Paving the Way

Hard landscaping in the gardens of 18th century Bath

Jane Root

|

| St James' Square, Bristol: gardeners working in the rear garden, by Pole (c 1806). The gardeners have a broom, basket and roller to maintain the gravel walk. (Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery/Bridgeman Art Library) |

The growing body of literature on the history of gardens contains many references to hard surfaces such as paths and terraces, but there seems to have been little systematic study of historic patterns of use of paving and other surfacing materials. Yet these are clearly highly significant elements in any garden, and it is important to understand the historic language of the materials used not only to identify and conserve what already exists, but also because this understanding can offer valuable lessons for new design. Primary research into the history and conservation of 18th and 19th century town gardens in Bath and Bristol has recently been supplemented by the findings of an extensive study on the history of street surfacing in Bath, and further research in Bristol, Midsomer Norton and Radstock, Somerset. The clear patterns of use of locally available materials which have emerged in this area could certainly be paralleled all over the country.

STONE PAVING

One of the principal surfaces used in both streets and gardens was stone paving. During the early years of the 18th century the predominant paving material in Bath was a local Lias limestone. Although ideal for building work, Bath stone did not wear well under foot and very little of it now survives. After the opening of the Avon Navigation in 1727, the use of Pennant, a hard-wearing sandstone found in the coal measures south and east of Bristol, became economically feasible. This stone was also fissible - that is to say that it could be split, like York stone, to produce large slabs with a relatively even surface. Thereafter Pennant was routinely used for pavements in the centre of the city, although the use of Lias continued in secondary streets. It is not clear when Pennant was first used for paving in Bath gardens, but it was probably around the same time and it is now ubiquitous.

Paving was used in gardens in areas where there was likely to be hard wear, and where a sound surface was important, including areas for sitting out as well as for circulation, generally near or on the approach to the house. In the18th and 19th centuries paving was usually laid in regular rows with fine joints. In 1734, The Builder's Dictionary suggested that paving 'in Streets &c' was normally laid dry on a bed of sand, but the flagstone paths in the excavated 18th century garden at 4 Circus, Bath, were found to have been laid on a bed of grey mortar and clinker. Current best practice is to lay the slabs on a soft bed of 1 : 4 hydrated lime : coarse sand which will accommodate their uneven thickness. The choice of mortar for pointing needs to take into account the colour and texture of the mortars used historically as well as best practice, and in Bath this is achieved with a special dark grey mortar of 1 : 4 hydrated lime : coarse sand obtainable from HJ Chard & Sons, a local builders merchants.

|

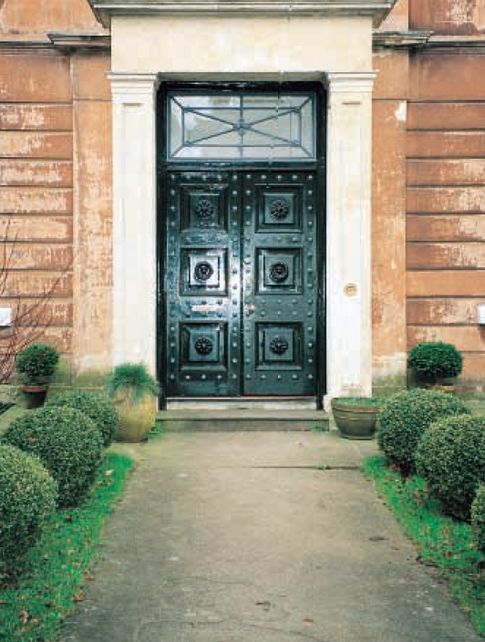

| The front garden path at 6 Woodland Place, Bathwick Hill, of c 1834, made up of four huge slabs of Pennant, is a major element in the design of the approach to the house. |

There are some variations to the usual pattern of paving in Bath. One is the use of exceptionally large slabs which are often found in gateways or forming the front garden path. Front gardens became a feature of new building developments in Bath from the 1790s onwards, and a standard treatment for the approach to the front door seems to have been rapidly adopted. Front garden paths were usually composed of a single line of slabs laid length ways across the path and they sometimes had a border of narrow slips of stone on either side. Paths of this type stand out clearly even where the entire garden is paved, and they continued to be laid in Bath well into the 19th century.

|

| Paving slabs of the local Lias limestone and (in front) the more durable Pennant sandstone at Walcot Reclamation, Bath |

Pennant paving slabs were often roughly tooled in a series of ridges to give a better foothold. This tooled or 'bunched' Pennant was used for pavements on a gradient, for example in College Square in Bristol, but slabs of this type are often found in gardens too. The direction of the tooling sometimes indicates that the slabs have been reused. Steps in Bath are generally simple Pennant monoliths, although Bath stone is also found; it was probably used for steps because it is easier to work. By the early 19th century, steps were sometimes more elaborately detailed, with rounded nosings (the leading edge of a tread), tooled risers (the vertical element at the back of the step) or bunched treads.

GRAVEL

Another predominant material used for hard surfacing in gardens was rolled gravel, although this was not robust enough to be used in streets. Gravel has been used in gardens since Roman times and by the 18th century its use in urban gardens was widespread. There is plenty of evidence for the use of rolled gravel in 18th and early 19th century gardens in Bath and Bristol. One important source is a remarkable series of paintings of the garden of 14 St James's Square, Bristol, dating from the first decade of the 19th century, which are attributed to a member of the Pole family (see opposite) who lived there. The paintings show a gravel walk forming a circuit around this relatively large town garden; they also show areas of paving laid in regular courses near the house and by the back gate, confirming the different situations in which these materials were used.

The garden at 4 Circus was excavated by the Bath Archaeological Trust in 1985, and the original design of c 1760 has subsequently been restored. According to RD Bell, the archaeologist who supervised the excavation, the perimeter path in this garden was paved, but most of the surface, where we would expect to see grass, was found to have been covered with gravel mixed with clay. Contemporary gardening literature recognised the problem posed by high levels of atmospheric pollution in cities and this must have been a factor in the use of gravel in urban gardens (cf Burton 1987, 129-130). In addition, the maintenance needs of gravel were less problematic than those of grass before the invention of the lawnmower in 1830, although even rolled gravel required a fairly intensive regime. For example, in 1806 John Abercrombie instructed that in the 'Flower Garden and Pleasure Ground' during June, gravel walks should 'continue always clean weeded, all litter swept off, and rolled once or twice a week: roll well after rain'. This may explain why, when the garden at 4 Circus was remodelled in 1836-7, the gravelled areas were replaced by lawn.

|

| Bunched Pennant slabs with a border of broken limestone. The direction of the tooling suggests that the Pennants may have been reused. |

|

| A detail of a 'pitched' stone border in Wydcombe, Bath: on the left is the edge of one of the large slabs of Pennant which forms the centre of the path. |

|

| 19th century Pennant steps with tooled risers |

|

| An increasingly rare example of a Victorian terrace garden path laid with fine black and white geometric tiles: clay tiles were reintroduced for garden paths in the 1840s. |

PITCHED PATHS

Another type of surfacing which was commonly used in urban streets in the 18th and 19th centuries was pitching; a 'built' surface of small, more or less regular pieces of stone laid in courses like cobbles or sets on sand or gravel, or later in mortar. In the 18th century, this surface was used for pavements in secondary streets in Bath and Bristol, and it is still found in surrounding villages such as Bathford and Newton St Loe. The pavement around the communal garden in the centre of Moray Place in Edinburgh New Town is also of this type. A pitched pavement was sometimes laid with a single line of flags in the centre, presumably to provide a better surface for pedestrians although this would also have made it easier to wheel a barrow along it. Examples of this type of footway are still occasionally found, for example in an alley off Broad Street, Bath.

No direct evidence of pitched garden paths has been found in the Bath area, but in 1912 Gertrude Jekyll described the traditional use of a particularly decorative type of pitching in an area of West Surrey, which she implies was used for garden paths (Jekyll 1912, 171). A locally occurring 'purplish black' ironstone was found in small regularly shaped pieces which, according to Jekyll "for hundreds of years. have been used by the country people, set on edge, as a 'pitched' paving", often bordered by the indigenous yellow Bargate sandstone, or mixed with it in more elaborate patterns.

LATER DEVELOPMENTS

Local traditions in the use of surfacing materials began to break down in the 19th century. Advances in technology and transport led to the introduction of a range of new street surfacing materials in the middle years of the 19th century, and there were similar developments in gardens too. The introduction of asphalt from France in the late 1830s gave rise to a lively debate in the gardening press about its use for garden paths, and Minton's rediscovery of the process for making encaustic tiles led to their reintroduction in the 1840s (Elliott 1996, 17). In 1912, Gertrude Jekyll recommended the use of novelty materials such as beach shingle in different colours for garden paths, in addition to the more conventional tile and brick. She suggested the use of an interlaced pattern of brick paving found in some Sussex churches, although it is not clear whether this had traditionally been used outside (Jekyll 1912, 177).

A 1926 publication on Garden Architecture took the whole issue of paths very seriously: The Path is one of the biggest problems of the garden. Its width, position and construction are matters of the deepest concern from the first, for the whole layout will be controlled by these most important factors. The garden rests very much on its Paths for required ornamentation. (Henslow 1926, 157) Henslow lists flags, crazy paving, brick, brick dust, cinders, gravel, asphalt and turf as possible materials for paths. Although he does refer to the need to relate the material used to the building materials of the house, this all seems a far cry from the careful evaluation of local tradition which Gertrude Jekyll advocated in 1912: Some of the most interesting methods of paving are those that are peculiar to a district - that grow directly out of the employment of some local product that has stimulated inventive use from past ages.

Bibliography and Recommended Reading

Abercrombie, John The Gardener's Pocket Journal London 1806

Beaton, Mark, Chapman, Mike, Crutchley, Andrew, & Root, Jane Bath Historical Streetscape Survey Vols 1 & 2 unpublished report to Bath & NE Somerset Council 2000

Bell, RD 'The Discovery of a Buried Georgian Garden in Bath' in Garden History Vol 18: No 1, The Garden History Society, Spring 1990

Bristol and Region Archaeological Services & Root, Jane Archaeological and Historical Study of College Square, Bristol BaRAS Report No 600/2000 for Ferguson Mann Architects 2000

Builder's Dictionary, The 2 vols, London 1734 (repr, The Association for Preservation Technology, Washington 1981)

Burton, N 'Georgian Town Gardens' in Traditional Homes October 1987

Chapman, Mike, Root, Jane & Beaton, Mark Radstock and Midsomer Norton Historical Streetscape Survey unpublished report to Bath & NE Somerset Council 2001

Elliott, Brent Victorian Gardens London 1986

Henslow, T & Geoffrey W Garden Architecture: A Pictorial Guide for Gardens Old and New London 1926

Jekyll, Gertrude & Weaver, Lawrence Gardens for Small Country Houses first pub Country Life 1912, repr Antique Collectors' Club 1981

Laird, Mark & Harvey, John H 'The Garden Plan for 13 Upper Gower Street, London: A Conjectural Review of the Planting, Upkeep and Long-Term Maintenance of a Late 18th-Century Town Garden' in Garden History Vol 25: No 2, The Garden History Society, Winter 1997

Longstaffe-Gowan, Todd The London Town Garden 1740-1840 Yale 2001

Glossary

'Bunched' Pennant: A Bath area quarryman's term for Pennant pitching and paving stones tooled in parallel ridges

Lias: West Country name for layered limestone found in the Liassic Series: can be 'Blue' or 'White'

Pennant: Sandstone or grit found in the coal measures, often purple in colour

Pitching: Surface of small stone slips or blocks laid, or 'pitched', on edge