A Taste for the Exotic

Pineapple cultivation in Britain

Johanna Lausen-Higgins

|

|

Flowering ‘Jamaica Queen’ |

Christopher Columbus first encountered the pineapple in 1493, unleashing a flurry of attempts to convey its exotic flavour to uninitiated Europeans. The superlatives and majestic comparisons continued long after. In a work of 1640, John Parkinson, Royal Botanist to Charles I, described the pineapple as:

Scaly like an Artichoke at the first view, but more like to a cone of the Pine tree, which we call a pineapple for the forme... being so sweete in smell... tasting... as if Wine, Rosewater and Sugar were mixed together. (Theatrum Botanicum)

Parkinson wrote those words before the pineapple had even reached the shores of Britain. Its introduction to Europe resulted in a veritable mania for growing pineapples and parading them at the dinner table became a fashion requisite of 18th century nobility. In Britain and the Netherlands the practice was not the preserve of the aristocracy but also extended to the gentry. The pineapple was a representation of owners’ wealth but also a testimony to their gardeners’ skill and experience. Producing a crop of tropical fruit in the colder climes of Europe before the advent of the hot water heating system in 1816 was a remarkable achievement and was, perhaps not unjustly, described as ‘artistry’.

The founding of horticultural societies during the Victorian period brought new opportunities for the display of pineapples at horticultural shows, a tradition that lasted until the beginning of the 20th century. However, the inevitable demise of the pineapple as horticultural status symbol began with the arrival of imported fruit from the Azores at the end of the 19th century.

ORIGIN

Pineapples originate from the Orinoco basin in South America, but before their introduction to Europe, the date of which is uncertain, they were distributed throughout the tropics. Later, this led to some confusion about their origin. The Gardener’s Dictionary of 1759 by Philip Miller, for example, gives the origin of the pineapple as Africa. The pineapple is a terrestrial, tropical plant but is remarkably desiccation-tolerant as it possesses a range of leaf adaptations that help it to cope with drought. This must explain why the plant’s distribution was so successful long before the invention of the Wardian case (the 19th century forerunner of the terrarium).

EARLY HISTORY

European pineapple cultivation was pioneered in the Netherlands. The early success of Dutch growers was a reflection of the trade monopoly the Netherlands enjoyed in the Caribbean in the form of the Dutch West India Company, established in 1621. As a result, plant stock could be imported directly from the West Indies in the form of seeds, suckers and crowns, from which the first plants were propagated.

Agnes Block is believed to be the first person to fruit a pineapple in Europe, on her estate at Vijerhof near Leiden. Many eminent Dutch growers joined the challenge, including Jan Commelin, at the Amsterdam Hortus botanical garden between 1688 and 1689, and Caspar Fagel at his seat De Leeuwenhorst in Noordwijkerhout. Pieter de la Court, a wealthy cloth merchant at Driehoek near Leiden, devised his own system for growing pineapples and many British gardeners were sent to his estate to learn about his cultivation techniques.

Dutch methods of pineapple growing became the blueprint for cultivation in Britain, undoubtedly endorsed after the Glorious Revolution of 1688 cemented Anglo-Dutch relations. William Bentinck, close adviser of William III, is thought to have shipped the entire stock of Caspar Fagel’s pineapple plants over to Hampton Court in 1692. The fruits were, however, ripened from this stock of mature plants and therefore did not count as British-grown pineapples. Pineapples had been ripened in this way before, as commemorated in Hendrik Danckerts’ painting of 1675 depicting Charles II being presented with a pineapple by John Rose, gardener to the Duchess of Cleveland. Danckerts’ painting led to the common misconception that Rose was the first to grow a pineapple in Britain.

|

|

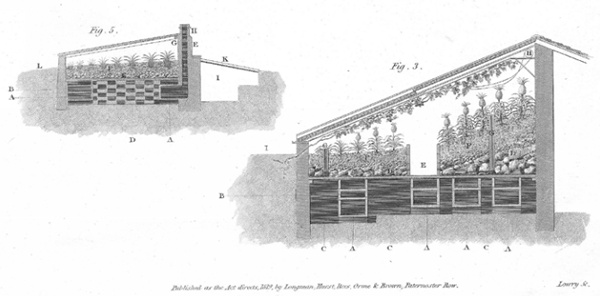

| Illustration of hothouse and pinery-vinery from Loudon’s An Encyclopedia of Gardening |

THE 18TH CENTURY

The first reliable crop of pineapples in Britain was in fact achieved by a Dutch grower, Henry Telende, gardener to Matthew Decker, at his seat in Richmond between 1714 and 1716. Decker commissioned a painting in 1720 to celebrate this feat and this time the pineapple takes pride of place as the sole object of admiration. From this point on the craze for growing them developed into a full-blown pineapple mania. The list of gentlemen engaged in this rarefied horticultural activity reads like a who’s who of Georgian society and includes the poets William Cowper and Alexander Pope and the architect Lord Burlington.

The period is mainly associated with the English landscape movement and glasshouse cultivation is a rather neglected subject. The latter was, however, an important part of 18th century horticulture and many of the associated inventions that we now take for granted were developed or refined during this period, such as the use of angled glazing, spirit thermometers and furnace-heated greenhouses called hothouses or stoves.

STRUCTURES DESIGNED FOR PINEAPPLE GROWING

The appearance of innovations seems to follow no clear chronological order. Early attempts at cultivation were made in orangeries, which had been designed to provide frost protection for citrus fruit during the winter months. Orangeries, however, did not provide enough heat and light for the tropical pineapple, which grew all year round. Heating in glasshouses during the mid 17th century was provided by furnaces placed within the structure, but fumes often damaged or killed the plants. Hot-air flues were then devised, which dissipated heat slowly through winding flues built into cavity walls. These ‘fire walls’ were heated by hot air rising from furnaces or stoves and required constant stoking with coal. This was a dangerous method and many early ‘pineries’, as they later became known, burned down when the inevitable accumulation of soot and debris within the flues caught fire. A light environment with even, fume-free, continuous heat was still only an aspiration.

|

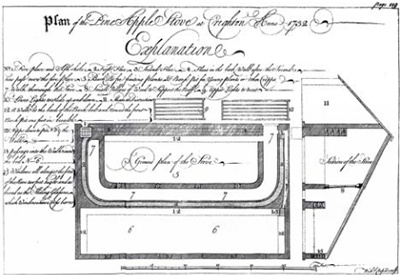

||

| James Justice’s plan of the pineapple stove published in The Scots Gardiners’ Director, 1754 |

Henry Telende’s method of pineapple cultivation was published in Richard Bradley’s A General Treatise of Husbandry and Gardening in 1721. Telende grew the young plants, called ‘succession plants’, in large cold frames called tan pits. The fruiting plants would subsequently be moved into the stove or hothouse to benefit from the additional heat provided by the hot-air flues.

The tan pits were lined with pebbles at the bottom followed by a layer of manure and then topped with a layer of tanners’ bark into which the pots were plunged. The last of these elements was the most important. Tanners’ bark (oak bark soaked in water and used in leather tanning) fermented slowly, steadily producing a constant temperature of 25ºC-30ºC for two to three months and a further two if stirred. Manure alone was inferior, in that it heated violently at first but cooled more quickly. Stable bottom heat is essential for pineapple cultivation and tanners’ bark provided the first reliable source. It became one of the most fundamental resources for hothouse gardeners and remained in use until the end of the 19th century.

James Justice, a principal clerk at the Court of Sessions at Edinburgh, was also a talented amateur gardener. On his estate at Crichton he developed an incredibly efficient glasshouse in which he combined the bark pits for succession and fruiting plants under one roof. (Justice published a very elegant drawing of it in The Scots Gardiners’ Director in 1754.) In a letter to Philip Miller and other members of the Royal Society in 1728, he proudly announces: ‘I have eight of the Ananas in fine fruit’. The letter makes Justice the first documented gardener to have grown pineapples successfully in Scotland, which may be one of the reasons why he was appointed fellow of The Royal Society in 1730. The genus Justicia, named after him, commemorates his horticultural legacy.

|

||

| The extraordinary Pineapple Summerhouse at Dunmore, Scotland was once flanked by hothouses (1761–1776) |

An interesting variant growing structure was the pinery-vinery, first proposed by Thomas Hitt in 1757. Here, vines created a canopy for an understorey of pineapples. The vines would have been planted, as was customary in vineries, outside, and fed into the structure through small open arches built into the low brick wall. A fervent admirer of this method was William Speechly, gardener to the third Duke of Portland, and grandson of William Bentinck, who had sent the first batch of pineapples to Britain in 1692. Portland inherited Welbeck Abbey in Nottinghamshire in 1762, and his passion for growing pineapples nearly ruined him. Nevertheless, he sent Speechly to Holland like many before him to study all the latest techniques.

Speechly published his now greatly refined methods in A Treatise on the Culture of the Pineapple and the Management of the Hot-house in 1779, with a detailed plan of his ‘Approved Pine and Grape Stove’. Overall, however, the structure is very similar to Justice’s earlier design of 1730, and Speechly may have drawn important lessons from it. The profile is virtually identical and he also combined the tanners’ bark pits for young and fruiting plants into one structure, the former at the front, the latter at the back.

The most stunning setting for pineapple hothouses was in the kitchen garden at Dunmore, Scotland, the seat of John Murray, Earl of Dunmore. The roof of the summerhouse, built into the sheltered south-facing wall, is carved into the shape of a giant stone pineapple and still commands the walled orchard today. Its gothic ogee-arched windows terminate cleverly into the midrib of the leaves that curve outward in beautiful arches four feet wide. Above, the leaf-like bracts and plump fruitlets give it an incredibly naturalistic look. The structure is completed with a spiny-leafed crown. To anyone familiar with pineapple varieties it is immediately obvious that the cultivar ‘Jamaica Queen’ must have been used as the model, a variety with fiercely spiny leaves, outward projecting fruitlets and a perfectly egg-shaped outline tapering more towards the top.

Although this outstanding work of art survives, the hothouses which would have flanked it have gone; the chimneys for the flues, beautifully disguised as Grecian urns are now the only evidence that this exotic fruit once flourished here. Astonishingly, both the architect and the date of this extraordinary building are unknown, but it is thought to have been carved by Italian stonemasons due to the fine quality of the work. The portico, a pedimented Venetian arch, was built in 1761 but the stone pineapple roof is thought to have been added later, between 1761 and 1776.

|

|

| ‘Smooth Cayenne’ pineapples fruiting in their clay pots at the Lost Gardens of Heligan, Cornwall | |

|

|

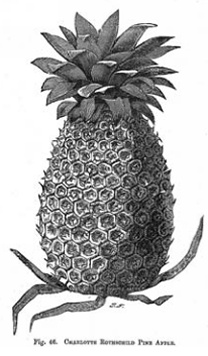

| ‘Charlotte Rothschild’ pineapple illustrated in J Wright’s The Fruit Grower’s Guide Vol V |

Although Philip Miller and John Abercrombie extolled the virtues of tanners’ bark while lamenting the flaws of manure, many structures that used dung as a heating method were devised into the mid 19th century. Adam Taylor wrote a tract titled A Treatise on the Ananas or Pine-apple in 1769 in which the use of horse manure was promoted, probably for the first time, as a method of heating a pineapple pit. The difference here is the use of pits compared to hothouses; pits require less heat to warm the air around the pineapples. Crucially, however, the pots were still plunged into tanners’ bark to provide bottom heat near the plants, with the added bonus of a slightly better odour. The dung was confined to two outer bays flanking the structure, and the fermenting manure released heat, which was conveyed into the structure through pigeon holes. These glasshouses were effectively large cold-frames and this moderate version of a pineapple hothouse meant smaller estates could afford to serve a pineapple at the dinner table. (Pineapples could be hired for dinner parties but cost a guinea each, two if eaten.)

A restored 19th century manure-heated pineapple pit can be seen in action, complete with steaming dung pits and fruiting pines, at the Lost Gardens of Heligan near St Austell in Cornwall. Unfortunately, tanners’ bark can no longer be obtained, making it even more difficult to achieve a healthy crop without the aid of artificial heating. Despite this, large crops were achieved in 1997 and 2002, the latter without the help of tanners’ bark. The first fruit was sent to the Queen, thereby honouring the tradition initiated by Matthew Decker over 250 years ago.

THE 19TH CENTURY

Three developments of the Victorian period changed pineapple cultivation radically: the inventions of hot water heating in 1816 and sheet glass in 1833, and the abolition of the glass tax in 1845. From then on glasshouses for pineapple cultivation became very large and grand structures, with up to 1,000 plants packed into them.

Pineapple cultivation had, by this time, spread widely in Northern Europe to places such as St Petersburg, Paris, Warsaw, Berlin and Munich.

One of the most successful pineapple growers was Joseph Paxton, head gardener to the Duke of Devonshire at Chatsworth between 1826 and 1858. His pineapples were the envy of every estate and regularly won medals at horticultural shows. The pineapple houses at Chatsworth were erected in 1738, but had declined somewhat before Paxton took over. Now quantity as well as size became important, and gardeners were expected to produce fruit all year round; this required a good knowledge of the best winter and summer-fruiting cultivars. If records can be believed, Victorian gardeners grew pineapples of enormous sizes. Cultivation of the pineapple was now the measure of a gardener’s skill and a pinery was mandatory for every estate kitchen garden, and remained so for almost another century.

1900 TO THE PRESENT DAY

Pineapples were still exhibited at horticultural shows in the 1900s but, ironically, just as pineapple cultivation was being perfected, the demand for the home-grown pineapple began to dwindle as imported fruits started to arrive in much better condition than in the past. The first world war eventually put a stop to this horticultural extravaganza. Sadly, of the 52 varieties listed by Monro in 1835, only two remain in cultivation today, ‘Smooth Cayenne’ and ‘Jamaica Queen’. These are thought to be the two major strains from which most cultivars originated.

From the 1950s onwards, pineapples were bred so that they fitted neatly into a tin. Fruits with a characteristically pyramidal shape such as ‘Black Prince’ became extinct. Fortunately, however, some traces of Britain’s long and sometimes eccentric love affair with the pineapple remain. Two working pineapple glasshouses can be seen in Britain today: the 19th century pineapple pit at the Lost Gardens of Heligan, mentioned above, and the pinery-vinery at Tatton Park, which is a recently restored structure dating from the mid 18th century.

~~~

RECOMMENDED READING

- J Abercrombie, The Complete Forcing Gardener, Lockyer Davies, London, 1781

- DP Bartholomew et al (eds), The Pineapple: Botany, Production and Uses, CAB International, Oxon, 2003

- F Beauman, The Pineapple: King of Fruits, Chatto & Windus, London, 2005

- S Campbell, Charleston Kedding: A History of Kitchen Gardening, Ebury Press, London, 1996

- JL Collins, The Pineapple: Botany, Cultivation and Utilization, Leonard Hill Ltd, London, 1960

- G Coppens et al, ‘Germplasm Resources of Pineapple’, J Janick (ed), Horticultural Reviews, Vol 21, 1997

- J Hix, The Glasshouse, Phaidon Press Ltd, London, 1996

- J Lausen-Higgins and P Lusby ‘Pineapple-growing: Its Historical Development and the Cultivation of the Victorian Pineapple Pit at the Lost Gardens of Heligan, Cornwall’, Sibbaldia, No 6, 2008

- JC Loudon, An Encyclopedia of Gardening, Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown & Green, London, 1827

- P Miller, Gardener’s Dictionary, 7th edition, J Rivington, London, 1759

- P Minay, ‘James Justice (16981763): 18th-century Scots Horticulturalist and Botanist – I’, Garden History, Vol 1, No 2, 1973

- WA Speechly, A Treatise on the Culture of the Pineapple and the Management of the Hot-house, A Ward, London, 1779

- M Woods and A Warren, Glass Houses: A History of Greenhouses, Orangeries and Conservatories, Aurum Press, London, 1990

- J Wright, The Fruit Grower’s Guide, JS Virtue & Co Ltd, London, 1892