).

The Penrhyn slates themselves are very durable and can usually be reused provided they are undamaged. However, if it is necessary to lift any of them, this must be done carefully to avoid damaging the fixing holes. If replacements are needed Welsh Slate Limited can supply them.

|

|

| Figure 7: William North’s patent incorporated ‘a fillet of slate, lead or other metal attached to the underside of the slate or slab; which fillet is scalloped on its underside, more or less as may be required, so as to admit air from without to the timbers of the roof and to let steam, heat and damp, escape from within.’ It also included what we would today call an interlock at the lateral butt joints. (From The Repertory of Patent Inventions and Other Discoveries and Improvements in Arts, Manufacture and Agriculture vol III Jan) | Fig 8: Colley House, Reigate. The slates were butt jointed vertically as well as horizontally. The rebated into the rafters. It may be an example of William North’s system. |

Where leaks occur in the body of the slating all that is usually needed to cure them is to lift the cover strips and re-bed them with a more durable seal. This was done successfully at Derby Gate in Whitehall in the 1980s (Fig 7), on St Michael’s in 2006 using Arbomeric MP20 modified polymer, and St George’s in 2016 with Compriband TP600 sealing tape. However, the work on the latter two was complicated by the failure of the cast iron gutters which sat on top of the walls, so water was leaking straight into the wall heads. The slate slabs which formed the ceiling were supported by the lower flange of the I-section cast iron rafters, which simply rested on the inner edge of the cast iron gutter. Any leaks or condensation from the rag slates of the roof (carried by the top flange of the rafters) should therefore have been caught by the slabs and discharged into the gutters. Unfortunately the walls had separated, the gutters had cracked in a few places and the joggle joints had leaked.

To deal with all these defects the gutters were lined with stainless steel and, to increase the shallow upstand of the roof over the gutter, the slating was raised with a new timber structure. This also provided an opportunity to support the slates at closer centres to reduce the chances of them being broken if they were ever walked on.

|

| Fig 6: An example of patent slate cladding in Tavistock (Photo: Richard Jordan) |

A FUTURE FOR THE SYSTEM

Classic patent slating seems to have fallen out of favour by the middle of the 19th century but the urge to devise methods of single-lap slating was undiminished. Many patents for similar single-lap systems were registered in Europe and the USA in the 19th and 20th centuries and some are still being registered today. Modern variations tend to use slate, metal or various sorts of damp-course materials or roofing membranes to weather the perpendicular joints. The latter two are especially ill-conceived as the open butt joints leave the membranes exposed to UV light degradation. One of the latest incarnations uses metal channels rather than cover strips to under-seal the joints (Fig 9).

|

|

| Fig 9: A recent example of under-sealed patent slating in Warsaw seen from the ridge looking down. It uses metal channels to weather the joints. (Photo: Valerijus Shlikas, Skaluneris UAB) | Fig 10: Patent slating can usually be repaired and conserved. This under-sealed roof in Stromness, Orkney was renewed in 2005. |

Where the method is a vernacular style, authentic conservation and repair are precarious at best. Not only are they dependent on supplies of the original large slates or stones being available, but also on people recognising the roofs’ heritage and architectural value. For patent slated listed buildings the future is secure because the slates are readily available from the original quarries and modern joint sealing techniques are well established. Beyond that all that is needed is that once a roof has been repaired it should be inspected periodically without walking directly on the slates.

|

| Fig 11: An original 1860s roof which was repaired using new and reused slates in the 1980s. The main difficulty when re-laying these roofs is removing the slates and cover strips without breaking the fixing holes. |

Recommended reading and references

Charles Rawlinson, The directory for patent slating. Calculated to instruct noblemen, gentlemen ... in the use of the new-invented method of covering the roofs of churches, houses … with slates, etc. London, printed for the patentee at Lostwithiel, 1772 (British Library General Reference Collection 1651/474)

Terry G Hughes, 2016, Slating in South West England, SPAB Regional Technical Advice www.spab.org.uk/advice/technical-advice-notes

David Gwyn, Welsh Slate: Archaeology and History of an Industry, RCAHMW 2015 p44 (quoting DD Pritchard Aspects of the Slate Industry, 1943 and J Lindsey, A History of the North Wales Slate Industry, 1974)

Stone Roofing Association leaflets:

Patent Slating – www.stoneroof.org.uk/historic/HistoricRoofs/Patent_slating.html

St George’s Church Everton – www.stoneroof.org.uk/historic/Historic_Roofs/Everton_2.html