Restoring the Magic to Law's Close, Kirkcaldy

William Kay

|

To King James VI, Fife was like a 'beggar's mantle fringed with gold': an unproductive land mass bordered by vital coastal burghs along the Firth of Forth. In the late 16th century these small towns and ports were bustling with maritime trade and lucrative industries such as fishing, coal and salt production. Architecturally, one of the highlights of this economic prosperity was the establishment of a class of mercantile house of which Law's Close is probably the finest surviving urban example outside Edinburgh.

Built about 1590 by the Law family of ship-owner/merchants, Law's Close occupies a once strategically important site at the east end of Kirkcaldy High Street opposite the entrance to the harbour, in an area known as Port Brae. For two centuries after its erection the house was owned by powerful local families, including the Coalziers and Boswells, who held sway in the burgh council. However, by the end of the 18th century the house was in decline. The 19th century saw industrialisation push the middle classes further out. The property's fortunes floundered and it was subdivided to provide working-class accommodation with bakery premises below. The townscape was further blighted during the 1930s and 1960s by failed regeneration schemes so that by the mid-1980s the building had been abandoned and was left empty and vulnerable.

Although little was then known about the history of the building, its significance was indicated by its general architectural form, its unusually wide burgage plot, and by the survival of late 17th century decorative plaster ceilings and some panelling. As a direct response to its plight the Scottish Historic Buildings Trust (SHBT) was founded in 1985. Its first project was to acquire and restore this remarkable late 16th century town house, prosaically identified as 'Nos 339-343 High Street, Kirkcaldy'.

|

|

| Restored 17th century panelling on the first floor |

Repair and restoration was directed by Simpson & Brown Architects who assembled a team of specialists to undertake the complex issues involved in understanding and preserving as much historic fabric as possible. Stabilisation of the building was a priority, so phase one was concerned with structural repairs as well as the accumulation of specialist analyses from archaeology to paint investigation.

After so many years of neglect, no one was quite prepared for the regular surprises Law's Close continued to reveal throughout the duration of the project. This is particularly true of its interior decoration which, apart from the intact room at the east end of the first floor, was largely obscured by centuries of overlay.

Archaeological evidence suggests that around 1590 a medieval predecessor was enlarged and recast with a new three-storey ashlar facade. Evidence for the original appearance of the front of the ground storey is more sketchy, but this was possibly at least partly arcaded and may have been used for storage, services or commerce. The intriguing survival of traces of the Kirkcaldy burgh arms painted large in black distemper on original wall plaster in a recess on the east wall suggests commercial use.

When the removal of cement render from the facade exposed the original fenestration pattern, two blocked up window openings were discovered. These had provided light to a stone turnpike stair within the body of the house, just off-centre. The stairway had been removed in the early 19th century when the property was subdivided and a new stairwell tower added at the rear of the property.

There are two distinct phases of decoration: the first of c1590, and a second dates from the refitting of the interiors c1680. In the late 16th century configuration, the plan of the house contained three principal rooms at first floor level consisting of a central hall with large fireplace flanked by two chambers. A similar arrangement applied above. This pattern was established following the discovery of three different patterns of polychrome decoration on the board and beam ceilings to the first floor rooms, hidden behind 17th century plaster ceilings. These tempera paintings, which had been applied directly on to the joists and floorboards of the rooms above, were analysed and photographed in 1990 by Historic Scotland Conservation Centre (HSCC) as part of a wider investigation of the interiors.

In the east room the decoration consisted largely of a geometric pattern on the boards, and floral motifs set out in rectangular panels on the supporting joists.

The ceiling of the central room has a familiar pattern-type of fruit and flowers with beams painted in abstracted foliate devices. This area was partly exposed following removal of a badly damaged plain plaster ceiling revealing charring of the original boards and beams, and is the only expanse to be left on view after cleaning, consolidation and discrete matching in new areas by Sally Cheyne and Owen Davidson of The Conservation Studio, Edinburgh.

In the west-most room the pattern changes again to a scrolling arabesque form in green and pinkish-red on a white ground, with the joists painted similarly to those in the central compartment. The principal beam (visible along with a return moulding of a stone chimneypiece in a later cupboard on the west side) is painted in black and red arabesques within rectangular bordered panels. All of this is fairly typical of the type of decoration found in properties of a similar class and period throughout eastern Scotland.

|

|

|

| Late 16th century polychrome ceiling decoration in tempera on the first floor ceiling (Photo: Simpson and Brown Architects) | Detail of the decoration before ceaning and conservation (Photo: Simpson and Brown Architects) |

Exceptional however, is the discovery at second floor level of a large wall painting in tempera on plaster depicting a late 16th sailing century ship hove-to, with cannon firing below a (damaged) lion rampant figurehead. This wall painting was uncovered accidentally as a consequence of the cutting of a channel in the wall plaster in anticipation of finding a suspected built-up opening. Mercifully, the area of loss missed the hull of the ship, and has been skilfully reconstructed in water-colour, again by Sally Cheyne and Owen Davidson.

It has been postulated that the vessel is of royal status and may represent the ship in which Anne of Denmark paraded the Forth Ports in 1590 following her marriage to James VI. Certainly that union was welcomed by the Scottish mercantile community as it promised expansion of the Baltic trade through Danish-controlled Øresund. As a merchant ship owner William Law might well have wished to celebrate the event.

Other tantalising glimpses of similar wall paintings behind the 17th century panelling suggests that much of the 16th century house was profusely decorated.

|

|

| New tortoiseshell graining and geometric panel decoration in the west room of the second floor accurately reproduces the late 17th century scheme found on the existing panelling (Photo: Tim Hurst) |

About the 1670s or 1680s, changing fashions and perhaps a change of ownership led to an extensive refitting of the interior with timber panelling, moulded cornices and ornate plaster ceilings, and the introduction of sash windows. This necessitated raising the wallhead of the frontage slightly to accommodate additional and enlarged window openings. Overall the tripartite principal room divisions persisted, though on different lines. On the first floor the east room was provided with conventional enough pine panelling, a bolection-profile timber chimneypiece, and a moulded plaster ceiling divided into two compartments by the earlier underlying longitudinal principal beam. The ceiling incorporates devices taken from old moulds in circulation since James VI's last visit to Scotland in 1617.

Paint investigation undertaken by HSCC in 1990 in the panel over the chimneypiece revealed that the panelling had originally been grained to represent walnut and picked out in geometric lines, but had been over-painted with successive coatings of plain colours and, latterly, a heavily varnished wood graining scheme in imitation of oak. The earliest plain treatment of blue in dead-flat oil paint has been reinstated. In the north west corner an area devoid of panelling, but with coeval framing denoted the position for a bed, the traces of fibres and pinholes revealing it had originally been lined with stretched fabric, while fragments of crimson flock paper denoted a mid-18th century treatment.

The central room on this level posed something of a dilemma. The exposed 16th century painted ceiling and large fireplace were at odds with the late 17th century framing which had lost its panels and mouldings when covered with hardboard in the 20th century. The HSCC investigation uncovered the original late 17th century stiles and rails of greenishblack marbling with white veins, while the surviving fixed panels of the window reveals had figured graining contained within a narrow painted border in yellow. Presumably the missing wall panels were similarly treated but, while the original profiles were reinstated, the room was painted a neutral grey with the paint 'scrapes' left on display.

|

|

| New panel decoration in the west room of the second floor (Photo: Tim Hurst) |

The west-most room retained its framing but had also lost its panels, panel mouldings and chair rail, but the profiles were recovered from ghost evidence contained in the paint layers. The north wall of this room was treated differently with wide vertical timber lining boards. Trial removal of overpaint and paper revealed original trompe l'oeil panelling grained in an aqueous medium: contorted swirls of ochre with bright blue marbling represented the framing, and pale grey and re-veined borders were used to simulate the mouldings. At some point a secondary dark greenish-black marbling with white veins was superimposed on the earlier blue scheme. Again, missing timber profiles including those for the door frame and chimneypiece were recovered from the physical evidence of paint margins. An area of exposed decoration was left on the north wall (illustrated above) and the rest of the room reinstated to match by Mike Prior and Mark Nevin in 2005.

A very late discovery in March 2005 changed the complexion of the second floor rooms. Following removal of a confusion of 19th century partitions, the surviving late 17th century pine panelling formed a three-bay open plan arrangement, communicating along the north side. The initial intention was to paint the panelling to accord with early plain colours based on the report by HSCC in 1990, and its update of 2002. The decorator was therefore instructed to strip the panelling of heavy accumulations of paint and paper. Contrary to policy, the operatives used hot air guns in preference to chemical stripping with the result that extraordinary schemes of decoration were uncovered - albeit in a compromised condition. Chemical stripping would have certainly destroyed them without trace. The east room compartment bore traces of highly figured walnut graining, apparently executed directly on to ungrounded (although probably glue-sized) timber; natural pine knots being incorporated into the design. Mouldings were ebonised.

The central compartment was similarly treated, with the added dimension of trompe l'oeil deeply fielded panels. These were profusely and intricately over-grained in a broad interpretation of burr walnut, with ebonised timber mouldings veined with scarlet.

|

|

| Reproducing the late 17th century graining scheme in the west room of the first floor: top left, painting the ground for the graining scheme (Photo: Jonathan Taylor); bottom left, the boarded north wall with its trompe l’oeil paneling (Photo: Simpson and Brown Architects); and right, the room seen from the plainly decorated middle room (Photo: Tim Hurst) |

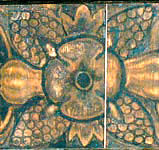

However, the original decorative treatment of the west room panelling proved revelatory. Here the stripping away of over-paint had revealed evidence of a trompe l'oeil scheme of tortoiseshell which, for the 17th century, was exceptionally elaborate and must reflect the status of the owner at this time.

Bristow (1), records faux tortoiseshell in the columns of Wren's altarpiece at Whitehall Palace in 1676 and at Tredegar House in 1688 in combination with grey marbling.

Also in 1688 Stalker and Parker comment: 'House-Painters have of late frequently endeavoured it, for Battens, and Mouldings of Rooms; but I must of necessity say, with such ill success that I have not to the best of my remembrance met with any that have humour'd the Shell so far, as to make it look either natural, or delightful'.

The author of this article was asked to examine and record these interiors with a view to reinstating the west room. Meticulous scale drawings were made at 1:10 delineating every visible brush mark to produce a readily readable document of the decoration. It was felt that the original vestiges were too important to compromise, so that after recording, the panels fields were covered with thin ply to allow reinstatement of the design which recalls furniture inlay designs of the period. The surviving faux tortoiseshell was cleaned and in-painted with distemper to repair damage while new work sought to reproduce the original combination of graining and painted geometry.

On 30 September 2005, the Rt Hon Gordon Brown MP, Chancellor of the Exchequer (in whose constituency Kirkcaldy falls) presided at the opening of Law's Close, marking the completion of a remarkable conservation project that had begun two decades previously.

~~~

(1) Ian C Bristow, Interior House-Painting Colours and Technology 1615-1840, Yale University Press, London, 1996, p139